Number 24 – November 2002

Bail: An Examination of Contemporary Issues

Georgia Brignell, Research Officer

1. Introduction

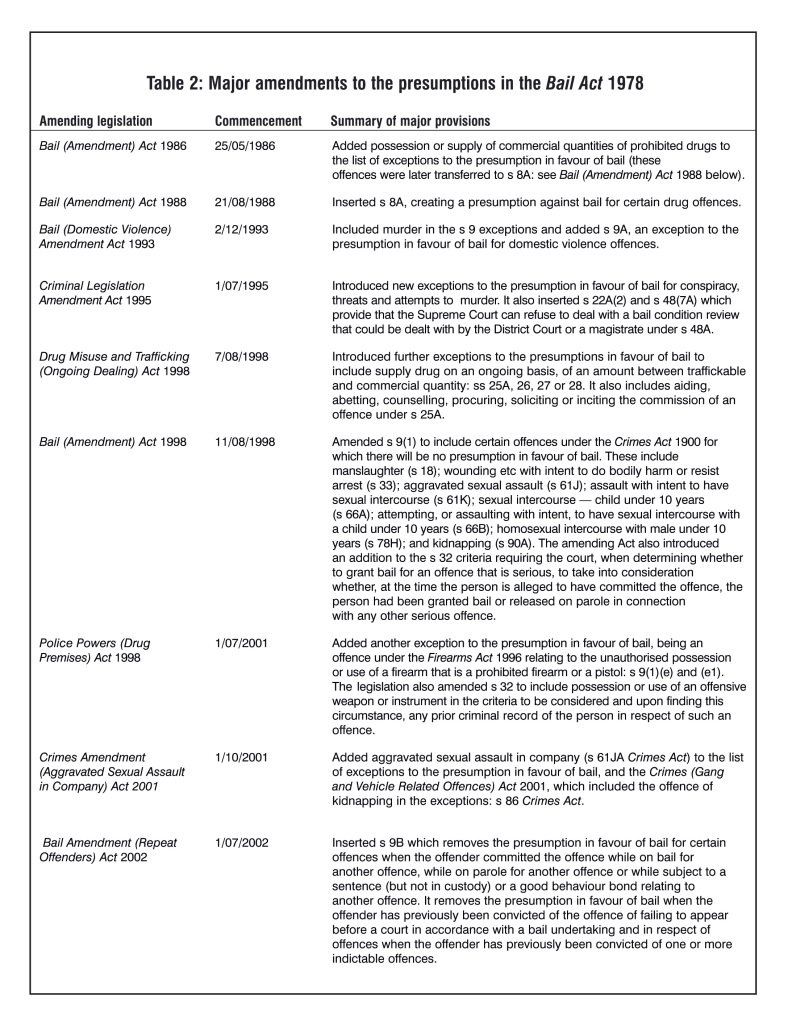

The Bail Act (the Act), introduced in 1978, sought to codify all bail legislation and establish specific criteria for courts when determining bail. In its original form, the Act prescribed a presumption in favour of bail for all but a small number of offences, being the more serious robbery offences.1 Since then, a series of legislative amendments have increased the number of exceptions to the presumption in favour of bail.2

The gradual erosion of the presumption in favour of bail has been the subject of much criticism. It has been argued that this legislative trend has created “a significant potential for anomalies to arise and for any coherent philosophy behind the law of bail to be lost”.3 As far back as 1987, Weatherburn commented “if public opinion no matter how poorly informed, is to become sufficient cause for removing a presumption in favour of bail, the reform engendered by the original Bail Act will disintegrate under the weight of all the exceptions”.4 Indeed if the current trend continues, the presumption in favour of bail may be the exception rather than the rule.

The decision to grant or refuse bail is an extremely important one. Refusal of bail not only seriously infringes an individual’s basic liberty, but also has broader ramifications in the subsequent criminal processing of that individual, such as lack of access to legal and rehabilitation resources.5

Furthermore, bail laws, and decisions based on them, clearly highlight the tension between the competing ideas of the presumption of innocence and protection of the community. An examination of recent bail laws and associated parliamentary debates reveals a shift away from upholding the rights of the individual towards appeasing community fear of violent crime. It is therefore timely to provide an overview of recent changes to NSW bail law and present statistical findings relating to bail. In so doing, this paper considers the underlying assumptions and perspectives on bail, as well as the approach to bail in other jurisdictions.

Legislative reform

The law of bail arose from the provisions in the Statute of Westminster I (1275) which set out categories of persons who were to be refused bail and a category of persons who were not to be refused bail. The Bail Act 1978 (NSW), which commenced on 20 March 1980 and codified the common law, had a similar structure. It was introduced primarily to remedy the inequities underpinning the bail law. Prior to the Act, the granting of bail was heavily dependent on an accused’s financial means, and therefore those with less money were most represented in the unconvicted prison population. The Act was also passed in response to public outcry generated by a case where a bank manager was shot and killed during an armed robbery by a person on bail for prior offences.6

The Act establishes a right to bail for minor offences except for some specified exceptions,7 a presumption in favour of bail for some offences,8 and a presumption against bail for other offences.9 The remaining offences carry a presumption in favour of bail.

The Act also prescribes the criteria to be considered in determining bail.10 Generally, these factors are:

- the probability of the accused person appearing in court

- the interests or needs of the accused person

- the protection of victims or their close relatives

- the protection and welfare of the community.

