Introduction

This Sentencing Trends & Issues reports on penalties imposed in the NSW Local Court for environmental planning and protection offences in the 5-year period from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2013 (the study period). For the purposes of the study, environmental planning and protection offences (referred to below as environmental offences) are offences that fall within Class 5 of the Land and Environment Court (LEC) jurisdiction as defined in s 21 of the Land and Environment Court Act 1979 (LEC Act).1 While there are a number of penalty types which the Local Court may impose for these offences, a fine is the most common. The study presents findings about fines imposed by the Local Court on both individuals and corporations. It focuses on the seven most common environmental offences and identifies recent trends in fine amounts for these offences. The study is the first of two dealing with environmental crime. A forthcoming publication will examine sentencing in the LEC.

It is firmly established that in seeking sentencing consistency, the courts must have regard to what has been done in other cases. It is the role of the court to synthesise information about the sentences imposed in comparable cases and other raw material2 such as sentencing statistics.3 Sentencing for environmental offences can be difficult because of the broad range of circumstances under which the offences are committed. Offenders can range from individuals to small business operators, privately-owned companies, public companies and multinational corporations. Environmental offences typically encompass a wide range of conduct. The objective seriousness of offences can vary from offences which cause substantial harm to the environment to those where there is very little or no harm. The mental ingredient of offences can range from absolute liability or strict liability to negligent or intentional acts. Offences which are committed for commercial gain will carry a high degree of culpability. On the other hand, an offence may be committed simply as a result of Homer Simpson-like incompetence and without any foresight.

Since the Local Court deals with environmental crimes infrequently, at least compared to other more common crimes, magistrates may be less familiar with the subject matter of these offences and the sentencing principles that apply. The decisions in Bentley v BGP Properties Pty Ltd4 and Bankstown City Council v Hanna,5 several articles6 of the Chief Judge of the LEC, the Honourable Justice Brian J Preston, and the establishment of the LEC database on the Judicial Information Research System (JIRS)7 all provide significant guidance for the Local Court. The Chief Judge has commented that in appeals from the Local Court to the LEC, magistrates remarks on sentence often contain a discussion of the relevant sentencing principles that apply to environmental offences.8

Current issues

It is important to place sentencing for environmental offences in the Local Court within the broader context of the prosecution of environmental crime. It is a complex and wide-ranging area of law. Offences against the environment are prevalent. For example, putting to one side all the work of the NSW Environment Protection Authority (the EPA), one local council reported that it received approximately 1,000 complaints each month in respect of Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 (POEO Act) matters.9 Given that there are 152 local councils in NSW, each with its own environmental enforcement responsibilities, the scale of the problem is apparent.10

Illegal waste dumping is a particular problem. Then Minister for the Environment, the Honourable Robyn Parker MP, said that these incidents were causing significant and long-lasting environmental harm, associated clean-up costs and unpaid waste levies,11 and were estimated to cost the NSW government $100 million per year.12 The government has set aside $20 million for anti-littering programs over the next four years, which includes $2.4 million in litter grants for local councils.13

Criminal prosecution is only one part of the armoury used by the State government to protect the environment. Under Pt 8.4 of the POEO Act, civil proceedings may be brought to remedy or restrain breaches of the Act or to restrain breaches which cause, or are likely to cause, harm to the environment. In its prosecution guidelines,14 the EPA says that s 219(3) of the POEO Act allows it to pursue non-prosecution options to prevent, control, abate or mitigate any harm to the environment caused by an alleged offence.15 Regulatory authorities, including the EPA and local councils, are empowered to issue environment protection notices such as clean-up notices and prevention notices.16 Prohibition notices may also be issued by the Minister administering the POEO Act on the recommendation of the EPA.17 The EPA provides local councils with guidance on the use of notices in an instructional document on its website.18 The EPA may also accept written enforceable undertakings from alleged offenders instead of prosecuting.19

The following current issues which affect the prosecution of environmental offences are discussed below:

- the 2012 increase in the jurisdictional limit of the Local Court to impose monetary penalties under the POEO Act

- the complexity of prosecution arrangements for environmental offences

- the use of penalty notices

- recent and proposed offences.

The sentencing guideline for England and Wales will also be briefly mentioned.20

Increase in the Local Courts jurisdictional limit

The most notable recent development has been the five-fold increase in the jurisdictional limit of the Local Court for the monetary penalty it can impose for an offence under the POEO Act. In February 2012, the maximum monetary penalty that the Local Court can impose for an offence increased from $22,000 to $110,000.21 It remains the case that Tier 1 offences under the POEO Act the most serious environmental offences involving wilful or negligent conduct22 cannot be dealt with in the Local Court.23 Proceedings for other offences under the POEO Act and the regulations made under the Act are Tier 2 offences.24 These may be dealt with summarily by the Local Court or the LEC in its summary jurisdiction.25 Tier 3 offences are Tier 2 offences that can be dealt with by way of penalty notice under Pt 8.2.26

