Patrizia Poletti

Principal Research Officer, Statistics

Hugh Donnelly

Director, Research and Sentencing

Pauline Buckland

Editor

Introduction

Since 1989, NSW has had a unique statutory rule which provides that the balance of the term of a sentence of imprisonment must not exceed one-third of the non-parole period unless the court decides that there are special circumstances for it being more.1 Put another way, a non-parole period of a sentence of imprisonment must not be less than 75% of the full term of sentence (sometimes referred to as the head sentence) unless the court finds that there are special circumstances for it being less. Previous Judicial Commission studies2 reported that findings of special circumstances were very common. Indeed, the findings from one of these studies prompted the following comment by the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal in 2004:

THERE IS EVIDENCE THAT FINDINGS OF SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCES HAVE BECOME SO COMMON THAT IT APPEARS LIKELY THAT THERE CAN BE NOTHING SPECIAL ABOUT MANY CASES IN WHICH THE FINDING IS MADE.3

This study provides an empirical and legal analysis of cases dealt with on indictment in which findings of special circumstances have been made. It first reports the prevalence of findings of special circumstances between 1 January 2005 and 30 June 2012. It also identifies the degree to which sentences departed from the 75% statutory ratio. Finally, the study examines the factors which were found to warrant findings of special circumstances and their effect on the ratio between the non-parole period and the term of sentence.

The statutory rule

Section 44(1) of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 provides that when sentencing an offender to imprisonment for an offence, a court is first required to pronounce a non-parole period for the sentence. Section 44(2) further provides that the balance of the term of the sentence must not exceed one-third of the non-parole period for the sentence unless the court decides that there are special circumstances for it being more (hereafter described as the statutory rule). Section 44(2B) similarly provides that where a court sets an aggregate sentence of imprisonment, the balance of term must not exceed one-third of the non-parole period, unless the court finds that there are special circumstances. Both s 44(2) and s 44(2B) require the court to record its reasons for finding special circumstances.

The statutory rule in its current form was first introduced in NSW in 1989 with the enactment of the Sentencing Act 1989.4 A similar provision had been enacted in 1988 by an amendment to the Probation and Parole Act 1983. Section 20A of that Act provided the non-parole period for serious offences (as defined) shall be at least three quarters of the length of the sentence. Under s 21(3) a court could specify a shorter period only if it determines that the circumstances justify that course. Before the amendments, a non-parole period of three-quarters of the full term of sentence was regarded as being long and near the top of the range.5 It was accepted by the Court of Criminal Appeal6 and by the High Court in Griffiths v The Queen7 that since Parliament was aware of past sentencing practice, the amendment was plainly intended to have a punitive effect.8 The punitive effect of the amendment was however undermined by the discrepancy between the duration of non-parole periods imposed by courts and the time prisoners actually served taking account of remissions.9 Gleeson CJ explained the fictional element of the previous system in R v Maclay10 with reference to R v OBrien:11

THE SENTENCING JUDGE WAS SPECIFYING A PERIOD WHICH WAS DESCRIBED BY THE STATUTE AS A PERIOD BEFORE THE EXPIRATION OF WHICH THE PRISONER WAS NOT TO BE RELEASED ON PAROLE BUT THE LEGISLATION, AND THE REMISSIONS SYSTEM, PRODUCED THE QUALIFICATION THAT THE SO-CALLED NON-PAROLE PERIOD WAS, IN THE GREAT MAJORITY OF CASES, SUBSTANTIALLY LONGER THAN THE PERIOD THAT WAS ACTUALLY SERVED BEFORE RELEASE ON PAROLE.12

The Sentencing Act 1989 abolished the remissions system then operating in NSW. The new sentencing regime was considered harsh compared to its predecessor and it partly explained the increase in the prison population after 1989.13

It should be made clear from the outset that while fixing a non-parole period is important, it is but one part of the larger task of passing an appropriate sentence upon the particular offender.14 To focus only on that part of the sentence without regard to the full term of sentence is myopic because, as the High Court has held, it is always necessary to recognise that an offender may be required to serve the whole of the head sentence that is imposed.15 Indeed, the Court of Criminal Appeal has observed a period of parole is in itself a sentence16 even where a court orders release at the expiration of the non-parole period for sentences of 3 years or less under s 50 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act17

The harshness of any criminal justice system is ultimately measured by the rates of imprisonment, the lengths of the sentences imposed and the actual duration of incarceration. As the duration of incarceration will be significantly affected by the operation of the parole system,18 in making any assessment of punitiveness, it is necessary to take account of the rules which apply to both:

- the judicial task of fixing a sentence, including fixing the full term of sentence as well as fixing the non-parole period

- the release of offenders on parole either automatically19 or as a result of an eligibility assessment by the Parole Authority.20

Other jurisdictions

Notwithstanding the importance of focusing on the whole sentence (or full term of sentence), it is useful to compare the NSW position under s 44(2) to the approaches in other jurisdictions.

Victoria

The fixing of a non-parole period in Victoria is a matter for the courts discretion,21 subject to the statutory rule that it must be at least 6 months less than the head sentence.22 The Victorian Court of Appeal in R v Alparslan23 held that the sentencing judge erred in using as a benchmark his usual practice of fixing a non-parole period representing two-thirds of the head sentence: although there is a range into which many cases fall for the fixing of a non-parole period, it is not by reason of any standard practice.24

In an earlier case, R v Bolton,25 Callaway JA said:

THERE IS NO FIXED RATIO BETWEEN A HEAD SENTENCE AND A NON-PAROLE PERIOD. IN THE MAJORITY OF CASES THE PROPORTION IS BETWEEN TWO-THIRDS AND THREE-QUARTERS, BUT BOTH SHORTER AND LONGER PERIODS ARE FOUND.26

Later in R v Tran27 Redlich JA noted the following comment by the Australian Law Reform Commission and observed that it accords with the observations28 of Callaway JA above:

CASE LAW RECOGNISES THAT THE NON-PAROLE PERIOD IS GENERALLY SET AT 60 TO 66.6 PER CENT OF THE HEAD SENTENCE, WITH THE NON-PAROLE PERIOD INCREASING TO 75 PER CENT FOR THE WORST CATEGORY OF CASE.29

Murder and more serious crimes that attract longer sentences have a proportion which is higher than two-thirds and proportions exceeding 75% are not out of the ordinary.30

A proportion that exceeds 75% in the absence of an explanation may invite appellate scrutiny but does not inevitably lead to the conclusion that the sentencing judge has erred.31 There are several cases where the court has held that a high proportion set by the sentencing judge was appropriate in the circumstances of the case.32

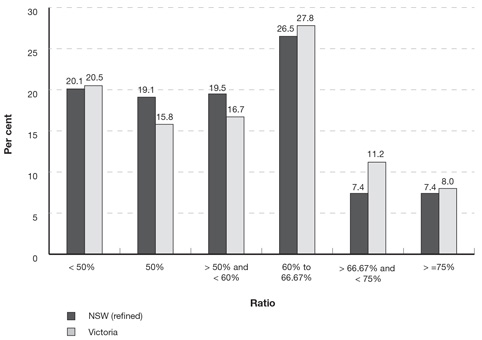

Following a request to the Sentencing Advisory Council of Victoria, the following statistics have been provided for the County and Supreme Courts of Victoria for the period 200708 to 201112:

- the most common ratio between the non-parole period and the full term of the overall sentence (effective sentence) was 50% (15.8% of cases)

- the non-parole was set at less than 50% (20.5% of cases); between 50% and 60% (16.7% of cases); at 60% to 66.67% (27.8% of cases); between 66.67% and 75% (11.2% of cases); and at 75% or higher (8.0% of cases)

- the average or mean ratio was 57.16%.33

Queensland

Like Victoria, the fixing of a non-parole period in Queensland is a matter for the courts discretion.34 There is no general rule as to what the numerical proportion should be between the non-parole period and head sentence.35 A court has a discretion to fix the eligibility date for parole subject to certain statutory exceptions.36 If no date has been set the prisoner is eligible for parole when half the sentence is served.37 The exceptions to this include: if the offender is subject to a serious violent offender declaration, or sentenced to more than 10 years imprisonment for a serious violence offence, the court cannot make a parole eligibility order until a minimum of 15 years or 80% of the sentence (whichever is lesser) has been served.38 Special parole eligibility provisions apply to prisoners serving sentences of life imprisonment.39

South Australia

For offences which do not fall within the statutory definition of a serious offence against the person,40 there is no prescribed numerical proportion between the non-parole period and the head sentence in South Australia. Since November 2007, a mandatory minimum non-parole period of four-fifths of the head sentence applies to offenders sentenced to imprisonment for a serious offence against the person.41 In fixing a non-parole period for an offence with a prescribed mandatory minimum non-parole period, the court may also:

- fix a non-parole period that is longer than the prescribed period if it is satisfied that the objective or subjective factors affecting the relative seriousness of the offence warrant such an order, or

- fix a shorter non-parole period if it is satisfied that special reasons exist to warrant such an order.42

Western Australia

There are two general statutory rules for fixing non-parole periods which apply in Western Australia:

- If the sentence of imprisonment is 4 years or less the prisoner is eligible for parole after half the sentence is served.43

- If the sentence is more than 4 years the prisoner is to be released 2 years before its expiration.44

Commonwealth

Part IB of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) makes exhaustive provision for fixing non-parole periods and making recognizance release orders for Commonwealth offences.45 Subject to some specific offence exceptions (for example, people smuggling and terrorism offences), there is no determined norm or percentage (of a head sentence) for a non-parole period or recognizance release orders for Commonwealth offences.46 It is wrong to begin from an assumed percentage such as 60 to 66% and then to identify special circumstances justifying a departure from it.47

The above comparison shows that NSW is one of the few Australian jurisdictions which has a peculiar statutory rule constraining a courts discretion when it sets a non-parole period. The statutory ratio is also relatively high.