- Each of these factors list further tests that the court must apply when making the determination. The factors to be considered under s 32 are exclusive, mandatory and exhaustive.11 In R v Hall12 Sully J said:

“SECTION 32 OF THE BAIL ACT IS A LONG, NOT ALTOGETHER HAPPILY EXPRESSED SECTION. PUT SIMPLY, IT ESTABLISHES FOUR CRITERIA TO WHICH A COURT WHICH IS ASKED TO GRANT BAIL, MUST HAVE REGARD. IN RELATION TO EACH OF THOSE CRITERIA THE ACT PROVIDES SPECIFIC TESTS, OR IF YOU LIKE A SUBCRITERIA, BY REFERENCE TO WHICH, ONLY, THE COURT IS TO HAVE REGARD IN ADJUDICATING EACH OF THE FOUR RELEVANT MATTERS…I DO NOT FIND THOSE TESTS EASY TO APPLY AS A MATTER OF CONCEPT, OR AS A MATTER OF PRACTICE…I THINK THAT THE FIRST POINT TO BE GRASPED FIRMLY IS THAT THE ACT IS NOT SPEAKING OF A BARE POSSIBILITY; IT IS SPEAKING OF A CONTINGENCY THAT IS PERCEIVED, IN A RATIONAL WAY AND UPON A RATIONAL BASIS, TO BE MORE PROBABLE THAN NOT.”

The most recent amendments to the Bail Act,13 which remove the presumption in favour of bail for certain repeat offenders, have reignited the bail debate. In his Second Reading Speech,14 the NSW Attorney General, the Honourable Mr Debus MP, stated that the legislation was introduced in response to the growing category of accused persons who repeatedly commit less serious crimes. The increasing incidence of persons failing to appear in court in compliance with their bail conditions was used as evidence of this growing class of offender. The Attorney General emphasised that the existence of a prior offence is only one factor in making that assessment, as the Act requires the court to also consider the type of offence, the seriousness of that offence, the number of prior convictions and the length of time between the offences.

Criticism of recent reform

Much criticism has been made of the new legislation. First, it is argued that the underlying assumption that those who do not appear before court are committing further offences is incorrect. The fact that an offender fails to appear does not necessarily mean he or she deliberately disobeyed the requirement to attend. An offender may not appear for a number of reasons, including forgetting the court attendance date (not an unlikely scenario for many offenders who find their lifestyles characterised by disorganisation) or running late. Furthermore, the statistics,15 which highlighted the increasing incidence of persons failing to attend at their next court date and were a major impetus for the introduction of the legislation, do not record whether an offender appeared the next time or how many offended after failing to attend court.

Second, the legislation16 has been criticised on the basis that it targets the less serious offences, since the Bail Act already covers serious ones. This creates a risk that offenders who fit the class of persons targeted by the legislation may plead guilty, notwithstanding their innocence, if the crime is one which would be likely to attract only a fine or bond, in order to avoid spending time in custody.

Third, it has been suggested that the legislation will result in increased pressure on courts and legal aid duty solicitors, as there will be far more prisoners in custody at the beginning of the day, each individual defendant’s prior record will need to be analysed carefully, and instructions will need to be taken in custody.

Fourth, many of the accused refused bail because of the legislation will suffer great disruption to their family and their jobs, and possibly face dismissal since they will be unable to attend to work commitments.17 Of course, many of these people will not even be convicted at the end of the process.

Underlying assumptions and issues

Presumption of innocence versus protection

of the community

As there is no legal mandate for pre-trial punishment, a bail application can, at a theoretical level, be reduced to an assessment between the competing interests of the accused (who is presumed innocent until proven guilty and entitled to remain at liberty) on the one hand, and the community (which expects to be protected from “dangerous” offenders) on the other. However, any realistic assessment of bail needs to work on the basis that the presumption of innocence must give way, in certain circumstances, to accommodate the community’s interest in having guilt determined (which is facilitated by the accused’s attendance at court) and protecting society against further harm from the offender. It is important that judicial officers and police bear these broader theoretical constructs underpinning the bail system in mind when they are making decisions concerning bail.18

Recently commentators have argued that:19

“…THE NSW BAIL ACT IS CURRENTLY IN GROSS VIOLATION OF INTERNATIONAL LAW, BREACHING CERTAIN SECTIONS OF THE INTERNATIONAL COVENANT ON CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS, TO WHICH AUSTRALIA IS A SIGNATORY. BASICALLY, IT VIOLATES THE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE AND BREACHES THE PRINCIPLE THAT REFUSAL OF BAIL SHOULD BE THE EXCEPTION. IT IS ARGUED THAT CATEGORICALLY DENYING PEOPLE BAIL EQUATES WITH SUBSTANTIAL PRE-TRIAL PUNISHMENT. IT IS AN INJUSTICE THAT AFFRONTS HUMAN DIGNITY, OFFENDS FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES OF LAW AND IS ALL TOO OFTEN FATAL IN ITS CONSEQUENCES.”

In support of these claims, figures show that remand prisoner suicides are disproportionately high, accounting for 36% of suicides among the entire prison population.20

The common law does not sanction preventative detention, that is, punishment that exceeds the penalty commensurate with the seriousness of the offence. Generally, the sentence should relate to the proven offence and not involve speculation about what the offender may do in the future.21 As bail laws, however, particularly the recent amendments to the Bail Act, appear to focus on preventative detention, it is of interest to refer to the judicial outcomes for those who are refused bail. For instance, research into remand inmates in NSW found that 56% of remand inmates received into NSW correctional centres during March 1999 were discharged without a custodial sentence, 41% were given custodial sentences and 3% were still on remand after a year.22

In R v Roberts and Lardner,23 a District Court judge revoked bail when the two defendants arrived late to court after having travelled long distances. Bail was not opposed at the time by the Crown, there was an explanation for the late arrival and there was a presumption in favour of bail for the offences with which they were charged. The alleged offenders had been on bail without incident for three years and, if refused, they would have had trouble communicating with their legal advisers. There was also no evidence that they were unlikely to appear in court for trial if granted bail.