The jurisdictional monetary penalty increase, coupled with the recent Court of Criminal Appeal (CCA) decision in Harris v Harrison,27 will inevitably have the effect that cases of environmental crime that would otherwise have been dealt with in the LEC, will now be dealt with by the Local Court. The effect of is to discourage prosecutors from prosecuting offences in the LEC where the likely penalty in a case falls within the monetary penalty jurisdiction of the Local Court. Although the offence in Harris could have been disposed of either in the Local Court or the LEC,28 it was prosecuted in the LEC. The CCA held that the jurisdictional limit of the Local Court should have been brought to the judges attention, especially given that the judge had assessed the offence as one of low objective gravity.29 The fact that the offence ought to have been dealt with in the Local Court meant that the jurisdictional limit of the Local Court should have been regarded as a highly significant sentencing factor.30 The CCA held that the appellants liability for costs should be assessed as if the proceedings were brought in the Local Court.31 The CCAs approach to the assessment of costs in Harris will no doubt be a relevant consideration for prosecutors where they have a choice of (court) forum. In the LEC, it is usual practice for the prosecutor to obtain legal costs following a successful conviction and/or sentencing of an offender. Costs can be very substantial.32 The EPAs prosecution guidelines also state that the jurisdictional limit of the Local Court is a consideration where it has a choice of forum.33

The increase in the Local Courts jurisdiction under the POEO Act to $110,000 is arguably too high because it will remove the bulk of cases from the specialised jurisdiction of the LEC. The latter court deals with the more serious environmental crimes which often require the reception of complex expert evidence, lengthy conviction and sentence proceedings, a familiarity with LEC decisions, and an in-depth understanding of sentencing principles as they relate to environmental offences. The precise impact on the flow of cases following Harris is not altogether clear. However, it is worth noting that between January 2000 and September 2013 only five offenders dealt with in the LEC for offences under the POEO Act received a fine for a principal offence in excess of $110,000.34 Although the Local Court has a jurisdictional limit of $110,000 under s 127(3) of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (EPA Act), the offences under the EPA Act are planning-related and generally involve less complex factual and legal issues than many of those found in the POEO Act.

Under the POEO Act, where a court finds an offence against the Act or regulations proved, it may make orders in addition to any penalty that may be imposed35 or regardless of whether any penalty is imposed, or other action taken, in relation to the offence.36 The Local Court is constrained in the additional orders it can make under s 250 of the POEO Act, notwithstanding the increase in the monetary penalties it can impose.37 The court is not permitted to make certain orders, including orders that the offender:

- carry out a specified project for the restoration or enhancement of the environment in a public place or for the public benefit (s 250(1)(c))

- carry out a specified environmental audit of activities carried on by the offender (s 250(1)(d))

- pay a specified amount to the Environmental Trust established under the Environmental Trust Act 1998 (s 250(1)(e))

- provide a financial assurance (s 250(1)(h)).

Given the increase in the jurisdictional limit of the Local Court, perhaps it would be timely to consider an expansion of the additional orders which can be made by the Local Court.

There are a number of offences in the POEO Act that have a maximum penalty exceeding the jurisdictional monetary maximum of $110,000 in the Local Court, for example, pollute waters under s 120(1) and unlawfully transport waste under s 143(1). Magistrates must not regard the jurisdictional limit of the Local Court as some form of maximum penalty or a penalty reserved for the worst category of an offence.38 The maximum penalty for the offence rather than the jurisdictional limit is the appropriate sentencing reference point.39 The jurisdictional limit is only engaged where the court considers the sentencing result should be above the jurisdictional limit.40

Prosecution arrangements

The desirability of consistency of approach is not limited to sentencing. It extends to the prosecution process. No other area of the criminal law has such complex prosecution arrangements as environmental law. While the EPA is the lead prosecutor of environmental offences, it records in its prosecution guidelines that it is one of many prosecutors and

[o]

rganisations such as local councils, NSW Maritime, police and water supply authorities as well as individuals in the community may bring proceedings in their own right.41

The fact that there are so many entities which prosecute environmental offences some with their own guidelines and/or enforcement policies increases the risk of inconsistency in the enforcement of environmental law. It also affects which cases come before the Local Court. Inconsistency can occur because of the lack of uniformity of approach by prosecutors. As stated earlier, there are 152 local councils in NSW. Section 6(2) of the POEO Act provides that the local authority is the appropriate regulatory authority for non-scheduled activities,42 subject to some exceptions. Non-scheduled activities include pollution of storm water, illegal dumping, and pollution arising from a development site. The EPA prosecution guidelines for the offences under the POEO Act do not bind local councils, but according to the EPA provide a framework 43 can be achieved. The NSW Department of Planning & Environment has its own prosecution guidelines,44 and many local councils also have their own enforcement policies.45

Consistency of approach in the enforcement of environmental law has been identified as a problem by the Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal (IPART).46 IPART is reviewing local government and compliance enforcement, including the enforcement of environmental law. IPART commented that

[c]

onsistency of approach is more challenging with 152 different council regulators, than with a single State agency regulator.47 Seven councils reported to IPART that sometimes there is uncertainty as to who is the appropriate regulatory authority under the POEO Act.48 IPART recommended in a recent draft report that the EPA should, subject to a cost-benefit analysis, engage in a partnership model with local government to reduce inconsistency of approach.49 The EPA currently assists local councils by offering education courses about their regulatory responsibilities under the POEO Act, and by the provision of various toolkits and guides.50 IPART also recommended that the NSW Ombudsman should be given a statutory responsibility to develop and maintain a more detailed model enforcement policy and updated guidelines for use by councils to guide on-the-ground enforcement.51 The availability of local council resources has been raised as an issue. The Productivity Commission found State governments increasingly rely on local government to implement environmental law.52 However, local councils have limited skills and resources to do so.53

The EPA has come under parliamentary scrutiny and has been the subject of criticism from a number of quarters.54 There was an unsuccessful attempt to regulate its power to prosecute serious offences, partly because it had opted to take civil action (rather than criminal proceedings) against a serial offender who had dumped waste containing asbestos fragments.55 The NSW Auditor-General was recently critical of the EPAs regulation of contaminated sites on public and private land.56 The NSW Nature Conservation Council has also criticised the EPA for too frequently issuing penalty notices rather than prosecuting offenders in court where offenders are exposed to higher penalties.57 A Parliamentary Committee of Inquiry into the general performance of the EPA was established in June 2014. The Committee will report on the performance of the EPA by measuring its recent performance against its objectives pursuant to section 6 of the Protection of the Environment Administration Act 1991.58 The Committees final report is due in early 2015.