The non-parole period and the purpose of parole

Any discussion of the relationship between the non-parole period and the balance of term or parole period inevitably raises the broader question of the purposes each serves.

It is well settled that the non-parole period is imposed because justice requires that the offender serve that period in custody.48 It is the minimum period of incarceration that the offender must spend in full-time custody having regard to all of the elements of punishment, including rehabilitation, the objective seriousness of the crime and the offenders subjective circumstances.49 Although the risk of re-offending is a relevant factor in setting the non-parole period, the sentence must always be proportionate to the crime. Preventative detention is not permitted.50

The parole period of a sentence serves other functions. After the offender has served the minimum period that justice requires, parole provides for mitigation of the punishment of the prisoner in favour of his rehabilitation through conditional freedom.51 The parole system was historically designed to encourage the offenders good behaviour during the non-parole period.52 However, during the parole period the focus is firmly on the rehabilitation of the offender. This includes ensuring that an offender will not re-offend by addressing underlying issues that bear upon the risk of recidivism.53 Rehabilitation includes the notion that the offender renounce their wrongdoing and establish or re-establish themselves as an honourable law abiding citizen.54 Rehabilitation is to be achieved while an offender is incarcerated, but also by way of treatment and supervision upon release. Parole supervision itself is an acknowledgement that offenders need a period to reintegrate and are often unable to prevent further offending when reliant upon their own motivation and resources.55

The concept of special circumstances in s 44(2) encompasses these principles concerning rehabilitation and the parole system. Allsop P recognised in Kalache v R56 that the concept of special circumstances bears upon an important element and purpose of the sentencing process, rehabilitation.57 However, the incongruity of tying s 44(2) to rehabilitation was observed by Spigelman CJ in R v Simpson:58

THE REQUIREMENTS OF REHABILITATION WOULD BE BEST COMPUTED IN TERMS OF A PERIOD OF LINEAR TIME, NOT IN TERMS OF A FIXED PERCENTAGE OF A HEAD SENTENCE. THE DESIRABILITY OF A LONGER THAN COMPUTED PERIOD OF SUPERVISION WILL BE AN APPROPRIATE APPROACH IN MANY CASES.59

How is s 44(2) applied?

The concept of special circumstances is firmly entrenched in sentencing law. An offenders legal representative is expected to make submissions addressing factors which may warrant a finding of special circumstances60 and particularly what is an appropriate period of supervision on parole for the offender.

The courts have developed principles which govern how the statutory rule should be applied in a given case, which have been refined over a nearly 25-year period. The following propositions can be drawn from the case law:

- The fact that s 44(1) provides that the court is first required to set a non-parole period does not mean that the non-parole period must first be determined61 or that a non-parole period should be set first, which is thereafter immutable.62 It is only the pronunciation of orders that is required to be done in that way.63

- The language of s 44(2) constrains the sentencing discretion by providing that the balance of term must not exceed the non-parole period by one-third unless the court finds special circumstances. There is, however, no corresponding rule that the balance of term must not be less than one-third of the non-parole period.64 It is advisable for the court to explain why a ratio in excess of 75% was selected to avoid an inference that an oversight must have occurred.65

- If there are circumstances that are capable of constituting special circumstances, the court is not obliged to vary the statutory ratio. Before a variation is made it is necessary that the circumstances be sufficiently special.66 The decision is first one of fact to identify the circumstances, and secondly one of judgment to decide whether the circumstances justify a lowering of the non-parole period below the statutory ratio.67 A finding of special circumstances is a discretionary finding of fact.68

- The full range of subjective considerations is capable of warranting a finding of special circumstances.69 It will be comparatively rare for an issue to be incapable, as a matter of law, of ever constituting a special circumstance.70 Findings of special circumstances have become so common that it appears likely that there can be nothing special about many cases in which the finding is made.71

- Generally speaking, the reform of the offender will often be the purpose in finding special circumstances, but this is not the sole purpose.72 An offenders good prospects of rehabilitation may warrant a finding of special circumstances.73 However, if an offender has poor prospects of rehabilitation and shows a lack of remorse, protection of the society may assume prominence in the sentencing exercise and militate against a finding of special circumstances.74 The risk of institutionalisation, even in the face of entrenched and serious recidivism may justify a finding of special circumstances.75> However, the existence of the factor does not require a finding.76 If institutionalisation has already occurred the focus may be on ensuring that there is a sufficient period of conditional and supervised liberty to ensure protection of the community and to minimise the chance of recidivism.77 An offenders youth,78 advanced age,79 the need to treat a drug addiction,80 ill health,81 mental illness,82 considerations of parity,83 and the fact that the offender will suffer harsher custodial conditions84have all been acknowledged as circumstances which may justify a finding of special circumstances.

- A finding of special circumstances permits an adjustment downwards of the non-parole period, but it does not authorise an increase in the term of the sentence.85 Nor should the formulation in s 44(2) be interpreted as a 75% statutory norm or as Gleeson CJ described it (the statutory predecessor to s 44(2)), a suggestion that the statutory ratio of 3:1 was a norm in the sense that variation in either direction, up or down, was, absent special circumstances, contrary to the statute.86 The extent of the adjustment is not determined by any norm and the court is to be guided by general sentencing principles.87

- Where special circumstances are found on the basis of the desirability of an offender undergoing suitable rehabilitative treatment, it is an error for a court to refrain from adjusting the sentence based on a view that the offender would benefit from treatment while in full-time custody.88 This is because full-time custody is punitive and treatment in prison is a matter in the executives discretion. An offender may not qualify for a program in custody or it may not be available.89

- The degree or extent of any adjustment to the statutory requirement is essentially a matter within the sentencing judges discretion90 including consideration of those circumstances which concern the nature and purpose of parole discussed above.91

- A court can have regard to the practical limit of 3 years on parole supervision which an offender may receive under cl 228 of the Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Regulation 2008.92 However, in the case of a serious offender,93 the period of supervision may be extended by, or a further period of supervision imposed of, up to 3 years at a time.94

- A purported failure to adjust a sentence for special circumstances raises so many matters of a discretionary character that the Court of Criminal Appeal has been very slow to intervene. As a practical matter, the court will only intervene if the non-parole period is manifestly inadequate or manifestly excessive.95 Ultimately the non-parole period that is set is what the court concludes, in all of the circumstances, ought to be the minimum period of incarceration.96

Where does s 44(2) fit in the sentencing exercise?

The High Court has made it clear that:

EXPRESS LEGISLATIVE PROVISIONS APART JUDGES AT FIRST INSTANCE ARE TO BE ALLOWED AS MUCH FLEXIBILITY IN SENTENCING AS IS CONSONANT WITH CONSISTENCY OF APPROACH AND AS ACCORDS WITH THE STATUTORY REGIME THAT APPLIES.97

There is no principle which:

DICTATES THE PARTICULAR PATH THAT A SENTENCER, PASSING SENTENCE IN A CASE WHERE THE PENALTY IS NOT FIXED BY STATUTE, MUST FOLLOW IN REASONING TO THE CONCLUSION THAT THE SENTENCE TO BE IMPOSED SHOULD BE FIXED AS IT IS. THE JUDGMENT IS A DISCRETIONARY JUDGMENT .98

In the case of s 44(2), Parliament has not prescribed at which stage of the sentencing exercise the court must consider the issue of special circumstances. The ratio in s 44(2) is not to be treated as a statutory norm. This was made clear in R v GDR99 and Caristo v R.100 One author has asserted that a significant number of NSW judges have applied s 44(2) as a prima facie position,101 that is, they have assumed that the balance of the term of the sentence must not exceed one-third of the non-parole period of the sentence and then enquired whether special circumstances exist which justify a longer parole period.102 He argues that the better approach is for the court to first apply general sentencing principles and determine a non-parole period and balance of term without reference to s 44(2).103 If the balance of term happens to exceed the non-parole period by one-third, the court then asks whether special circumstances exist.104 If the answer is no, a non-parole period of 75% of the term of the sentence will have to be imposed.105 If it is yes the initial determination, based on general sentencing principles, will stand. It is not clear how this second approach avoids double counting factors that have been taken into account in determining the head sentence.106 It is also not clear how the second approach applies in the case of sentencing for multiple counts where, although the same factors are relied on to justify a finding of special circumstances, the exercise of the discretion [to find special circumstances] may be productive of different results at different phases of the sentencing process.107 Arguably both approaches are erroneous because each introduces a bright line rule and each fails to have regard to the fact that the application of s 44(2) is inextricably linked to findings about an offenders rehabilitation. There is nothing in s 44 or the case law which mandates a method or, to adopt the High Courts term in Markarian v The Queen108 the path the sentencer must take.109 Section 44(2) is a conditional rule in respect of the balance of term of the sentence which is pronounced.