On an application for bail to the NSW Court of Appeal, the court granted bail and held that “it is…vitally important that the court should remind itself that the decision to grant or refuse bail…must not be exercised with a punitive intent”.24

Disadvantages where bail is refused

The issue of disadvantage to those refused bail was considered in Chau v Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth)25 where the defendant challenged the constitutional validity of the Bail Act 1978 on a number of bases, including a claim that it breached the constitutional guarantee of fair process in criminal proceedings. In other words, it was submitted that the absence of bail led to an unfair trial. The NSW Court of Criminal Appeal, disposing of this argument, held that refusal of bail does not automatically lead to an unfair trial. Kirby P said:26

“THERE ARE COUNTLESS EXAMPLES OF TRIALS BEING CONDUCTED WITH PERFECT FAIRNESS ALTHOUGH AN ACCUSED HAS NOT BEEN GRANTED BAIL. THE IMPACT OF A BAIL APPLICATION, WHATEVER ITS OUTCOME, ON THE CONDUCT OF THE TRIAL IS MINIMAL.”

Gleeson CJ added the observation that under the common law there is no right to bail.

Notwithstanding these comments, the disadvantages experienced by those on remand compared to their counterparts at liberty have been well documented.27 Not only do those on remand have fewer resources to prepare their defence, they may make a less favourable impression when they appear in court (they will probably be less well dressed and have experienced a loss of morale). They also miss the opportunity to impress the court by showing that they have met their bail conditions and appeared in court. The accused on remand will have limited opportunities for rehabilitation, will endure upset to their family life, and will suffer stigmatisation and possible contamination by contact with criminals. Furthermore, judicial officers may feel obliged to justify pre-trial custody by guiding the outcome of the trial towards a guilty verdict.28

It has been argued that detaining accused persons before trial is an important means by which the prosecution can procure a guilty plea.29 Kellough and Wortley have found that those persons not held in pre-trial custody are much more likely to have all their charges withdrawn by the prosecution.30 Such findings are, in part, supported by studies which have shown that, controlling for factors such as charge and criminal record, those remanded to custody are much more likely to be convicted and sentenced to prison than those who have been released prior to trial.31 Furthermore, research in Australia has consistently shown a relationship between refusal of bail and negative court outcome, when controlling for the effects of offence seriousness, legal representation, previous convictions and plea.32

Kellough and Wortley also cite research which indicates that in Canadian courts, after controlling for various legal factors, black accused were much more likely to be remanded to custody than offenders from other racial backgrounds, suggesting that personal identity characteristics play a significant part in decisions regarding bail.

Such observations are consistent with the findings of the Aboriginal Justice Advisory Council (AJAC) which indicate that Aboriginal offenders are less likely to have their bail dispensed with, and more likely to have their bail refused.33 The AJAC also found that 11% of Aboriginal defendants who are refused bail are either found not guilty or have their case dismissed, and 45% of Aboriginal remandees do not receive a custodial sentence when their matters are finalised.

The negative impact on those refused bail may be eased through improvements to the amenities in remand (to assist in trial preparation), compensation to those in custody if subsequently acquitted, and speedier trials.34Although some inroads have been made toward redressing the documented discriminatory practices and impact of bail decisions upon certain minority groups,35 the practical effect of these protective measures has yet to be seen.

The concept of risk

Despite the increasing number of exceptions to the presumption in favour of bail, much still rests on the court’s ability to identify potentially dangerous offenders for the purpose of pre-conviction detention. Inherent in all bail decisions is the capacity of the court to discern the level of risk the offender poses. In Veen v The Queen (No 1)36 Stephen J said: “Predictions as to further violence, even when based upon extensive clinical investigation by teams of experienced psychiatrists, have recently been condemned as prone to very significant degrees of error when matched against actuality.”

If one is to acknowledge the maxim of “innocent until proven guilty”, restrictions on pre-trial liberty must be justified on the basis of risk: risk that the accused will fail to appear for court, risk that they will endanger the community and, on a broader ground, the risk that a wrong decision will undermine confidence in the proper administration of justice. Risk assessment is a controversial issue: the accuracy of predictions have been called into question on numerous occasions and, as such, the area is fertile ground for debate. Contributing to that debate is a body of research that found:

n only a small number of defendants commit violent or dangerous offences while on bail

n the amount of crime committed by those on bail is a very small proportion of all crime that is committed

n the longer the time spent on bail, the more likely a defendant is to commit an offence the amount of pre-trial crime could be reduced if the delay in going to trial was reduced.37

The concept of risk is one of the fundamental assumptions underlying the most recent amendments to the bail legislation. In his second reading speech for the Bail Amendment (Repeat Offenders) Bill, the Attorney General suggested:38

“IT IS A COMMON MAXIM THAT PAST BEHAVIOUR IS A GOOD PREDICTOR OF FUTURE BEHAVIOUR. CRIMINAL JUSTICE AGENCIES USE THE EXISTENCE OF PRIOR OFFENCES AS PART OF THEIR CRITERIA IN ASSESSING HIGH-RISK OFFENDERS.”

The rationale behind these recent legislative amendments would appear to support Kellough and Wortley39 who have identified a philosophical shift from the “disciplinary society” that emerged during the nineteenth century to a movement called “new penology”, which is primarily concerned with the principle of risk management. Similarly they suggest that criminal justice policies have moved from focusing on the individual towards assessing and redistributing risk “according to mathematical formulae based largely on past experience.”

Statistical research

Absconding

Although limited research has been done into the characteristics of persons who have been granted bail or the rate at which persons granted bail fail to appear, a paper by the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research40provides some useful statistical information. The paper found that since 1995, the rate of bail refusal has increased and persons with prior convictions are far more likely to have a warrant issued against them for failing to appear while on bail. It also found that in the Local Courts, persons charged with theft offences (receiving, break enter and steal) and disorderly conduct offences are more likely to fail to appear while on bail, whereas in the higher courts, persons charged with serious drug offences or burglary are more likely to fail to appear. The statistics also show that during 2000, 14.6% of those granted bail in the Local Court failed to appear and a warrant was issued.41

These figures, at first glance, would appear to support the recent legislative amendments regarding repeat offenders. However, although the statistics measure how many people released on bail do not appear in court at the appointed time, the data cannot measure how many offenders who were refused bail would have appeared had they been granted bail. The introduction of the Bail (Repeat Offenders) Act 2002 suggests that 14.6% is not an acceptable level of non-compliance. Others42 have suggested that the current absconding rate is reasonable, emphasising that this indicates that 85% of offenders granted bail did in fact appear in court in accordance with their bail undertaking. Ultimately, determining the acceptable breach rate is a political issue.