Penalty notices

It is common for environmental crimes to be dealt with by way of a penalty notice. A penalty notice is a notice to the effect that the person to whom it is directed has committed an offence and if the person does not wish to have the matter dealt with by a court, the person may pay the specified amount for the offence.59 The Protection of the Environment Operations (General) Regulation 2009 lists the offences and penalty notice amounts under the POEO Act.60

The cases dealt with by the Local Court in this study represent only a very small fraction of all environmental offences committed. The cases that reach the courts are the tip of the iceberg. For example, for the financial year 20122013, the EPA reported that EPA/Office of Environment and Heritage officers issued 1,440 penalty notices and NSW local government officers issued 5,486.61 Those entities issued penalty notices as follows:

- all pollute water offences under the POEO Act: 467 penalty notices

- POEO other offences (including the offences of transporting/depositing waste unlawfully and contravene licence conditions): 485 penalty notices

- littering offences: 4,366 penalty notices.62

For the previous financial year, the EPA reported that EPA/Office of Environment and Heritage officers issued 1,651 penalty notices and NSW local government officers issued 6,172.63 Those entities issued penalty notices as follows:

- all pollute water offences under the POEO Act: 599 penalty notices

- POEO waste: all other offences (that is, other than littering offences): 922 penalty notices

- littering offences: 4,993 penalty notices.64

To put these penalty notice figures into perspective, there were only 3,052 environmental offences65 dealt with in the Local Court in the 5-year study period: including only 136 pollute water cases; 171 unlawful transport/deposit waste or fail to comply with requirements relating to waste transportation cases; and 452 deposit or aggravated deposit litter cases. The sentencing data include cases where the offender contested a penalty notice and those where the prosecutor commenced proceedings by way of a court attendance notice.

The widespread use of penalty notices to enforce environmental law raises various issues explored in the NSW Law Reform Commission Report on the subject.66 These include:

- how should penalty notice offences be selected?

- should there be a set of guidelines for setting penalty notice amounts?

- who should issue such notices?

- how should they be enforced?67

The penalty notice amounts are very low for some offences. This is no doubt a reflection of the fact that environmental offences typically cover a very broad range of conduct. For example, in the study period, the offence of pollute waters under s 120(1) of the POEO Act attracted a maximum fine of $1 million in the case of a corporation if dealt with by a court, compared to $1,500 when dealt with by way of a penalty notice.68

While penalty notices are efficient and cost-effective, there is always the danger that they will be overused by prosecutors. As stated above, the EPA is the lead prosecutor in the area of environmental offences. It has specific prosecution guidelines for penalty notices.69 However, the EPA states in its guidelines:

The EPA has no direct control over how authorised officers from other organisations carry out their duties. In the interest of fairness and consistency, it is recommended that all authorised officers implement the guidelines set out here in relation to penalty notices.70

For example, the NSW Department of Planning & Environment has its own compliance and enforcement penalty notice guidelines which address when a penalty notice would be an appropriate response to offences committed under the EPA Act.71

The EPA prosecution guidelines state that a penalty notice may be suitable in instances where the breach is minor; the facts are apparently incontrovertible; the breach is a one-off and can be remedied easily; and where the notice is likely to be a practical and viable deterrent.72

The penalty notice amount for an offence should be proportionate, or bear some relation, to the seriousness of the offence. One objective of a system of penalty notices is to provide an option for an offender to pay an amount which is lower than the sentence that would otherwise be imposed if the matter went to court.73 The Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council expressed the view that a reasonable test as to whether an infringement penalty amount is proportionate is whether it is lower than the majority of sentences for cases prosecuted in court by a charge.74 It found that for common summary offences, the infringement penalty amount was higher than at least 75% of sentencing outcomes.75

The recent debate in NSW has centred on whether the penalty notice amounts for environmental crimes under the POEO Act are too low. The one-size-fits-all approach to penalty notices is fundamentally flawed because of the range of offenders who commit environmental crimes, as discussed above. The question that arises is whether the current level of penalty notice amounts for common environmental offences borrowing the words of the High Court concerning civil penalties in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd 76 are regarded by offender[s] or others as an acceptable cost of doing business.77 More recently, in Bankstown City Council v Hanna, Chief Judge Preston said that the penalties need to be of such magnitude to deter financially78 other would-be offenders. If an offender simply factors penalty notices and court fines into the cost of doing business, environmental law loses it deterrent value. In the area of illegal dumping, then Minister for the Environment, Ms Robyn Parker MP, said that offenders simply factor the cost of penalties into their business models.79

In order to be effective, a penalty notice should create a real economic disincentive for the offender to repeat the conduct. As it was put in the England and Wales sentencing guideline for environmental offences (concerning court fines):

The fine should meet, in a fair and proportionate way, the objectives of punishment, deterrence and the removal of gain derived through the commission of the offence; it should not be cheaper to offend than to take the appropriate precautions.80