Data source and methodology

The following analysis examines sentencing cases finalised in the NSW District and Supreme Courts (the higher courts) for the period 1 January 2005 to 30 June 2012 (the reference period).110

First instance sentencing data are provided by the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) and then audited and processed to generate the statistics which appear on the Judicial Information Research System (JIRS). Using data from the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal database maintained by the Judicial Commission, the statistics on JIRS are adjusted or altered to take into account the outcomes of successful conviction or sentence appeals to the Court of Criminal Appeal and the High Court of Australia.111

JIRS statistics are appearance (or person) based, so that where an offender has been sentenced in more than one finalised court appearance during the reference period, the sentence imposed in each finalised court appearance is included.112 The sentence for the principal offence is shown in each case. Where an offender has been sentenced for multiple offences in a single finalised court appearance, the principal offence is the one that attracted the most severe penalty.113 The overall (or aggregate) sentence imposed is recorded in addition to the sentence imposed for the principal offence.114 Cases where either the full term or the non-parole period for the overall sentence exceeds the full term or non-parole period for the principal offence are referred to as consecutive cases. Non-consecutive cases are those where sentences are imposed for:

- one offence only

- multiple offences served wholly concurrently

- secondary offences which are subsumed within the sentence for the principal offence.

In such cases, the overall sentence will be the same as the sentence for the principal offence.

Exclusions

As the analysis of special circumstances is concerned with sentences of full-time imprisonment only, sentences for home detention and the now repealed sentencing option, periodic detention,115 are excluded from the study.116

Sentences of imprisonment imposed for Commonwealth offences are excluded from the study on the basis that Pt IB, Div 4 of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) makes exhaustive provision for the fixing of non-parole periods for these offenders.117

Fixed terms of imprisonment imposed for State offences where the sentencing judge declined to set a non-parole period (for the overall sentence) are also excluded as s 44(2) is not engaged.118

Mathematical approach to selection of special circumstances cases

The sentencing judges remarks on sentence were not available for the majority of cases in the study. Accordingly, whether the sentencing judge expressly made a finding of special circumstances and the reasons for making such a finding could not be ascertained directly. As a result, it was necessary to adopt a mathematical approach whereby it was surmised that a finding of special circumstances had been made in all cases where the non-parole period was less than three-quarters (or 75%) of the full term of sentence (the statutory ratio). Using this mathematical approach, the study identifies cases where findings of special circumstances were made in respect of the sentence imposed:

- for the principal offence

- at the overall (aggregate) sentence level.

Special circumstances calculated at the overall level

It was necessary to make a decision about whether the frequency of findings of special circumstances and the degree of departure from the statutory ratio in s 44(2) should be measured at the individual level, that is, by reference to the principal offence, or alternatively, at the overall level, that is, by reference to the overall sentence. For non-consecutive cases, it does not matter because the ratio at the principal offence level and the overall level is the same. However, where an offender is sentenced to consecutive sentences the ratios will be different in most cases. After careful consideration, the study adopts the overall level for the purpose of analysis. The reasons for adopting the overall level are considered briefly below and are further set out in Appendix A. In short, a measure based on the overall sentence more closely reflects sentencing practice and ultimately what occurred in the sentencing exercise.

Consequently, cases where a finding of special circumstances was made for the principal offence but not reflected in the overall sentence are excluded from the analysis.119 Conversely, the study includes cases where special circumstances were found for the overall sentence only.120

Reasons for using the overall sentence

Sentencing a person convicted of multiple offences is a notoriously complex task. Construed literally, s 44(2) applies to individual sentences; [and] does not apply, in terms, to an aggregation of several sentences.121 However, in practice the courts have not regarded themselves as limited by the literal reading of the provision and where a court made a finding of special circumstances for an individual offence it was assumed that that ratio is to be reflected in the overall sentence ratio, unless the judge expressly signifies otherwise.122 Where the judge expressed an intention that the finding not be translated to the overall sentence, there was no basis for appellate intervention on account of judicial omission.123 Further, there was no entitlement that the ratio calculated at the individual level be the same, or similar, at the overall level.124 Many of the appeal cases are collected in Kalache v R.125

Further, the courts apply the totality principle in consecutive cases by reducing the non-parole period for the principal offence where some form of accumulation is considered necessary.126 Hence, to use the sentence for the principal offence to determine whether special circumstances were found and to ascertain the degree of departure from the statutory ratio would distort the analysis.

It should also be noted that the concept of aggregate special circumstances has now been introduced in s 44(2A), a provision which a court may apply where it imposes an aggregate term of imprisonment under s 53A of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act.127

The influence of rounding sentences

It should be noted that in some cases the calculation of ratios between the non-parole period and the full term of sentence may be affected by rounding. In most cases where sentencing data were rounded up from days into whole months, the calculated ratio will be slightly higher than the true ratio had the number of days not been rounded up. This may have led to the rejection of some cases where special circumstances would otherwise have been found to exist using the mathematical approach above.128 On the other hand, a sentencing judge who has determined that an appropriate sentence involves days may have rounded down the sentence into complete months.129 This may have led to the acceptance of some cases where special circumstances would otherwise not have been found to exist. This may also have occurred in some cases where pre-sentence custody has been taken into account in sentences that were not backdated.130

Borderline cases

It should be noted that in some cases the ratio between the non-parole period and the full term of sentence was close to, but did not exceed 75%. In some of these cases, the sentencing judge may not have made a finding of special circumstances, thereby, slightly overstating the frequency of special circumstances cases.131

Reasons given for special circumstances

While the stated reasons for a finding of special circumstances could not be ascertained for the majority of cases in the study, an examination of a random sample of the available remarks on sentence and/or Court of Criminal Appeal judgments provide an insight into the common reasons for departing from the statutory ratio.132 While the reasons given in these cases are examined below, the analysis in the study largely focuses on a statistical analysis of available data to ascertain the relationship between certain factors and findings of special circumstances.

Measures used in analysis

The study employs two measures in its analysis:

- the frequency of findings of special circumstances

- the degree of departure from the statutory ratio for all cases and for special circumstances cases.

The latter measure uses the average value of all the ratios (mean ratio).133 The principal measure in the statistical analysis is the mean ratio for all cases, where lower mean ratios indicate a greater degree of departure from the statutory ratio. As each measure uses a base of 100, only one scale is provided in graphs.

While the analysis of the data is primarily descriptive, non-parametric tests of significance are used to ascertain whether there were any statistically significant bivariate relationships between certain factors and the various measures:

- The chi-square test is used for nominal data such as gender, plea and the frequency of findings of special circumstances.

- The Kruskal-Wallis test is used for interval and ordinal data such as age, length of overall full term of sentence and the mean ratio.

- Due to the effect that large sample sizes have on the chi-square statistic, measures of association are also used to determine the relative strength (or magnitude) of each relationship.

- Cramers V is used when assessing the strength of the relationship with the frequency of findings of special circumstances.

- Eta is used when assessing the strength of the relationship with the mean ratio.134

Results of analysis

Frequency of findings of special circumstances

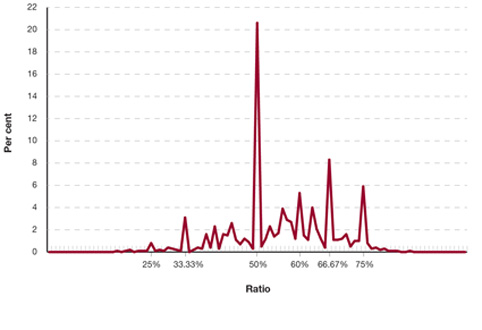

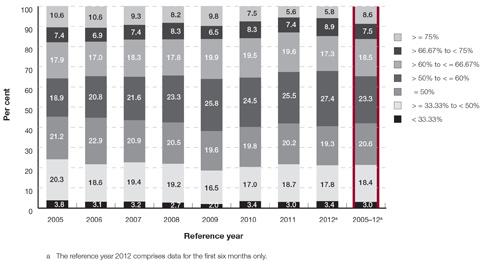

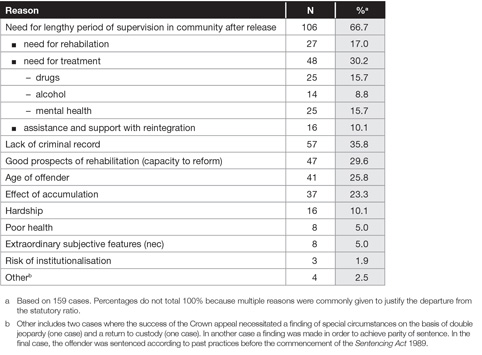

Figures 1 to 3 show the relationship between the non-parole period and the full term of the overall sentence for the 13,401 cases that fell within the parameters of the study:

- Figure 1 shows the ratios for cases in the reference period along a continuous scale.