Bailee offenders v remandee convictions

A worthwhile statistical comparison would be between those who commit offences while on bail and the conviction rate of the remand population in NSW. As indicated before, the AJAC has found that almost half of all Indigenous people detained after being refused bail in NSW do not receive a custodial sentence when their case is finalised in court.43

Padfield44 looks at similar statistics in England, which reveal that 10-12% of offenders commit offences while on bail, compared to an acquittal rate of those remanded in custody of approximately 20%. A further 20% of those refused bail ultimately receive community sentences, and another 20% of men receive a fine, discharge or other non-custodial sentence. Only 41% of men and 26% of women who are in remand receive a custodial sentence. Padfield queries whether “pre-trial custody should concentrate on incarcerating the dangerous, or whether it should give priority to remanding in custody those who are thought likely to abscond”.45

Impact on remand population

In 2001, the average time on remand in Australia was 4.5 months, with 10% of remandees spending more than 10.3 months in custody.46 It is therefore not surprising that commentators have expressed concern about the erosion of the presumption in favour of bail and noted the rapid rise in the remand population.47 For example, in response to the tightening of bail for drug offences, Weatherburn has commented that:48

“…WHILE A WEAKENING OF THE PRESUMPTION IN FAVOUR OF BAIL MAY BE EXPECTED TO DO LITTLE OR NOTHING TO REDUCE THE RATE OF ABSCONDING, IT MAY DO MUCH TO INCREASE THE PROBLEMS OF PRISON OVERCROWDING.”

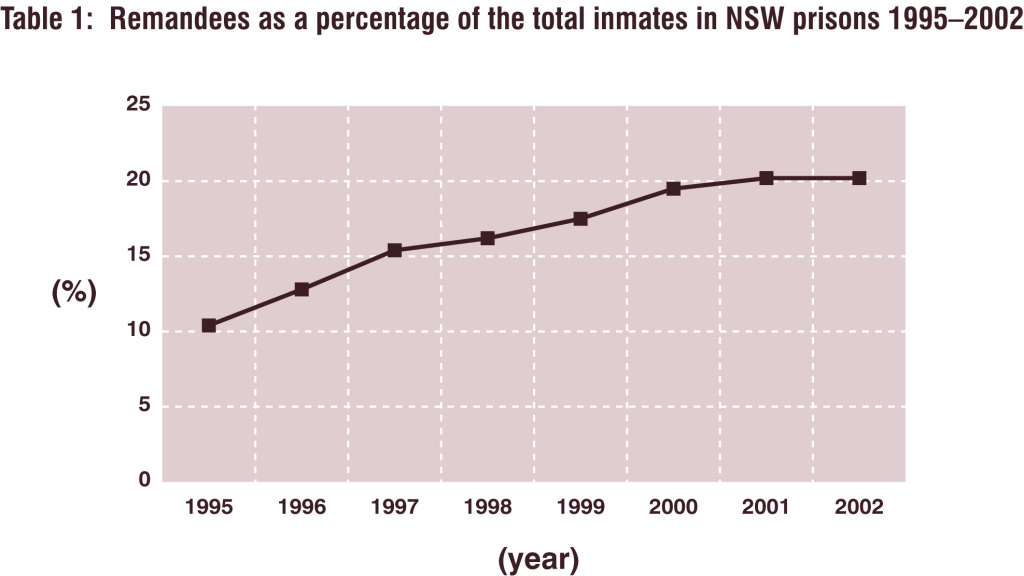

These observations would seem to be supported by statistics showing an increase in the percentage of persons on remand in prison over the past seven years,49 as shown in Table 1.

Although the statistics reveal a significant rise in the number of prisoners on remand, tighter bail laws may not be primarily responsible, as many other factors may also have contributed to the rise in the remand population. These factors have been discussed in the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research’s paper “Increases in the NSW remand population”.50 In that paper, it is suggested that the increasing number of people refused bail may be a result of a general increase in the number of persons appearing in NSW courts, the fact that persons are appearing in greater numbers for offences with high bail refusal rates, such as robbery and break and enter, and the fact that magistrates themselves are less willing to grant bail. Weatherburn51 suggests that the tighter bail laws could have a ripple effect and create a climate of doubt for offences not prescribed as exceptions in the Act, and that judicial officers will be prompted to follow suit in the exercise of their discretion.

Central to this issue is whether the legislative tightening of bail is making an actual difference in the number of accused who are refused bail, or is merely cosmetic. Although it is beyond the scope of this paper, it would be interesting to examine specific offences where legislation has been passed removing the presumption in favour of bail, to determine whether there has been a resulting increase in the proportion of bail-refused cases and a rise in the remand population.

It is too early at this stage to assess whether the recent bail amendments will result in an increase in the number of instances where bail is refused for those offenders meeting the legislative criteria (repeat offenders).

Relevant case law

When examining the operation of the Bail Act it is useful to look at the case law that has developed in relation to particular sections.

Presumption against bail for certain drug offences

The threshold criteria for granting bail under s 8A of the Bail Act has been set high it requires “a real or certain chance of acquittal” before bail is granted. When s 8A applies, an application for bail should ordinarily be refused and a heavy burden rests on the applicant to satisfy the court that bail should be granted.52 The strength of the Crown case is the prime, but not the exclusive consideration, and countervailing circumstances common to applications for bail (set out in s 32 of the Act) are accorded less weight than in the ordinary case. The application must be exceptional if the Crown case is strong.