It is now acknowledged that penalty notice amounts for environmental crimes under the POEO Act are not sufficiently proportionate and require substantial reform. The Honourable Rob Stokes MP, Minister for the Environment, expressed the view that NSW has penalties that are simply not significant enough to change poor behaviour.81 Under the Protection of the Environment Operations (General) Amendment (Fees and Penalty Notices) Regulation2014 (which commenced on 29 August 2014), penalty notice amounts for the most serious offences under the POEO Act (including, ss 91, 97, 120, 128, 142A, 143 (asbestos or hazardous waste, or any other waste exceeding prescribed volume or weight) and 144) have been substantially increased.82 The penalty amount depends on who issues the penalty notice.83 Where the penalty notice is served by the officer of a local authority (that is, a local council), the penalty amount is $8,000 for corporations (from $1,500) and $4,000 for individuals (from $750).84 Where the penalty notice is served by any other officer empowered to do so (such as an officer of the EPA), the penalty notice amount increases to $15,000 for corporations and $7,500 for individuals. For other POEO Act offences (ss 124, 125, 126, 143 (other waste), 152 and 167), where the penalty notice is served by the officer of a local authority, the penalty amount is $4,000 for corporations (from $1,500) and $2,000 for individuals (from $750).85 Where the penalty notice is served for these offences by any other officer empowered to do so (such as an officer of the EPA), the penalty notice amount increases to $8,000 for corporations and $4,000 for individuals. These reforms represent a significant break from the past. Many more offenders may elect to contest their penalty notice in the Local Court.

On 2 March 2009, penalty notice amounts for certain offences under the EPA Act also increased.86 The effect of penalty notice amount increases on sentencing in the Local Court is considered below.

The Protection of the Environment Legislation Amendment Act 2014, which was assented to on 28 October 2014 but is yet to commence, also takes a new approach to penalty notices under the Radiation Control Act 1990 and the Contaminated Land Management Act 1997 by considering what the offender has done in the past. It will amend those Acts to provide that different amounts of penalties can be prescribed based on the number of times that an offender has been convicted of, or paid a penalty notice for, the same offence within a 5-year period.

Enforcement of penalty notices

Under environmental legislation, designated authorised officers (the EPA, local councils, NSW Roads and Maritime Services and police) have a discretion to caution an offender, to serve a penalty notice for identified offences, or to commence proceedings in the Local Court. Where a penalty notice is issued but not paid, it must be enforced. The NSW Ombudsman office, has undertaken significant work87 on the issue of how local councils enforce penalty notices.88It found that the approach taken by at least four local councils to representations about fines lacked consistency and transparency.89 Outcomes depended on whether the representations were sent to the State Debt Recovery Office (SDRO) or the issuing council.90 The NSW Ombudsman office suggested inconsistencies of approach to enforcement between local councils could be remedied by having a single avenue of review.91 In straightforward matters, this could be the SDRO.92 For example, the SDRO have created review guidelines for littering offences.93 The NSW Ombudsman opined that where offences are more complex, and require indepth knowledge of legislation, representations about fines should be dealt with by the issuing authority.94 This would include some environmental crimes, such as pollute water and waste disposal offences. Suffice to state that the problems identified in relation to the enforcement of penalty notices for environmental offences are part of the broader issue of consistency of approach between local councils. Applying a uniform enforcement policy as recommended by IPART may reduce the problems.

Penalty notices and sentencing

The cases in this study fall into three broad categories:

- a penalty notice has been issued and the alleged offender chooses to contest the matter in the Local Court

- the prosecutor has initially issued a penalty notice but decided to withdraw it and proceed by way of a court attendance notice95

- the prosecutor has decided not to issue a penalty notice and to proceed by way of a court attendance notice.

An unrepresented person who contests a penalty notice should arguably be given a Parker v DPP-type warning96 by the magistrate on the ground of procedural fairness.97Parker holds that if, in a severity appeal from the Local Court to the District Court, the judge is contemplating an increased sentence, he or she must indicate this fact so that the appellant can consider whether or not to apply to withdraw the appeal.98 Contesting a penalty notice can be perilous. In Cameron v Eurobodalla Shire Council,99 the offender was issued a penalty notice of $600 for removing trees to obtain a better view. He contested the matter in the Local Court and was fined $10,000 and ordered to pay the prosecutors costs of $2,980. He unsuccessfully appealed against the severity of his sentence and was ordered to pay more costs.

When an alleged offender decides to contest a penalty notice in court, several issues arise. First, should the court, prima facie, regard the offence as being one that falls at the lower end of the range of seriousness given the EPA and NSW Department of Planning & Environment prosecution guidelines on penalty notices? This is certainly a matter which the court may wish the prosecutor to address. Ultimately, it is the task of the court to make findings about the seriousness of the offence.100 Secondly, should the court have any regard to the prescribed penalty notice amount in determining the sentence? On one view, the penalty notice amount, prima facie, sets a baseline level or a yardstick for a less serious form of an offence. The LEC has held repeatedly101 that the prescribed amount of a penalty notice is not a relevant consideration. This is because of the terms of s 37 of the Fines Act1996.102 The penalty notice amount is also irrelevant where the prosecutor proceeds by way of a court attendance notice rather than a penalty notice.103 The courts task is to impose a sentence which takes account of all the circumstances of the offence, the offenders means to pay, and the offenders prior record. It is doubtful whether the proposed increases in penalty notice amounts could be interpreted by the courts as an indication from Parliament that it intended that those offences should be treated more seriously. Traditionally, an increase in the maximum penalty for an offence (not the penalty notice amount) is an indication that Parliament requires the courts to treat the offence more seriously.104 Nevertheless, an increase in the amount of a penalty notice, as the discussion below will show, may have the effect of increasing sentencing levels for an offence. Finally, should a court have regard to the fact an offender has been issued with penalty notices in the past for similar offending? In Bankstown City Council v Hanna, Preston CJ took that consideration into account in the context of a discussion of the offenders prior record.105