- Figure 2 shows the ratios (grouped) for cases in the study by year.

- Figure 3 shows the frequency of findings of special circumstances and the mean ratio for all cases by year.

As all three figures show, special circumstances were found in the vast majority of cases (12,253 or 91.4%). As Figures 2 and 3 show, this high figure fluctuated slightly from year to year, ranging from 89.4% in 2005 and 2006 to 94.4% in 2011.135

Figure 1: Relationship between the non-parole period and the full term of the overall sentence (ratio)

Figure 2: Relationship between the non-parole period and the full term of the overall sentence by reference year and ratio grouping

Figure 3: Frequency of findings of special circumstances and the mean ratio between the non-parole period and full term of the overall sentence by reference year

Degree of departure from the statutory ratio

Figure 1 also shows that the most common ratio (by far) between the non-parole period and the full term of the overall sentence was 50%, that is, the non-parole period was set at half of the full term of the overall sentence (20.6% of cases). Other common ratios were 66.67%, or two-thirds, (8.3% of cases), 75% (5.9% of cases) and 60% (5.3% of cases).

As Figure 2 shows, 21.5% of cases had a ratio less than 50%; 42.0% had a ratio of 50% or less; 65.3% had a ratio of 60% or less; and 83.9% had a ratio of 66.67% or less. The mean ratio for all cases was 55.65% and the median ratio was 55.56%. The mean and median ratios for special circumstances cases were 53.73% and 53.33% respectively.

Figures 2 and 3 show there was little variation in the ratios from year to year.136

Reasons for finding special circumstances random sample

At least since R v Simpson137 it has been accepted that a wide range of factors is capable in combination (and sometimes in isolation) of constituting special circumstances. The real issue faced by the court in a given case is whether it should find special circumstances and vary the statutory ratio.138 According to the Court of Criminal Appeal, a finding of special circumstances must be purposeful and s 44(2) cannot be utilised just to relieve the offender from serving the non-parole period.139

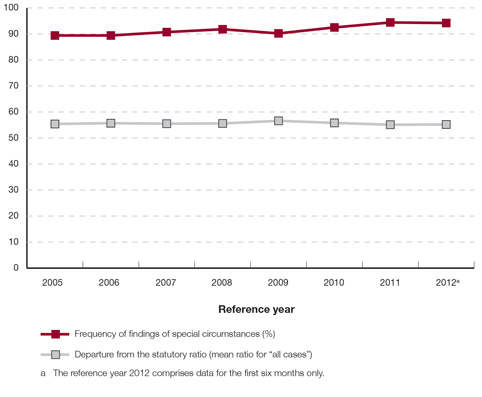

As mentioned earlier, a random sample of 159 judgments in which a finding of special circumstances was expressly made were examined to ascertain the reasons for departing from the statutory ratio (random sample cases).140 Table 1 lists the reasons given for finding special circumstances in the random sample cases.

Table 1: Reasons given in random sample cases for varying the statutory ratio

It is worth first noting that usually more than one reason was given (78% of random sample cases): 37.7% (two reasons), 22.6% (three reasons), 11.9% (four reasons) and 5.7% (five or more reasons). Only 22% cited a single reason.

The most common reason given was the offenders need for a lengthy period of supervision in the community after release (66.7%), followed by the lack of prior criminal record (35.8%) these mostly referred to the offender serving their first prison sentence. Other common reasons were good prospects of rehabilitation (29.6%), age of the offender (25.8%) (particularly their youth), the effect of accumulation (23.3%), and hardship of custody (10.1%). The reasons given should not be viewed in isolation. There is a clear interrelationship between the different reasons included in Table 1. For example, a need for a lengthy period of supervision encompasses the need for:

- an offenders rehabilitation

- assistance and support with reintegration into the community

- treatment for alcohol or drug dependency

- treatment to address mental health issues.

The offenders age and first time in custody were the reasons given in 25 cases. These offenders were mostly young people, but there was a small group of older offenders: three were in their sixties, one in his fifties and one in his late forties.

It should be noted that in Collier v R141 McClellan CJ at CL had considerable reservations142 as to whether the fact that a person would be in custody for the first time or has no previous convictions were of themselves reasons capable of justifying a finding of special circumstances.143 This is because they are matters that will already have been taken into account when the court set the full term of sentence and the non-parole period, and should not be a source of further leniency.144 In the present study, this reason was the only one given to justify a finding of special circumstances in just 5 random sample cases (3.1%). In the other cases, it was combined with age, the need for supervision and the need for reintegration into the community.

The type, frequency and pattern of reasons given in Table 1 are broadly consistent with the findings of an analysis undertaken in an earlier Judicial Commission robbery study.145

Factors associated with special circumstances

As stated above, there is a wide range of factors which are capable of constituting special circumstances. As remarks on sentence were not available in the majority of cases, the available data were examined to assess other possible factors and their relationship to findings of special circumstances.

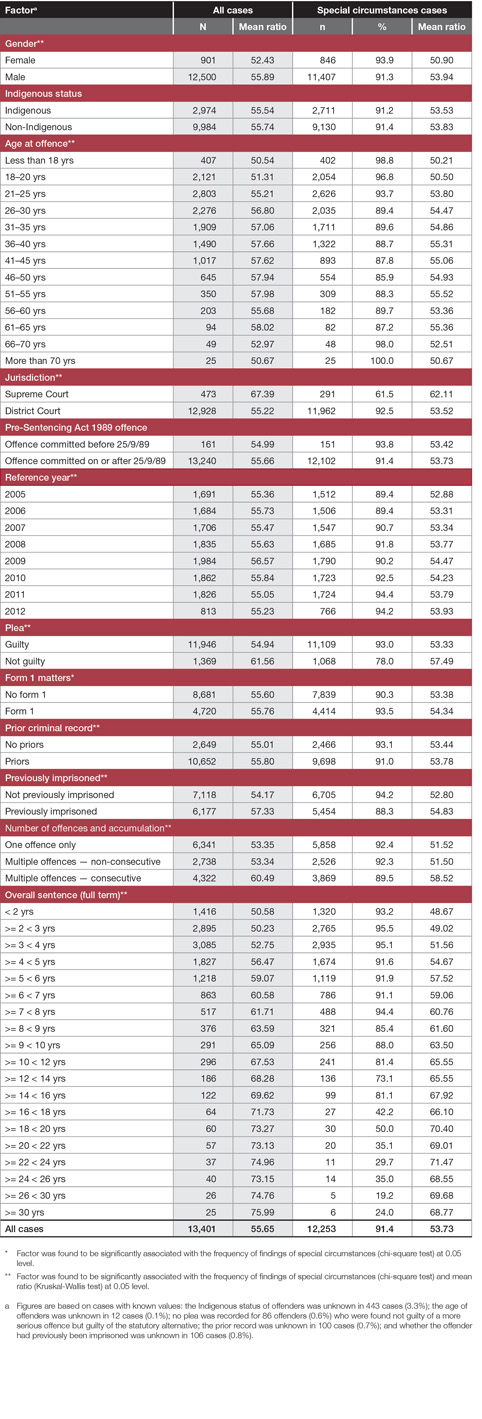

Table 2 shows the bivariate relationship between each factor and:

- the frequency of findings of special circumstances

- the degree of departure from the statutory ratio for all cases and for special circumstances cases.

While the bivariate relationship between the factors and findings of special circumstances is shown in Table 2, it should be acknowledged that it would be unusual for a single factor to warrant a finding of special circumstances. It should also be acknowledged that there are other factors for which no data were available such as an offenders need for rehabilitation or need for treatment for alcohol or drug dependency.

Two factors with ordinal data length of overall full term and age of offender are also displayed graphically in Figure 4 and Figure 5 respectively.

Relationship with the frequency of findings of special circumstances

With the exception of the factors Indigenous status and whether or not the offence was committed before the Sentencing Act 1989, there was a statistically significant relationship between the factors in Table 2 and the frequency of findings of special circumstances. However, the strength of the association was weak for most factors.

The factor with the strongest association was the length of the overall full term of sentence.146 The jurisdiction of the court147 and plea148 had the next strongest association. It should be pointed out, however, that both of these factors had a significant and strong interrelationship with the length of the overall full term that may account for the differences.149

Relationship with the degree of departure from the statutory ratio

When the analysis focused on the degree of departure from the statutory ratio, the same factors referred to above, with the exception of Form 1 matters, were found to have a statistically significant relationship with the mean ratio for all cases. Once again, the strength of the association was weak for most factors.