In R v Kissner,53 Hunt CJ at CL said in regard to s 8A:

“ITS EFFECT IS NOT MERELY TO PLACE AN ONUS UPON THE APPLICANT TO ESTABLISH HIS ENTITLEMENT TO BAIL. HE MUST SATISFY THE COURT THAT BAIL SHOULD NOT BE REFUSED… THE PRESUMPTION EXPRESSES A CLEAR LEGISLATIVE INTENTION THAT PERSONS CHARGED WITH THE SERIOUS DRUG OFFENCES SPECIFIED IN THE SECTION SHOULD NORMALLY OR ORDINARILY BE REFUSED BAIL…”

This interpretation and application of s 8A of the Bail Act has been the subject of recent judicial criticism. Sperling J has remarked on numerous occasions his dissatisfaction with the line of authorities on s 8A but acknowledged that a judge at first instance was bound by them.54 Adams J has also commented55 that Kissner and the authorities following it have developed a gloss on s 8A in using the strength of the Crown case as a primary factor to be considered and that the focus should remain on all criteria outlined in s 32.

Refusal of bail on a prior occasion

When bail has been refused by the Supreme Court on a prior occasion, the accused must also show that special circumstances exist before the court will entertain a further application for bail.56 In R v Bubev,57 the court indicated that the fact that the applicant was in protective custody could be a special circumstance under s 22A on an appeal. The fact that bail has been refused previously is also taken into account by the court in determining the application.

When an appeal against a refusal to grant bail is made to the Court of Appeal, it has been held that the court should exercise restraint in reviewing the refusal as the original judge is in a better position to assess the relevant factors.58 The Court of Appeal has original jurisdiction to consider the s 32 criteria and the jurisdiction does not depend on a demonstrable error by the judge who granted or refused bail. Unlike the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal does not need to find “special circumstances” before it can entertain an application for the revocation of bail.59

Appeal pending

If there is a conviction or sentence appeal pending in the Court of Criminal Appeal, s 30AA requires special or exceptional circumstances to justify the granting of bail. Special circumstances may include the fact that the whole of the sentence will have been served before the appeal is determined,60 if the ground of appeal is certain to succeed,61 or administrative delay in providing court records for the purposes of appeal.62 Establishing special circumstances is, of itself, not enough to justify bail. The offender must then meet the criteria outlined in s 32.

R v Sinanovic63 dealt with an application for bail when an application for special leave to the High Court was pending. There, Justice Greg James referred to R v Velevski64 and said that the test in s 30AA was the same as the common law test applied by the High Court in determining bail applications, that is, whether special or exceptional circumstances exist. Justice Greg James said:65

“THOSE WORDS PERMIT MANY MATTERS TO BE CONSIDERED IN AN INDIVIDUAL CASE. WHAT IS SPECIAL OR EXCEPTIONAL WILL, OF COURSE, BY THE VERY NATURE OF THE CONCEPT INVOLVED IN THOSE WORDS, VARY FROM CASE TO CASE. BUT IT IS CONVENIENT TO LOOK TO CRITERIA ADOPTED BY THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN VELEVSKI AND DERIVED FROM THE APPROACH OF CALLINAN J IN MAROTTA V THE QUEEN.66 THERE CALLINAN J IDENTIFIED 13 FACTORS WHICH HE CONSIDERED AS APPLICABLE TO THAT CASE AS LIKELY TO DISCLOSE WHETHER, IN COMBINATION OR INDIVIDUALLY, THERE WERE SPECIAL OR EXCEPTIONAL CIRCUMSTANCES.”67

In R v Wilson68 it was held that bail will not be granted pending an appeal unless the applicant can establish “something more than an arguable appeal point” and be “most likely to succeed.” In R v LL Smith69 and R v Olivier,70the Court of Criminal Appeal put the test even higher, requiring a ground of appeal “which is certain to succeed” and one “which can be seen without detailed argument to be certain to succeed.”

In Marotta v The Queen,71 however, Callinan J enunciated a lower threshold:

“…WITHOUT IN ANY WAY SEEKING TO PRE-JUDGE THE APPEALS, I AM OF THE VIEW THAT THEY RAISE AN ARGUABLE POINT, WHICH MAY HAVE REAL SUBSTANCE AND WHICH, IF IT SUCCEEDS, WOULD PROBABLY JUSTIFY A RETRIAL.”

Marotta was considered in R v Velevski72 but there was no suggestion that the principles stated in Wilson, Olivier and LL Smith required reconsideration.

Loopholes?

As a result of the piecemeal reform of the Bail Act, bail law has become increasingly complex and provides fertile ground for loopholes. Such a loophole was identified in Whan v McConaghy.73 In that case, the respondent obtained a windfall by having his sentence run from the date he was originally sentenced, even though for much of that sentence he was on bail pending the hearing of an appeal. The High Court held that the grant of bail did not have the effect of a stay of the order of sentence, but had run its course by the time the Court of Appeal purported to set a new date for its commencement. By the time the appeal was heard, the sentence had effectively been served despite the fact that the appellant was on bail. Brennan J said:74

“THE GRANT OF BAIL IN THE PRESENT CASE EFFECTIVELY CANCELLED THE SENTENCE AND ALLOWED THE APPLICANT TO ‘ESCAPE FROM PUNISHMENT AND LAUGH AT JUSTICE’… IF THE PROCESSES OF THE COURT WERE ABUSED BY THE SEEKING OF BAIL, THE SUPPRESSION OF THE ABUSE LAY IN REFUSING BAIL OR, PERHAPS, IN REVOKING THE BAIL ONCE GRANTED. IF THE SEEKING OF BAIL IN THE PRESENT CASE WERE AN ABUSE, IT WAS NOT TO BE REMEDIED BY IMPOSING WHAT IS IN TRUTH A NEW SENTENCE. THE COURT OF APPEAL HAD NO JURISDICTION, EITHER INHERENT OR STATUTORY, TO MAKE THE ORDER UNDER APPEAL.”