Recent and proposed offences

The Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment Bill 2014, which was introduced into the NSW Parliament on 22 October 2014, will, if enacted, introduce a three-tier offence regime for breaches of planning laws based on the seriousness of the offence. For the most serious breaches (those committed intentionally and which caused, or were likely to cause, significant harm to the environment or the death of, or serious injury or illness to, a person), the Bill provides for a maximum penalty of $5 million for companies and $1 million for individuals. Under the amendments, there will be no change to the Local Court jurisdictional limit of $110,000 under s 127(3) of the EPA Act. It is also worth noting that the amending Bill imports the POEO Act, Pt 8.3, Court orders in connection with offences (which includes the additional orders discussed above) for offences under the EPA Act. However, Pt 8.3 will only apply to proceedings before the Court for offences under the EPA Act or regulations.106 Court is exhaustively defined in s 4 of the EPA Act as the LEC.

Brief mention should also be made of the new offences of being a repeat waste offender107 and knowingly supplying false or misleading information about waste which commenced on 1 October 2013.108 Proceedings for these new offences cannot be dealt with in the Local Court.109 This gives recognition to both the serious nature of the new offences and the specialised jurisdiction of the LEC.

Recent developments in England and Wales

As mentioned previously, England and Wales have a (12-step) sentencing guideline for environment offences, which has been in operation since 1 July 2014.110 Under ss 142 and 143 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 (UK), the court must have regard to the purposes of sentencing and the seriousness of the offence. The latter requires a consideration of the culpability of the offender and the harm or potential harm caused to the environment.111 If the court chooses to impose a fine, it must enquire into the offenders financial circumstances and impose a fine which reflects the seriousness of the offence.112 In the case of corporate offenders:

The fine must be fixed to meet the statutory purposes with the objective of ensuring that the message is brought home to the directors and members of the company (usually the shareholders).113

Data source and methodology

For the purposes of the study, environmental planning and protection offences (which as stated earlier are referred to as environmental offences) are offences that fall within Class 5 of the LEC jurisdiction as defined in s 21 of the LEC Act. Section 21 is reproduced in Appendix A. The abbreviations adopted below for specific Acts and regulations are set out in Appendix B.

The study analyses sentencing data for environmental offences finalised in the NSW Local Court for the period 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2013 (the study period). The study uses a larger data period of 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2013 (the trend period) for the purposes of showing medium-term trends in fines. The sentencing data analysed are for first-instance environmental offences in the Local Court. The data have not been corrected for (albeit rare) successful appeals to the LEC.

By way of background, Local Court sentencing data are initially collected on behalf of the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) by court registry staff.114 The data are supplied to the Judicial Commission for use in studies and for publication on the statistics component of JIRS.

As discussed above, environmental offences come before the Local Court in a number of ways. Given the utilisation of penalty notices by prosecution authorities referred to above, it can be inferred that the most common method is where a penalty notice has been issued and the alleged offender chooses to contest the matter in court. Prosecutors from the EPA and the NSW Department of Planning & Environment confirmed in recent discussions that most environmental offences which are dealt with by the Local Court are contested penalty notices. Other ways include where the prosecutor decides to proceed by way of a court attendance notice or where the prosecutor has initially issued a penalty notice, but decides to withdraw it and proceed by way of a court attendance notice.115 It was not possible to identify which of these categories each case fell within using data supplied by BOCSAR. Therefore these categories cannot be separately analysed.

Data are also not available for important sentencing factors relating to the offender and the circumstances in which offences were committed, including, for example, the matters that a court must consider in imposing a penalty under s 241 of the POEO Act,116 the offenders motive and subjective considerations such as an offenders means to pay,117 prior record and any assistance provided to authorities. As a result, the study cannot examine the relationship between these factors and the sentence imposed. Nor does it examine other sentencing factors such as plea, age or number of offences, due to the small number of cases in some of these categories.

The analysis is based on the principal offence for which an offender is sentenced. More specifically, where an offender has been sentenced for more than one offence in a single finalised court appearance, only the offence which attracts the highest penalty, in terms of the type and quantum of sentence, is included in the analysis. Accordingly, where multiple fines have been imposed on an offender, the highest individual fine is included in the analysis, and fines imposed for secondary offences are excluded.118 Additional orders119 which can attach to the principal offence in the sentencing exercise are not included in the data supplied by BOCSAR and therefore cannot be analysed.

If an offender has been sentenced in more than one finalised court appearance during the data period, the data include the sentence imposed for the principal offence in each finalised court appearance.

Method of classifying offences

Subject to the following, offences in the study are classified according to the specific provisions in the Act or regulation which create the offences. Section 125 of the EPA Act provides that a person who offends against any direction or prohibition under the Act or regulations is guilty of an offence. Generally, these offences are classified according to the further provisions which describe the nature of the contravention (for example, ss 76A(1)(a) and (b) of the EPA Act). However, where the only offence charged was an offence under s 125(1), the offence is classified as one committed under that provision.

In cases where the offence provision sets out a number of different ways in which the offence may be committed and the maximum penalty is the same for each of these, the contraventions are grouped under a single offence (for example, s 277 of the POEO Act).