In order of the magnitude of the association, the following offenders departed from the statutory ratio to a greater extent (lower mean ratio) than their respective counterparts set out in Table 2:

- offenders sentenced to an overall full term shorter than 4 years150

- offenders sentenced for one offence only or offenders given non-consecutive sentences for multiple offences151

- juveniles or young offenders aged 1820 years or offenders aged over 65 years152

- offenders sentenced in the District Court153

- offenders who pleaded guilty154

- offenders not previously imprisoned155

- offenders sentenced in reference year 2011 or 2012156

- offenders with no prior convictions157

- female offenders.158

Table 2: Relationship between certain factors and the frequency of findings of special circumstances and the mean ratio between the non-parole period and full term of the overall sentence

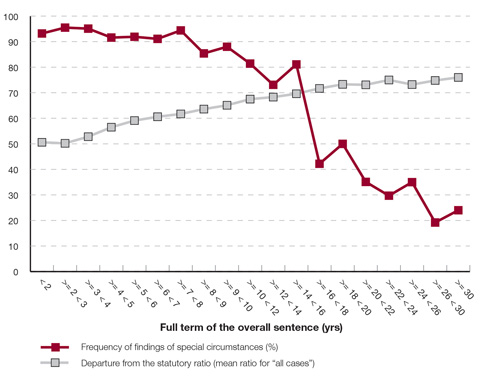

Length of overall full term

In any functional system of criminal justice it is imperative that those who are imprisoned address underlying issues that bear upon the risk of recidivism both while in prison and on release. As stated earlier, the system of parole is designed to achieve that end. As a practical matter, an offender must have a sufficient period of supervision. Parole supervision for up to 3 years can be imposed, after which time the offender is expected to have reintegrated into the community. Section 44(2) sets a 25% parole period unless there are special circumstances. Consequently, the scope for supervision will depend on the length of the overall full term of sentence. There is less scope for supervision for shorter sentences compared with longer sentences. For example, a sentence of 2 years imprisonment without a finding of special circumstances will result in a maximum parole period of 6 months. On the other hand, a sentence of 12 years without a finding of special circumstances will result in a maximum of 3 years parole. Therefore one would expect that shorter sentences of imprisonment are more likely to attract findings of special circumstances than longer sentences, and further, shorter sentences will have a greater degree of departure from the statutory ratio (that is, lower mean ratios) than longer sentences.

The full term of overall sentences in the study ranged from 7 months to 43 years with a median term of 3 years and 6 months. In the absence of a finding of special circumstances, the maximum parole period for the median term would be 10.5 months. The distribution of the overall full terms in the study is shown below as well as the maximum parole period without a finding of special circumstances:

- 17.1% of overall full terms were 2 years or less (6 months)

- 61.6% of overall full terms were 4 years or less (12 months)

- 90.1% of overall full terms were 8 years or less (24 months)

- 94.1% of overall full terms were 10 years or less (30 months)

- 96.1% of overall full terms were 12 years or less (36 months).

Given the supervision period for shorter sentences, it is unsurprising that a finding of special circumstances was made in the vast majority of those cases. Conversely, the longer the sentence, the lower the frequency of findings of special circumstances, demonstrating that the utility of finding special circumstances diminished the longer the sentence because the period of supervision would have been considered sufficient.

As shown, the length of the overall full term had the strongest association with the frequency of findings of special circumstances and the degree of departure from the statutory ratio. Figure 4 shows there was a noticeable decline in the frequency of findings of special circumstances when the overall full term reached 8 years and a further dramatic decline when the overall full term reached 16 years. The vast majority of sentences of less than 8 years attracted a finding of special circumstances (93.8%) compared with sentences of 8 years but less than 16 years (82.8%) and sentences of 16 years or more (36.6%).

Figure 4 also shows that as the length of the overall full term increased so did the ratio between the non-parole period and the full term of sentence. As mentioned above, the lowest mean ratios were observed for offenders sentenced to an overall full term shorter than 4 years (50.58% for sentences less than 2 years, 50.23% for sentences of 2 years but less than 3 years and 52.75% for sentences of 3 years but less than 4 years).

Figure 4: Frequency of findings of special circumstances and the main ratio between the non-parole period and full term of the overall sentence by length of overall sentence

Other factors

Three of the factors in Table 2 were also identified in Table 1 as reasons for finding special circumstances in the random sample cases: age of offender, whether the offender had been previously imprisoned and whether the offender was sentenced to consecutive sentences.

Age

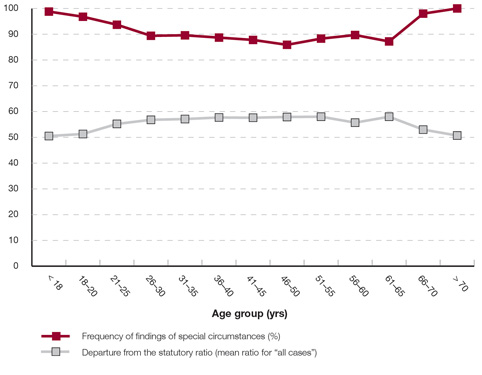

As Figure 5 shows, special circumstances were found more frequently for the youngest offenders (98.8% for juveniles and 96.8% for offenders aged 1820 years) and for the oldest offenders (100% for offenders aged over 70 years and 98.0% for offenders aged 6670 years). These offenders also had the greatest departure from the statutory ratio, recording the lowest mean ratios (50.54%, 51.31%, 50.67% and 52.97% respectively). These offenders accounted for around one in five cases in the study. Juvenile offenders represented 3.0% of cases, offenders aged 1820 years represented 15.8% of cases and offenders aged over 65 years represented 0.6% of cases.

Figure 5: Frequency of findings of special circumstances and the mean ratio between the non-parole period and full term of the overall sentence by age of offender

Previously imprisoned

Just over half (53.5%) of the offenders in the study had not been imprisoned previously. Special circumstances were found more frequently for these offenders (94.2%) than for offenders who had been imprisoned previously (88.3%). They also recorded a lower mean ratio (54.17% compared with 57.33%).

Consecutive sentences

Almost one-third (32.3%) of cases in the study were consecutive cases. However, these cases were less likely to attract special circumstances (89.5%) compared with non-consecutive cases (92.3%). This finding was also reflected in the higher mean ratio (smaller degree of departure from the statutory ratio) observed for consecutive cases (60.49%) compared with non-consecutive cases (53.34%).

This finding is perhaps not surprising since the imposition of consecutive sentences was a factor found to be significantly associated with the length of the overall full term of sentence.159

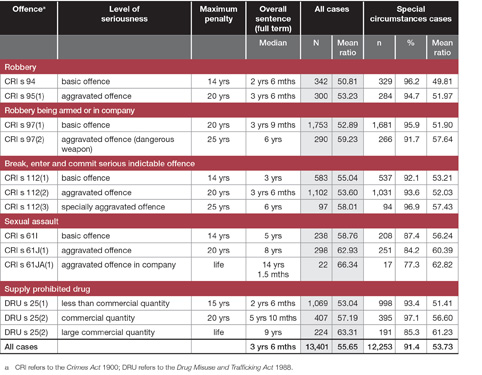

Particular offences

The analysis so far has focused on the overall picture without taking account of individual offences. This section examines particular offences in relation to the frequency of findings of special circumstances and the degree of departure from the statutory ratio where special circumstances were found. In particular where there was a:

- low frequency of findings and a small departure (high mean ratio)

- low frequency of findings but a large departure (low mean ratio)

- high frequency of findings and a large departure (low mean ratio)

- high frequency of findings but a small departure (high mean ratio).

From the hundreds of offence categories dealt with in the higher courts, over half had fewer than 10 cases finalised in the reference period. The analysis below is limited to offences with more than 10 cases. Due to the high frequency of findings of special circumstances overall, the analysis focuses on offences where there was:

- a low frequency of findings of special circumstances

- the greatest departure from the statutory ratio.

Low frequency of findings of special circumstances

Murder

The offence of murder recorded the lowest frequency of findings of special circumstances (30.1%) and also had the smallest departure from the statutory ratio where special circumstances were found (mean ratio = 70.37%). When all murder sentences were included, the mean ratio was 74.23%. This is unsurprising given the long duration of murder sentences (median full term was 21 years 10 months) and limited utility of an extended period of supervision. It also explains why jurisdiction as a factor (all murder cases are prosecuted in the Supreme Court) had a strong association with findings of special circumstances.

An examination of murder cases where special circumstances were found revealed that these cases were more likely than cases without a finding of special circumstances to comprise:

- younger offenders (49.2% were 25 years or under compared with 29.0%), and in particular juvenile offenders (15.9% compared with 2.8%)

- offenders not previously imprisoned (74.6% compared with 58.2%)

- offenders who pleaded guilty (54.0% compared with 41.1%).

They were also more likely to incur overall full terms less than 16 years (17.5% compared with 3.4%).