The joint judgment went on to state:75

“A SENTENCE OF IMPRISONMENT, LIKE ANY OTHER ORDER, MUST OPERATE IN ACCORDANCE WITH ITS TERMS AS INTERPRETED IN THE CONTEXT OF ANY STATUTORY PROVISION PURSUANT TO WHICH IT IS IMPOSED OR FRAMED …THE FACT THAT THE APPLICANT DID NOT ACTUALLY COMMENCE TO SERVE THE SENTENCE OF IMPRISONMENT DID NOT, IN ITSELF, PREVENT THE TERM OF THE SENTENCE FROM COMMENCING TO RUN.”

In R v Nunan,76 the applicant was sentenced to a fixed term of imprisonment for 10 weeks for two drug offences. She was granted bail by the Supreme Court on the assumption that she had lodged an appeal. Subsequently, it was discovered that no appeal had been lodged and the applicant surrendered herself. The applicant submitted that the original sentence had then expired. The Court of Criminal Appeal held that the sentence began to run from the date specified by the District Court, and accordingly the term had expired. The court, dealing with s 18(3) of the Criminal Appeal Act 1912,77 held:78

“IN THE CASE NOW BEFORE THE COURT THERE WAS NO APPEAL OF ANY CHARACTER TO THIS COURT, LET ALONE ONE THAT WAS ‘DULY INSTITUTED’…PURPOSE OR INTENTION IS NOT SUFFICIENT TO ANSWER THE STATUTORY DESCRIPTION IN THE WORDS OF S 18(2) ‘LIBERTY ON BAIL (PENDING THE DETERMINATION OF HIS OR HER APPEAL)’…

IN MY VIEW THE ABSENCE OF AN APPEAL TO THIS COURT PREVENTS THE STATUTORY DESCRIPTION WITHIN S 18(2) BEING SATISFIED ON THE FACTS OF THIS CASE, FOR THE SAME REASONS THAT THE HIGH COURT IN WHAN V MCCONAGHY CONCLUDED IN THAT CASE, WITH RESPECT TO THE PERIODIC DETENTION OF PRISONERS ACT THERE UNDER CONSIDERATION. IN MY OPINION, S 8 OF THE SENTENCING ACT IS TO THE SAME EFFECT. TIME CONTINUED TO RUN UNDER THE SENTENCES ORIGINALLY IMPOSED BY HER HONOUR.”

In contrast, in R v Carrion79 the respondent was sentenced to periodic detention, but was granted bail pending an appeal to the Court of Criminal Appeal. He did not attend the periodic detention pending the appeal and no order was made staying the execution of the sentence during that period. The NSW Court of Criminal Appeal distinguished Whan v McConaghy and held that the respondent was not taken to have been serving his sentence for periodic detention while he was on bail, and the sentence was extended by the period for which the respondent was at large.

The international perspective

In assessing the NSW bail system, it is useful to have regard to some international approaches to bail procedures and the grounds for rebutting the presumption in favour of bail. Under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms the accused has the right “not to be denied reasonable bail without just cause”.80 Under the Bail Reform Act 1971 (Canada), the onus rests upon the Crown and pre-trial detention is determined at a “show cause hearing”.

The Canadian Criminal Code specifies two grounds for detaining an accused in custody prior to trial.81 The principal ground for refusing bail is that detention is necessary to secure the attendance of the accused at trial. The second ground (which is only determined after detention is found not to be justified on the first ground) is that detention is necessary in the public interest for the protection or safety of the public.82 The difficult task the courts must undertake is the reconciliation of the Charter and the legislation.

The English approach is more reflective of the NSW system.83 The Bail Act 1976 (UK) prescribes three grounds for rebutting the presumption in favour of bail based on the grounds that if bail were granted the offender would either fail to surrender to custody; commit an offence while on bail; or interfere with witnesses or otherwise obstruct the course of justice, whether in relation to himself or any other persons. It is interesting to note that theCriminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 (UK) amended the Bail Act to provide that any defendant charged with or convicted of homicide or rape after a previous conviction of such an offence shall not be granted bail.

In a recent article, Henderson84 examined the English experience in regard to bail and concludes that “information” is the key to ensuring that wrong decisions are kept to a minimum. He makes the point that access to reliable and accurate information is crucial for decision makers so they can tailor their decisions appropriately and minimise error, ensuring that only those accused whom it was necessary to keep in custody, were denied bail. He suggests that training in risk assessment would also be of great value.

In contrast to NSW, New Zealand has taken a more liberal approach in recent years.85 Zindel contends that this is a desirable trend having regard to the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990. Section 24(b) of this Act provides that everyone charged with an offence shall be released on reasonable terms and conditions unless there is just cause for continued detention. Furthermore, s 25(c) reinforces the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty according to the law. The sections have the effect of placing upon the Crown the onus of proof as to why bail should not be granted.

Although no specific statute deals with bail,86 recent case law reflects a movement away from very restrictive principles. Many factors are to be considered when determining whether to grant bail, including:

- the probability or otherwise of the defendant answering to his or her bail and attending the trial87

- the public interest88

- whether there will be a delay in the trial process89

- the risk of re-offending90

- the seriousness of the offence91

- the likelihood of conviction92

Although amendments to the Crimes Act 1961 (NZ)93 have made it more difficult for an offender to receive bail in regard to violent and sexual offences, the courts have specifically indicated that bail principles do not act unfavourably in relation to drug offences.94

Conclusion

Since the Bail Act was first introduced, there have been persistent calls for restricting the availability of bail. As a result, the Act has been altered in a piecemeal fashion characterised by the gradual erosion of the presumption of innocence. It would seem that many amendments have been a result of political imperatives or moral outrage over a particularly abhorrent high profile case, rather than responses to detailed empirical research or evidence. It is questionable whether the current bail law provides a systematic and comprehensive framework, and there would seem to be much to commend the “back to basics” approach such as that found in Canadian law.