Further, if an offence has been repealed and re-enacted in identical terms, the sentencing data for the offence under the repealed and re-enacted provision is combined.

Continuing offences

A continuing offence is set out in the specific statute creating the offence and is usually expressly referred to in the penalty provision for the offence. Section 242 of the POEO Act is a good example. It governs the prosecution of continuing offences under that Act.

Section 242 of the POEO Act provides that a person who is guilty of an offence because the person contravenes a requirement made by, or under, the Act or the regulations to do or cease to do something:

- continues, until the requirement is complied with and despite the fact that any specified period has expired or time has passed, to be liable to comply with the requirement, and

- is guilty of a continuing offence for each day the contravention continues.

This section applies to those provisions in the POEO Act and regulations which provide a specific penalty for a continuing offence, such as s 120(1) of the POEO Act.120 For a continuing offence under s 120(1), s 123 of the POEO Act provides for a further daily penalty not exceeding $120,000 in the case of a corporate offender and $60,000 in the case of an individual offender. Other environmental offences which contain specific penalties for continuing offences include ss 91(5), 97, 142A(1), 144(1) and 211(1) of the POEO Act. Further daily penalties of $110,000 are also provided for in s 126(1) of the EPA Act for contraventions of ss 76A(1)(a), (b), 76B, 121B and 125(1).

The sentencing data provided by BOCSAR does not identify continuing offences.121 As a consequence, where a penalty has been imposed on an offender for a continuing offence, these amounts are unavoidably combined with the penalty imposed for the offence. The fine imposed for one individual and one corporation in the study exceeded the maximum penalty for the offence. This was because a daily penalty was also imposed for continuing offences.122 In respect of the corporation, the penalty imposed also exceeded the jurisdictional maximum of the Local Court.

Increase in the Local Courts jurisdictional limit

Parliament has set a jurisdictional limit for the Local Court under each of the Acts under examination. As discussed above, in February 2012, the maximum monetary penalty that the Local Court can impose for an offence under the POEO Act increased from $22,000 to $110,000.

An issue arises as to whether the increased jurisdictional maximum applies to offences committed before the increase. One view is that unless otherwise provided, the increased jurisdictional maximum applies to all cases that come before the court forthwith. This is on the basis that it is a procedural reform relevant only to the (court) forum in which the charge can be prosecuted. In short, it does not expose the offender to a higher maximum penalty for an offence as is prohibited by s 19 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999. It simply affects where the offence may be prosecuted.

In order to ascertain whether the increase in the jurisdictional limit for the Local Court under the POEO Act had an effect on sentencing levels for these offences, it would be necessary to identify cases where a choice of forum had been made, that is, a decision had been made to prosecute a case in the Local Court rather than the LEC following the increase in the jurisdictional limit. This was not possible given the available data (including the fact that there were only a small number of cases which may notionally have been impacted), and could not be inferred.123 Further difficulties associated with continuing offences under the POEO Act, as discussed above, may also have undermined any analysis of this kind.

Increase in the penalty notice amount

On 2 March 2009, penalty notice amounts for certain offences under the EPA Act increased (for example, ss 76A(1)(a), (b) and 121B(1)).124 An issue arises as to whether the increase in the penalty notice amounts can apply to offences committed before the increase. Given the irrelevance of the prescribed amount of a penalty notice under the Fines Act when a matter is contested in court,125 it is unlikely this issue will be the subject of appellate consideration. However, there is an argument that, unless otherwise provided, the authority issuing a penalty notice should not apply a penalty notice increase to offences committed before the date of the increase. The principles against retrospectivity set out in the High Court decision of Rodway v The Queen,126 the spirit of s 19 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act127 and s 30(1)(d) of the Interpretation Act 1987 support such an argument. The latter section provides that the amendment or repeal of an Act or statutory rule does not affect any penalty incurred in respect of any offence arising under the Act or statutory rule and any such penalty may be imposed and enforced as if the Act or statutory rule had not been amended or repealed.

In order to ascertain whether the 2 March 2009 increase in the penalty notice amounts had an effect on sentencing levels, subject to the following, the data was separated into pre- and post-increase categories according to the date of the offence. In a small number of cases, it was apparent from the law part code128 used that the increased penalty notice amount had been applied to offences which pre-dated the increase. These cases were placed in the post-increase category.

Measures used in the analysis

The mean and the median are both used as measures of central tendency to describe a set of sentencing data (fines) with a single value that represents the middle or centre of its distribution.

The mean refers to the average fine. However, as the mean has the potential to be skewed by outliers where a few offenders receive heavy fines, it is not as useful as a measure of central tendency as the median. The median refers to the value of the fine where half of the cases lie above and half lie below that value (50th percentile).

The percentage of fines which fall within the middle 50% range of values is also shown. The lower limit of this range is set at the first quartile (25th percentile) and the upper limit is set at the third quartile (75th percentile). This range shows the spread of values near the centre.

Findings

There were 2,413 offenders sentenced for at least one environmental offence in the Local Court during the study period. These offenders committed a total of 4,287 offences of which 3,052 were environmental offences. The vast majority of environmental offences were prosecuted under the POEO Act or regulations made under that Act (43.0%) or the EPA Act (40.1%). Individual offenders committed 79.4% of all environmental offences, while corporations committed 20.6%.