An earlier Judicial Commission study of sentencing levels for murder from 19901993 found sentences typically departed from the one-third formula160 and that the typical sentence comprised a minimum term of 12 years and an additional term of 6 years,161 that is, a ratio of 66.67%. Another Judicial Commission study of sentences in 1992 found special circumstances in just over 60% of murder cases.162 Further, it found that murder was one of the most common offences where a finding was made.163

The present study shows that special circumstances were found less frequently and there was less departure from the statutory ratio for this offence. This is consistent with a Judicial Commission study of sentences in 2002 which found that the ratio between the non-parole period and the full term of the sentence was 75% or more in 77.1% of cases, including 6 life sentences.164 When the six life sentences are excluded, special circumstances were found in only 27.6% of cases.165

Other offences

A number of other offences also had a relatively low frequency of findings of special circumstances and relatively small departures from the statutory ratio where special circumstances were found. These offences were (in order of degree of departure for all cases):

- certain other attempts to murder (Crimes Act 1900, s 29): 57.1% and 67.21% respectively (mean ratio for all cases = 70.96%)

- acts done to the person with intent to murder (Crimes Act 1900, s 27) 64.0% and 64.73% respectively (mean ratio for all cases = 68.70%)

- attempts to choke, etc (garrotting) (Crimes Act 1900, s 37): 54.5% and 62.20% respectively (mean ratio for all cases = 68.27%).

Escape lawful custody

The distinctive feature of sentencing for the escape offence is that the court is obliged to impose a sentence which is consecutive on any existing non-parole period(s).166 This constraint on the sentencing discretion may require the court to adjust the non-parole period for the escape offence downwards in order to properly apply the principle of totality.167 While the offence of inmate escape or attempt to escape lawful custody (Crimes Act 1900, s 310D(a)) recorded a relatively low frequency of findings of special circumstances (69.2%), it had one of the greatest departures from the statutory ratio where special circumstances were found (mean ratio = 46.01%). When all escape sentences were included the mean ratio was 55.53%.

Greatest departure from the statutory ratio

A more useful measure than the frequency of findings of special circumstances is the degree of departure from the statutory ratio for all cases. For example, there were 15 offences where special circumstances were found in every case. However, the degree of departure from the statutory ratio for those offences varied from 47.44% to 59.17%. Furthermore, there were a number of offences where the frequency of findings of special circumstances was not quite as high as 100%, although the degree of departure was much greater than for some of those offences that attracted special circumstances in every case.

The following five offences had the greatest departure from the statutory ratio. The frequency of findings of special circumstances and the degree of departure from the statutory ratio where special circumstances were found are set out below (in order of degree of departure for all cases):

- indecent assault on female (Crimes Act 1900, s 76 (rep)): 100% and 47.44% respectively (mean ratio for all cases = 47.44%)

- demanding property with intent to steal (Crimes Act 1900, s 99(1)): 96.4% and 47.44% respectively (mean ratio for all cases = 48.43%)

- indecent assault on male (Crimes Act 1900, s 81(rep)): 100% and 48.58% respectively (mean ratio for all cases = 48.58%)

- aggravated breaking out of dwelling-house after committing, or entering with intent to commit, indictable offence (Crimes Act1900, s 109(2)): 100% and 49.34% respectively (mean ratio for all cases = 49.34%)

- stealing property in a dwelling-house (Crimes Act 1900, s 148): 81.8% and 44.69% respectively (mean ratio for all cases = 50.20%).

It was not possible to ascertain directly why these five offences departed the most from the statutory ratio. However, the departure may be explained, in part, by factors such as an offenders need for a longer period of supervision than the statutory ratio would allow and/or the age of the offender. With the exception of the offence of aggravated breaking out of dwelling-house after committing, or entering with intent to commit, indictable offence (which also has the highest maximum penalty), the offences received, on average, sentences less than the overall median full term of 3 years and 6 months the lowest was 22.5 months for stealing property in a dwelling-house. Two offences (aggravated breaking out of dwelling-house after committing, or entering with intent to commit, indictable offence and demanding property with intent to steal) were disproportionately committed by young offenders aged 25 years or under (71.4% and 44.4% respectively). As for the two repealed indecent assault offences (one repealed in 1981 and the other in 1984), not only were these offenders much older when they came to be sentenced (median age was 69 years and 68 years respectively), but only one offender had previously been imprisoned. Further, the fact that they were required to be sentenced according to past practices (see below) may also have justified a finding of special circumstances.168

Pre-Sentencing Act 1989 offences

Where an offender committed an offence before the Sentencing Act 1989 commenced, the court is required to set the non-parole period according to past practices. It has been held that the statutory sentencing regime applicable to the old offending may itself justify a finding of special circumstances, quite apart from other subjective features which may have done so.169

In the present study, there were 161 such cases and special circumstances were found in 151 of these (93.8%) and the degree of departure from the statutory ratio for all cases was 54.99%. In these cases, the fact that an offender was sentenced according to past practices may have been one of several reasons why special circumstances were found which justified a variation from the statutory ratio.

Offence seriousness and special circumstances

The final analysis tests the proposition that shorter sentences of imprisonment are more likely to attract findings of special circumstances than longer sentences, and further, that shorter sentences will have a greater degree of departure from the statutory ratio (that is, lower mean ratios) than longer sentences.

The 10 most common offences in the study were identified. Eight were a basic or an aggravated (or a more serious) form of the same offence. These have been selected for analysis and are grouped as follows:

- robbery

- robbery being armed or in company

- break, enter and commit a serious indictable offence

- supply prohibited drug.

A further offence group, sexual assault, was selected on the basis that an aggravated form of the offence was in the top 10.

While there may have been forms of offences within these offence groups which did not fall within the top 10 offences, they were included in the analysis in order to demonstrate the effect of offence seriousness on the frequency of findings of special circumstances and the degree of departure from the statutory ratio.

Each offence group represents a discrete statutory scheme with graduating levels of seriousness both because of the maximum penalty and the circumstances of aggravation or seriousness. Two of the five offence groups had two levels of offence seriousness and three offence groups had three levels. Together, these 13 offences accounted for just over half of the cases in the study (50.2%).

Table 3 sets out the particular offences within each group. For each offence it shows the statutory maximum penalty, the median full term of the overall sentence, the frequency of findings of special circumstances and the degree of departure from the statutory ratio (for all cases and for special circumstances cases). It is clear from Table 3 that within each offence group, the more serious the offence the longer the sentence. If the proposition stated above holds, one would expect:

- fewer findings of special circumstances as the seriousness of the offence increases, and

- a smaller degree of departure from the statutory ratio the more serious the offence.

Table 3: Offences within selected offence groups and their relationship to findings of special circumstances and the mean ratio between the non-parole period and full term of the overall sentence.

Table 3 largely confirms the above proposition. It shows that for every offence group, except break, enter and commit a serious indictable offence, the mean ratio for all cases increased as the seriousness of the offence increased. With the exception of break, enter and commit a serious indictable offence and supply prohibited drug, the frequency of findings of special circumstances also decreased as the seriousness of the offence increased. In the case of supply prohibited drug, while the frequency of findings was higher for offences involving a commercial quantity of drugs than for offences involving less than a commercial quantity, the degree of departure from the statutory ratio was considerably less.

The break and enter exception

Table 3 shows different results for the offence group of break, enter and commit a serious indictable offence. The specially aggravated form of the offence under s 112(3) had the highest frequency of special circumstances (96.9%) but the smallest departure from the statutory ratio (58.00%). The aggravated form of the offence under s 112(2) had a slightly higher frequency of findings of special circumstances (93.6%) and a slightly greater departure from the statutory ratio (53.60%) than offences committed under s 112(1) (92.1% and 55.04% respectively). Further analysis of the data revealed that there were factors which might explain these differences.

At least three factors were at play:

- the jurisdictions in which the offences can be dealt with

- age of the offenders

- previous offending.

It is axiomatic that these factors interrelate.

Section 112(3) is a strictly indictable offence and also a serious childrens indictable offence.170 These offences are dealt with on indictment in the higher courts. Unlike s 112(3), an offence under s 112(2) is strictly indictable for adult offenders, but children may be dealt with in the Childrens Court.171 Section 112(1) offences can be dealt with summarily in the Local Court172 or the Childrens Court.

Consequently, there was a higher number of young offenders in the study aged under 21 years (41.2%, including 20.6% who were juvenile offenders) who committed s 112(3) offences. However, the degree of departure from the statutory ratio for s 112(3) offences was not as great as the other offences within the offence group. This may reflect the necessity for the non-parole period to represent the seriousness of the offence. In the case of offences under s 112(1) and s 112(2), the counterintuitive results may be explained by differences in offender characteristics. First, as s 112(1) can be dealt with summarily, it would be expected that the cases dealt with in the higher courts fell into the more serious category. Further, the vast majority of offenders who committed an offence under s 112(1) had previously been imprisoned (86.7%, including 79.0% for an offence of the same type). Further, only 7.9% were aged less than 21 years. In comparison, offenders who committed an offence under s 112(2) were less likely to have been previously imprisoned (69.4%, including 58.1% for an offence of the same type), and were more likely to be aged less than 21 years (28.5%). These factors age and reduced prospects of rehabilitation have a direct bearing on the issue of special circumstances as the discussion above illustrates.