Apart from the impact on the presumption of innocence, the past decade of bail law reform has raised other important issues which, in this brief paper, have not been examined in the depth they deserve. However, hopefully the paper has highlighted the fundamental principles and assumptions underlying bail decisions that should be borne in mind by courts in the exercise of discretion.

It is timely to repeat the words of the Honourable Mr Dowd MP, Attorney General, in his Second Reading Speech,95 where he said:

“…IT IS IMPORTANT TO BEAR IN MIND THAT WHAT WE ARE DEALING WITH IS AN ALLEGED CRIME BY AN UNCONVICTED PERSON. THE RIGHT TO LIBERTY IS ONE OF THE MOST FUNDAMENTAL AND TREASURED CONCEPTS IN OUR SOCIETY AND CANNOT BE DISMISSED LIGHTLY. UNDER THE BAIL ACT THERE IS A PRESUMPTION IN FAVOUR OF BAIL FOR MOST OFFENCES. THIS IS CONSISTENT WITH THE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE, WHICH IS A FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLE OF CRIMINAL LAW.”

Endnotes

1 Crimes Act 1900 (NSW), ss 95, 96, 97 and 98.

2 A table of major amendments to the Bail Act is provided at Table 2 on page 8.

3 Criminal Law Review Division, Review of the Bail Act Issues Paper, 1992, Attorney General’s Department, Sydney, p 1.

4 D Weatherburn, M Quinn and G Rich, “Drug charges, bail decisions and absconding” (1987) 20 Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 95 at 108.

5 Julie Stubbs, “Bail or remand” (1991) 16 (6) Legal Services Bulletin 304 and K S Anderson and S Armstrong, Report of the Bail Review Committee, 1977, NSW Government Printer, Sydney.

6 Anderson and Armstrong, op cit n 5.

7 Section 8.

8 Section 9 subject to certain exceptions; see also s 9A for the exception from the presumption in favour of bail for certain domestic violence offences and s 9B for repeat offenders.

9 Section 8A.

10 Section 32.

11 See R v Hilton (1987) 7 NSWLR 745 at 748 and 751; followed in Wilson v The Queen (1994) 34 NSWLR 1.

12 (unrep, 16/1/97, NSW Sup Ct).

13 Bail Amendment (Repeat Offenders) Act 2002 (NSW). The legislation removes the presumption in favour of bail for accused persons: who are charged with other crimes while on bail; who are charged with other crimes while on bonds or parole or on community release; or who have been convicted of a previous fail to appear offence in accordance with a bail undertaking. It also removes the presumption in favour of bail for any person accused of an indictable offence if the person has been convicted of one or more indictable offences: see s 9B.

14 NSW Parliamentary Debates, Hansard, Legislative Assembly, 20 March 2002, p 818.

15 The statistics were derived from M Chilvers et al, “Bail in NSW: characteristics and compliance” (2001) Crime and Justice Statistics Bureau Brief, Issues Paper 15, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Sydney.

16 Bail Amendment (Repeat Offenders) Act 2002 (NSW).

17 Trevor Nyman, “Repeat offenders” (2002) 40(8) Law Society Journal 50.

18 Justice Adams, “Bail”, paper delivered to the Local Courts of NSW 2002 Annual Conference, 1 August 2002.

19 Justice Action media release on bail laws: “More jail no bail Carr overturns the presumption of innocence”, 22 March 2002.

20 Ibid.

21 Veen v The Queen (No 1) (1979) 143 CLR 458 at 467, 468, 482-483, 495; Veen v The Queen (No 2) (1988) 164 CLR 465 at 472-474, 485-486; Chester v The Queen (1988) 165 CLR 611; and G Caine, “The denial of bail for preventive purposes” (1977) 10 (1) Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 27.

22 B Thompson, “Remand inmates in NSW Some statistics”, 2001, Research Bulletin No 20, NSW Department of Corrective Services.

23 (1997) 97 A Crim R 456.

24 Ibid at 459 per Mason P.

25 (1995) 37 NSWLR 639.

26 Ibid at 655.

27 For example, Caine, op cit n 21, and the Quebec Court of Appeal in Pearson (1990) 79 CR (3d) 90.

28 Pearson (1990) 79 CR (3d) 90, cited in S Zindel, “A principled approach to bail” (1993) February New Zealand Law Journal 49 at 51; see also Nyman, op cit n 17.

29 G Kellough and S Wortley, “Remand for plea” (2002) 42 British Journal of Criminology 186.

30 Ibid at 186.

31 Ibid at 187; see also in New Zealand, P Oxley, Remand and Bail Decisions in a Magistrates Court, 1979, Research Series No 7, Research Unit, Planning and Development Division, Department of Justice, Wellington, New Zealand.

32 J Stubbs, “Review of the operation of the NSW Bail Act 1978” in M Finlay, S Egger and J Sutton, Issues in Criminal Justice Administration, 1983, Allen and Unwin.

33 Aboriginal People and Bail Courts in NSW, 2002, Aboriginal Justice Advisory Council, Sydney. The report made a series of recommendations. It recounts a case where a 55 year old Aboriginal woman was arrested for the first time and charged with malicious damage for throwing a shoe at her husband, which broke a window in their rented house. After spending several months on remand waiting for her case to be heard, the charge was dismissed. The findings also indicated that magistrates imposed financial sureties of up to $5,000 as part of bail conditions in over 90% of cases in one court, where more than half the Aborigines in that location have an income of under $300 a week and almost a third get less than $150 a week. In one instance, a surety for a 17 year old boy was imposed for a charge of offensive language.