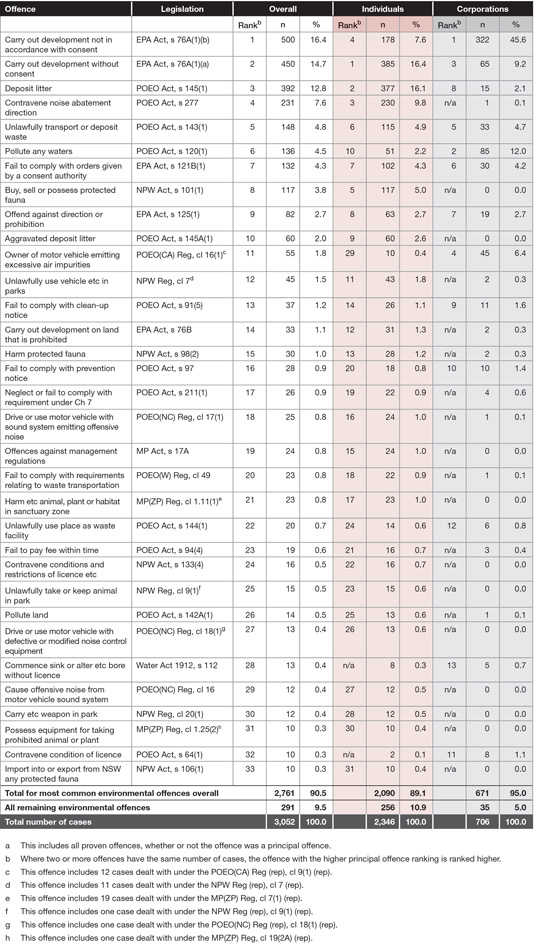

Appendix C shows the 33 most common proven environmental offence groupings (principal and secondary offences) dealt with in the Local Court in the study period where there were at least 10 offences overall (individuals and corporations). The top three offences accounted for 44.0% of all environmental offences: carry out development not in accordance with consent under s 76A(1)(b) of the EPA Act was the most common (16.4%); followed by carry out development without consent under s 76A(1)(a) of the EPA Act (14.7%); and deposit litter under s 145(1) of the POEO Act (12.8%).

While individuals make up most of the offenders in each offence (including all of the offenders in 11 offences and over 90% of the offenders in eight offences), corporations are over-represented in four offences: owner of motor vehicle emitting excessive air purities under cl 16(1) of the POEO(CA) Reg (81.8%); contravene condition of licence under s 64(1) of the POEO Act (80.0%); carry out development not in accordance with consent under s 76A(1)(b) of the EPA Act (64.4%); and pollute any waters under s 120(1) of the POEO Act (62.5%).

The environmental offence was the principal offence in the sentencing exercise for 2,053 offenders (85.1%). The vast majority of these offenders (83.7% or 1,719 offenders) were sentenced for only one environmental offence. Individual offenders committed 75.8% of the principal offences, while corporations committed 24.2%.

The following analysis relates to the principal offence only.

Penalties imposed

In any given case, the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act, the Fines Act, the common law and the specific statute creating the environmental offence provide the framework within which a court determines the sentence to be imposed. The Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act sets out various penalty options for the courts.

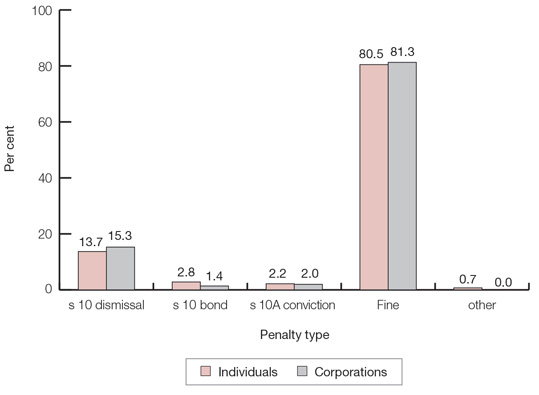

Figure 1 outlines the distribution of penalties for environmental offences in the Local Court for the study period.

Figure 1: Distribution of penalty types for environmental offences in the NSW Local Court in the study period (principle offence only)

Overwhelmingly, a fine was the most common penalty imposed for the principal offence for both individuals (80.5%) and corporations (81.3%).129 This is not surprising given that fines are almost invariably the maximum sentence that a court is entitled to impose.

Other penalty types imposed on the remaining offenders were as follows:

- s 10 dismissal (offence proven without recording a conviction) was imposed for 13.7% of individuals and 15.3% of corporations

- s 10 bond (offence proven without conviction but with conditions during the bond period) was imposed for 2.8% of individuals and 1.4% of corporations

- s 10A conviction with no further penalty was imposed for 2.2% of individuals and 2.0% of corporations

- s 9 bond (conviction recorded without supervision) was imposed for six individuals (0.4%)

- a community service order (s 8), suspended sentence (s 12) or intensive correction order (s 7) was imposed on three individual offenders respectively

- full-time imprisonment (ss 5, 4446) was imposed on two individuals.

The references to sections in the above bullet points are to sections of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act.

Overall level of fines imposed

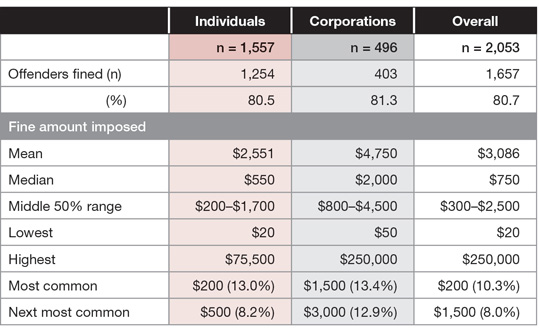

Table 1 provides an overview of the fines that were imposed for environmental offences in the study period.