Conclusion

The concept of special circumstances in s 44(2) remains an integral part of the sentencing process for State offences. The provision should neither be applied as a statutory norm nor necessarily be taken into account as the last consideration in the sentencing exercise. It is an essential tool used to address the offenders rehabilitation. Since the statutory ratio is set at 75%, NSW has one of the harshest sentencing statutes in Australia.

During the reference period, special circumstances were found in 91.4% of 13,401 cases where a non-parole period was set for the overall sentence. However, this figure of itself does not address or inform the degree to which sentences imposed by courts depart from the statutory ratio in s 44(2). When the degree of departure from the statutory ratio was analysed, the most common ratio between the non-parole period and the full term of the overall sentence was 50%. This was found in 20.6% of cases. The non-parole period was set at less than 50% in 21.5% of cases and set at between 50% and 75% in 49.4% of cases. In almost a quarter of cases (23.9%), the non-parole period was set at 60% to 66.67%. The average, or mean, ratio was 55.65%. These findings were broadly comparable with sentences imposed in Victoria.

A finding of special circumstances cannot be made simply to relieve an offender of a longer non-parole period. It must ordinarily serve a purpose related to the offenders need for an extended period of supervision. A discrete analysis of a random sample of 159 judgments where a finding of special circumstances was made revealed that usually more than one reason was provided by the court and the factors cited were often interrelated. These included the offenders:

- need for a lengthy period of supervision to enable professional support and assistance

- lack of criminal history (serving a first prison sentence)

- good prospects of rehabilitation

- age (particularly their youth).

The effect of accumulation of sentences was also cited as a factor. Sentencing judges appear to be largely following the Court of Criminal Appeal position that an offenders first time in custody is not, of itself, a sufficient reason to make a finding of special circumstances. In only 5 cases (3.1%) was this the only reason cited.

The data was examined to gauge the effect of other possible factors and their relationship to findings of special circumstances. The length of the overall full term had by far the strongest association with the frequency of findings of special circumstances and the degree of departure from the statutory ratio. As the length of the overall full term increased so did the ratio between the non-parole period and the full term of sentence. The lowest mean ratios were observed for offenders sentenced to an overall full term shorter than 4 years (50.58% for sentences less than 2 years, 50.23% for sentences of 2 years but less than 3 years and 52.75% for sentences of 3 years but less than 4 years).

It is clear that the need for the court to utilise s 44(2) reduces the longer the duration of a sentence. For example, the most serious offence in the criminal calendar, murder, had the lowest frequency of findings of special circumstances (30.1%) and the highest mean ratio (74.23%) of any offence in the study. This also held true where we controlled for the offence using specific offence groupings with graduating levels of seriousness: the more serious the offence, the longer the sentences. There were fewer findings of special circumstances and smaller degrees of departure from the statutory ratio the more serious the offence (subject to some explicable exceptions). This was evidence of a diminution in the weight attributed to factors capable of finding special circumstances. It also indicated that the period of supervision was adequate without a finding being made under s 44(2).

The study therefore confirms that a wide range of factors, often considered in combination, are capable of justifying a finding of special circumstances. The weight attributed to these factors diminishes the more serious the offence and the longer the sentence. In every case there is the prevailing consideration that the court must impose a non-parole period which represents the minimum period that justice requires the offender spend in full-time custody.

Appendix A: The calculation of special circumstances

The following sets out the rationale for the method used to measure both the frequency of findings of special circumstances and the degree of departure from the statutory ratio in s 44(2). The measurement was straightforward where the offender was sentenced for only one offence (6,341 or 47.3% of cases analysed). The difficulty arises where an offender is sentenced for more than one offence.

The issue is whether special circumstances should be calculated at the individual level, that is, by using the ratio for the principal offence only, or alternatively, whether it should be calculated at the overall level, that is, the ratio between the non-parole period and full term of the overall sentence. Where the offender is sentenced to wholly concurrent sentences, or where secondary offences are subsumed within the sentence for the principal offence (2,738 or 20.4% of cases analysed), it does not matter because the ratio at the principal offence level and the overall level is the same. However, the ratio will be different in most cases where consecutive sentences are imposed, or where an aggregate sentence is imposed under the recently enacted s 53A of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act (4,322 or 32.3% of cases analysed).

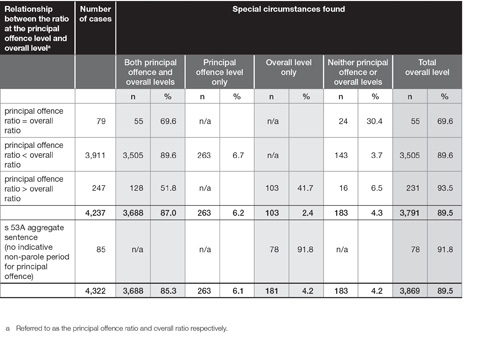

Table A shows the relationship between the ratio at the principal offence level (principal offence ratio) and the ratio at the overall level (overall ratio) and findings of special circumstances for the 4,322 cases where multiple sentences were imposed and where some form of accumulation occurred. It divides the cases into four possible sentencing scenarios:

- where the principal offence ratio is equal to the overall ratio

- where the principal offence ratio is less than the overall ratio

- where the principal offence ratio is more than the overall ratio

- where a s 53A aggregate sentence was imposed and a non-parole period was not indicated for the principal offence.

It also shows how often special circumstances were found at the principal offence level and at the overall level.

Table A shows overwhelmingly that the principal offence ratio was less than the overall ratio (3,911 of 4,322 cases). In only 79 cases was the principal offence ratio the same as the overall ratio and in only 247 cases was the principal offence ratio more than the overall ratio. Table A also shows that in 263 cases special circumstances were found for the principal offence but not at the overall level. Conversely, in 103 cases the ratio was less than 75% of the overall sentence but 75% or higher for the principal offence.

Table A: Relationship between the ratio at the principal offence level and the overall level and findings of special circumstances for consecutive cases

These figures clearly reveal that the degree of departure from the statutory ratio was greater at the principal offence level than at the overall level. It confirms the accepted sentencing practice of reducing the non-parole period for the principal offence where some form of accumulation is necessary in order to apply the principle of totality (discussed in the study).

If the study were to only use the ratio for the principal offence rather than the ratio for the overall sentence there is a real danger of presenting a distorted picture of special circumstances particularly with regard to the degree of departure from the statutory ratio. The reality is that where an individual sentence is part of a larger exercise, the ratio of the non-parole period to the full term of sentence for the individual sentence cannot convey an accurate picture of what occurred in the sentencing exercise. The ratio set by the court for the overall sentence provides a much more accurate picture as it takes account of the structure of the whole sentence and the principle of totality. It may explain why a court has refrained from finding special circumstances on the basis that there was a sufficient period of supervision inherent in the sentence.

Another good reason for using the ratio for the overall sentence is that it was not possible in some cases to derive a ratio for the principal offence where an aggregate sentence under s 53A was imposed. Under s 53A a court is not required to indicate a non-parole period for offences that do not carry standard non-parole periods. Table A shows that a non-parole period was not indicated for the principal offence in 85 of 113 cases where an aggregate sentence was imposed. Put alternatively, a non-parole period was only indicated in 28 of 113 cases.

Since the analysis adopts the overall level, the 263 cases where a finding of special circumstances was made for the principal offence but not reflected in the overall sentence are excluded from the analysis. Conversely, the study includes the 181 cases where special circumstances were found for the overall sentence only, including 78 aggregate sentencing cases where there was no indicative non-parole for the principal offence.

Appendix B: Ratio between the nono-parole period and term of sentence: NSW and Victoria comparison

Although there is no rule in Victoria which corresponds to the statutory rule in NSW, it is worthwhile making a jurisdictional comparison of the ratios between the non-parole periods and terms of sentence for cases dealt with on indictment (presentment).

The Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council provided sentencing data for a 5-year period 200708 to 201112. The data, like this study, exclude fixed term sentences and the ratios have been calculated at the overall (or effective) level. However, unlike this study, the data include sentences for Commonwealth offences. Note also that the statistics on JIRS are adjusted or altered to take into account the outcomes of successful conviction or sentence appeals.

In order to make a more meaningful comparison with Victoria, the NSW data have been refined to include Commonwealth offences and to cover the same reference period from 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2012. During this period, NSW dealt with 9,943 cases compared with 4,635 cases in Victoria. Figure B shows the ratios (grouped) for both jurisdictions.

While a similar pattern was observed for the ratio groupings in each jurisdiction, Figure B shows that:

- higher courts in NSW set a non-parole period at 50% and less than 60% more often than Victoria (38.5% compared with 32.5%)

- higher courts in Victoria set a non-parole period between 66.67% and 75% more often than NSW (11.2% compared with 7.4%).