34 Caine, op cit n 21 at 36.

35 Such as those amendments in the Bail Amendment (Repeat Offenders) Act 2002 which inserted s 32(1)(b)(v) and (vi) into the Bail Act, requiring the courts to consider the special needs of a person who is mentally ill or intellectually disabled when determining a bail application, and implemented the first recommendation of the AJAC report, to remove reliance on employment and residence in assessing a person’s community ties, and to include reference to traditional Aboriginal extended family and kinship ties and traditional ties to place.

36 (1979) 143 CLR 458 at 464.

37 Caine, op cit n 21 at 31.

38 The Honourable Mr Bob Debus MP, Attorney General, NSW Parliamentary Debates, Hansard, Legislative Assembly, 20 March 2002, p 819.

39 Op cit n 29.

40 M Chilvers, J Allen and P Doak, “Absconding on bail” (2002) 68 Crime and Justice Bulletin, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Sydney.

41 Caution needs to be taken when relying on these statistics, as the Bureau does not collect data on all matters coming before the courts.

42 Adams, op cit n 18.

43 Op cit n 33.

44 N Padfield, “Bailing and sentencing the dangerous” in N Walker, Dangerous People, 1996, Blackstone Press, London, p 70.

45 Ibid, p 75.

46 Australian Bureau of Statistics, Corrective Services, Australia, June 2001, No 4512.0.

47 v Weatherburn et al, op cit n 4 at 108.

48 Ibid.

49 Note: Remand prisoners include unconvicted prisoners awaiting a court hearing or trial, and convicted prisoners awaiting sentencing. It excludes those awaiting deportation or extradition. The total inmate figures exclude periodic detainees. The figures are based on the NSW Inmate Census figures provided by the NSW Department of Corrective Services.

50 J Fitzgerald, “Increases in the NSW remand population” (2000) Crime and Justice Statistics, Bureau Brief.

51 Weatherburn et al, op cit n 4 at 108.

52 R v Budiman (1997) 97 A Crim R 548.

53 (unrep, 17/1/92, NSW Sup Ct); Kissner was affirmed in R v Brown (unrep, 15/3/94, NSW CA).

54 R v Iskandar [2001] NSWSC 7 at [6]; see also comments by Sperling J in R v Lu Lu [2002] NSWSC 14 at [3] and R v Cain (No 1) [2001] NSWSC 116, where the offender was granted bail despite a strong Crown case because of other factors such as his age. In Cain Sperling J said (at [9]): “as to the interests of the applicant, he has a legitimate claim to be at liberty to go about a lawful life and to be with his family pending trial…The prospect that a private citizen who has not been convicted of an offence might be imprisoned for as long as two years pending trial is, absent exceptional circumstances, not consistent with modern concepts of civil rights.”

55 Adams, op cit n 18.

56 Bail Act 1978, s 22A; the phrase “special circumstances” was discussed in O’Hare v DPP [2000] NSWSC 430.

57 (unrep, 17/7/98, NSW Sup Ct).

58 R v Budiman (1997) 97 A Crim R 548.

59 Ibid.

60 R v Claxton [1999] NSWSC 653.

61 Ibid.

62 R v Greenham (1998) 103 A Crim R 185.

63 [2001] NSWSC 164.

64 (2000) 117 A Crim R 30.

65 R v Sinanovic [2001] NSWSC 164 at [19].

66 (1999) 73 ALJR 265 at 267.

67 In R v Velevski (2000) 117 A Crim R 30, the NSW CCA also referred to the factors outlined by Callinan J in Marotta.

68 (1994) 34 NSWLR 1.

69 (unrep, 18/5/93, NSW CCA).

70 (unrep, 15/9/93, NSW CCA).

71 (1998) 73 ALJR 265 at [18].

72 (2000) 117 A Crim R 30.

73 (1984) 153 CLR 631.

74 Ibid at 642.

75 Ibid at 635-636.

76 (1999) 108 A Crim R 1.

77 Section 18(3) provides that the time during which the appellant is at liberty on bail (pending the determination of his or her appeal) does not count as part of any term of imprisonment.

78 (1999) 108 A Crim R 1 at [27].

79 [2002] NSWCCA 21.

80 Section 11(e).

81 Section 515(10).

82 Section 515(1).

83 Bail Act 1976 (UK), Schedule 1, Part 1.

84 P Henderson, “Bail: What can be learned from the UK experience?” www.csc-scc.gc.ca/text/forum/bprisons/ english/enge.html (4 July 2002).

85 Zindel, op cit n 28.

86 Apart from ss 318, 319 of the Crimes Act 1900; see Zindel, op cit n 28.

87 Hubbard v Police [1986] 2 NZLR 738.

88 Ibid.

89 James v Police (1986) 2 CRNZ 54.

90 R v Benfield [1980] 2 NZLR 754.

91 R v Barker (1987) 3 CRNZ 83 (although seriousness of itself is not by itself a ground to refuse bail: Cole v Police (1986) 2 CZNZ 52).

92 Police v Hanigan (1990) 6 CRNZ 497.

93 These amendments were made in 1991.

94 Op cit n 28 at 52.

95 NSW Parliamentary Debates, Hansard, Legislative Assembly, 25 May 1988, p 551.

ISSN 1036 4722

Published by the Judicial Commission of New South Wales

| Location: | Level 5, 301 George St, Sydney NSW 2000, Australia |

| Postal address: | GPO Box 3634, Sydney NSW 2001 |

| Telephone: | 02 9299 4421 |

| Fax: | 02 9290 3194 |

| Email: | judcom@judcom.nsw.gov.au |

| Website: | www.judcom.nsw.gov.au |

Disclaimer

This paper was prepared by officers of the Judicial Commission for the information of the Commission and for the information of judicial officers. The views expressed in the report do not necessarily reflect the views of the Judicial Commission itself but only the views of the officers of the Commission who prepared this report for the Commission.