Overall, the non-parole period was set at less than 75% in both jurisdictions in the vast majority of cases (92.6% in NSW and 92.0% in Victoria). The average, or mean, ratio was 55.87% and 57.16% respectively.

Figure B: Relationship between the non-parole period and the full term of the overall sentence by jurisdiction and ratio grouping (1 July 2007 to 30 June 2012)

Endnotes

1 Sentencing Act 1989, s 5(2) (rep) (effective 25 September 1989 to 2 April 2000), re-enacted with terminology changes by the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999, s 44(2) (effective 3 April 2000).

2 See I MacKinnell, D Spears and R Takachi, Special circumstances under the Sentencing Act 1989 (NSW), Research Monograph No 7, Judicial Commission of NSW, 1993; J Keane, P Poletti and H Donnelly, Common offences and the use of imprisonment in the District and Supreme Courts in 2002, Sentencing Trends & Issues, No 30, Judicial Commission of NSW, Sydney, 2004; P Poletti, Z Baghizadeh and P Mizzi, Common offences in the NSW higher courts: 2010, Sentencing Trends & Issues, No 41, Judicial Commission of NSW, Sydney, 2012.

3 R v Fidow [2004] NSWCCA 172 per Spigelman CJ at [20], commenting on the findings of the study reported in Keane, Poletti and Donnelly, ibid.

4 s 5.

5 Griffiths v The Queen (1989) 167 CLR 372.

6 R v Griffiths (unrep, 23/3/89, NSWCCA) at 1112.

7 (1989) 167 CLR 372.

8 ibid per Gaudron and McHugh JJ at 391.

9 Second Reading Speech, Sentencing Bill, Legislative Assembly, Debates, 10 May 1989, p 7905; R v Maclay (1990) 19 NSWLR 112 at 121. See also D Weatherburn and R Howie, Disappearing non-parole periods and the sentencers dilemma (1985) 9(2) Crim LJ 72.

10 (1990) 19 NSWLR 112 at 121.

11 [1984] 2 NSWLR 449.

12 (1990) 19 NSWLR 112 at 121.

13 E Matka, NSW Sentencing Act 1989, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Sydney, 1991; A Johnston and D Spears, The Sentencing Act 1989 and its effect on the size of the prison population, Research Monograph No 13, Judicial Commission of NSW, Sydney, 1996, and references cited therein at pp 2628.

14 Muldrock v The Queen (2011) 244 CLR 120 at [17].

15 PNJ v The Queen (2009) 83 ALJR 384 at [11].

16 R v Moore [2012] NSWCCA 3 at [38].

17 ibid.

18 For example, where parole has been refused by the Parole Authority, an offender may not apply again for parole for a further nine months and that application must not be considered by the Parole Authority more than 60 days before the offenders annual review date: Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Act 1999, s 137A. Note that s 137A is subject to s 137B and the Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Regulation 2008, cl 233. Parole systems differ across the States and Territories. For a comparison of these see Sentencing Advisory Council (Vic), Review of the Victorian Adult Parole System, Report, March 2012, App 3, pp 108119, at <www.sentencingcouncil.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/Review of the Victorian Adult Parole System Report.pdf>, accessed 11 June 2013.

19 Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act, ss 50, 51; Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Act 1999, s 159 (sentence of imprisonment for a term of 3 years or less).

20 Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Act 1999, Pt 6.

21 R v Harkness [2001] VSCA 87 at [24]; Sentencing Act 1991 (Vic), s 11(1).

22 Sentencing Act 1991 (Vic), s 11(3).

23 (2007) 170 A Crim R 205.

24 ibid at [24]. See also Vujasic v R [2011] VSCA 229 at [10].

25 R v Bolton & Barker [1998] 1 VR 692.

26 ibid at 699.

27 [2006] VSCA 222.

28 ibid at [27].

29 Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC), Same crime, same time: sentencing of federal offenders, ALRC Report 103, Canberra, 2006, Ch 9 at [9.26].

30 R v Romero (2011) 32 VR 486 at [26].

31 Green v R [2011] VSCA 236 at [17].

32 Mann v R [2011] VSCA 189; Mokbel v R [2011] VSCA 106; Vujasic v R [2011] VSCA 229; Green v R [2011] VSCA 236.

33 Unpublished data provided by S Farrow, Chief Executive Officer, Sentencing Advisory Council (Vic), 17 June 2013. The ratios provided are for all cases where a non-parole period was set. These findings are compared with NSW in Appendix B.

34 Subject to comity considerations between courts exercising federal jurisdiction: R v Mokoena [2009] 2 Qd R 351 at [12].

35 Penalties and Sentences Act 1992 (Qld), ss 160B160D.

36 ibid s 160A(5).

37 Corrective Services Act 2006 (Qld), s 184(2).

38 ibid s 182; Penalties and Sentences Act 1992 (Qld), s 161A, Sch 1.

39 Corrective Services Act 2006 (Qld), ss 181, 181A.

40 Criminal Law (Sentencing) Act 1988 (SA), s 32(10)(d).

41 ibid s 32(5). Note that a mandatory minimum parole period of 20 years also applied if a court was sentencing a person to life imprisonment for murder.

43 ibid s 32A.

43 Sentencing Act 1995 (WA), s 93(1).

44 ibid. See also s 94 of the Sentencing Act 1995 (WA) as to how that jurisdiction calculates eligibility dates for parole where the prisoner is serving more than one sentence.

45 Hili v The Queen (2010) 242 CLR 520 at [22].

46 ibid at [13], [37][38].

47 ibid at [44].

48 Muldrock v The Queen (2011) 244 CLR 120 at [57].

49 Power v The Queen (1974) 131 CLR 623 at 628629, applied in Deakin v The Queen (1984) 58 ALJR 367; R v Simpson, Caristo v R [2011] NSWCCA 7 at [27].

50 Veen v The Queen (No 2) (1988) 164 CLR 465 at 477.

51 Crump v NSW (2012) 86 ALJR 623 per French CJ at [28], quoting Deakin v The Queen (1984) 58 ALJR 367 at 367.

52 R v Maclay (1990) 19 NSWLR 112 at 116117.

53 R v Pogson (2012) 82 NSWLR 60 at [101].

54 ibid at [122].

55 M Pearse, The effectiveness of probation and parole supervision in NSW (2012) 24(7) JOB 53 at 55.

56 [2011] NSWCCA 210.

57 ibid at [2]; see also per Buddin J at [45].

58 (2001) 53 NSWLR 704.

59 ibid at [58].

60 Edwards v R [2009] NSWCCA 199 at [11]; Jinnette v R [2012] NSWCCA 217 at [96].

61 Musgrove v R (2007) 167 A Crim R 424 at [44].

62 R v Way (2004) 60 NSWLR 168 at [111][113], citing R v Moffitt (1990) 20 NSWLR 114.

63 Eid v R [2008] NSWCCA 255 at [31].

64 Musgrove v R (2007) 167 A Crim R 424 at [27]; DPP (NSW) v RHB (2008) 189 A Crim R 178 at [17], [19]; Wakefield v R [2010] NSWCCA 12 at [26].

65 Wakefield v R, ibid at [26]; Briggs v R [2010] NSWCCA 250 at [34].

66 R v Fidow [2004] NSWCCA 172 per Spigelman CJ at [22].

67 R v Simpson (2001) 53 NSWLR 704 at [73]; Fitzpatrick v R [2010] NSWCCA 26 at [36].

68 R v El-Hayek (2004) 144 A Crim R 90 at [103]; Caristo v R [2011] NSWCCA 7 at [28].

69 R v Simpson (2001) 53 NSWLR 704 at [46], [60].

70 ibid.

71 R v Fidow [2004] NSWCCA 172 at [20].

72 R v El-Hayek (2004) 144 A Crim R 90 at [105].

73 Arnold v R [2011] NSWCCA 150 at [37]; RLS v R [2012] NSWCCA 236 at [120].

74 R v Windle [2012] NSWCCA 222 at [55].

75 Jackson v R [2010] NSWCCA 162 at [24].

76 Dyer v R [2011] NSWCCA 185 at [50]; Jinnette v R [2012] NSWCCA 217 at [98].

77 Jinnette v R, ibid at [103].

78 AM v R [2012] NSWCCA 203 at [86]; Kennedy v R (2008) 181 A Crim R 185 at [53].

79 R v Mammone [2006] NSWCCA 138 at [54].

80 Sevastopoulos v R [2011] NSWCCA 201 at [84][85].

81 R v Mammone [2006] NSWCCA 138 at [54].

82 Muldrock v The Queen (2011) 244 CLR 120 at [58]; Devaney v R [2012] NSWCCA 285 at [92].

83 Tatana v R [2006] NSWCCA 398 at [33].

84 Mattar v R [2012] NSWCCA 98 at [23][25], but see RWB v R (2010) 202 A Crim R 209 at [192][195].