Table 1: Fine imposed for environmental offences in the NSW Local Court in the study period (principal offence only)

For individuals, the median fine was $550 and 62.6% of fines were in the middle 50% range of $200 to $1,700. The mean fine was $2,551 and common fines were $200 and $500 (imposed on 13.0% and 8.2% respectively). The highest fine was $75,500 for an offence of fail to comply with clean-up notice under s 91(5) of the POEO Act. As mentioned above, the fine for the offence included a further daily penalty amount for a continuing offence.130Putting this case to one side, three individuals received a fine of $75,000 for offences under the EPA Act.

For corporations, the median fine was $2,000 and 51.1% of fines were in the middle 50% range of $800 to $4,500. The mean fine was $4,750 and common fines were $1,500 and $3,000 (imposed on 13.4% and 12.9% respectively). The highest fine was $250,000 for an offence of neglect or fail to comply with requirement under Ch 7 contrary to s 211(1) of the POEO Act.131 The fine for the offence included a further daily penalty amount for a continuing offence.

Clearly, the overall level of fines for corporations was higher than individuals and the spread of fines was greater.

Most common environmental offences

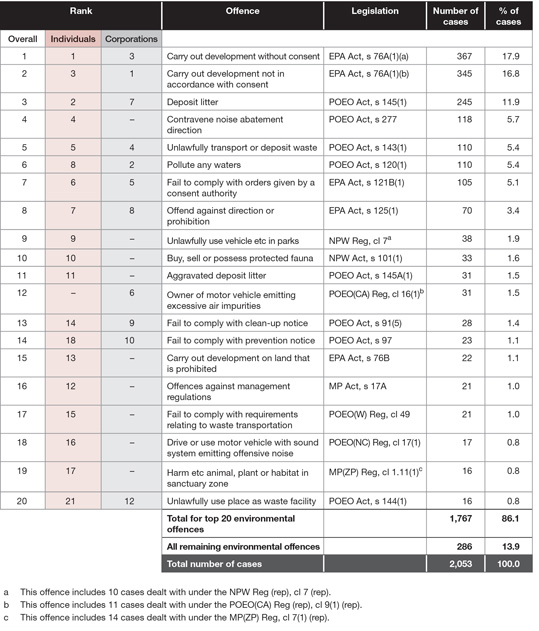

Table 2 shows the 20 most common environmental offences dealt with in the Local Court in the study period. It also shows the offence rankings for individuals and corporations.133 Tables 3 and 4 show the number of cases for the most common environmental offences committed by individuals and corporations respectively.134 Where two or more offences have the same number of cases, the offence with the higher ranking as shown in Appendix C is ranked higher.

The 20 most common environmental offences comprised 86.1% (1,767 cases) of all environmental offences.

Eleven of these 20 offences were offences under the POEO Act or the regulations made under that Act, and five were offences under the EPA Act. Two offences under the EPA Act comprised just over a third (34.7%) of all environmental offences: carry out development without consent under s 76A(1)(a) of the EPA Act; and carry out development not in accordance with consent under s 76A(1)(b) of the EPA Act.

The most common offence overall was carry out development without consent, comprising 17.9% (367 cases) of all environmental offences. The offence ranked first for individuals (20.1% or 313 cases) and third for corporations (10.9% or 54 cases).

The closely-related offence of carry out development not in accordance with consent ranked second overall. This offence comprised 16.8% (345 cases) of all environmental offences. It was the most common offence committed by corporations, accounting for 41.7% of all environmental offences for corporations. It ranked first by a high margin, with 207 cases, compared to the next most common offence for corporations of pollute any waters under s 120(1) of the POEO Act, which had 66 cases. The offence of carry out development not in accordance with consent ranked third for individuals, comprising 8.9% (138 cases) of all environmental offences committed by individuals.

The offence of deposit litter under s 145(1) of the POEO Act ranked third overall and comprised 11.9% (245 cases) of all environmental offences. It was the second most common offence for individuals (14.8% or 230 cases) and ranked seventh for corporate offenders (3.0% or 15 cases). The related offence of aggravated deposit litter under s 145A of the POEO Act ranked 11th overall.

The offence of contravene noise abatement direction under s 277 of the POEO Act comprised 5.7% (118 cases) of all environmental offences, ranking fourth overall. It also ranked fourth for individual offenders (7.5% or 117 cases). Only one corporate offender committed this offence.

The offence of unlawfully transport or deposit waste under s 143(1) of the POEO Act ranked fifth overall and comprised 5.4% (110 cases) of all environmental offences. It represented 5.5% of all environmental offences committed by individuals (85 cases) and 5.0% committed by corporations (25 cases), ranked fifth and fourth respectively. The related offence of fail to comply with requirements relating to waste transportation under cl 49 of the POEO(W) Reg ranked 17th overall.

The offence of pollute any waters under s 120(1) of the POEO Act ranked sixth overall, comprising 5.4% (110 cases) of all environmental offences. That offence ranked second for corporations (13.3% or 66 cases) and eighth for individuals (2.8% or 44 cases).

The offence of fail to comply with orders given by a consent authority under s 121B(1) of the EPA Act ranked seventh overall and comprised 5.1% (105 cases) of all environmental offences. That offence ranked fifth for corporations (4.8% or 24 cases) and sixth for individuals (5.2% or 81 cases).

The offence of offend against direction or prohibition under s 125(1) of the EPA Act ranked eighth overall, comprising 3.4% (70 cases) of all environmental offences.135 It ranked seventh for individuals (3.6% or 56 cases) and eighth for corporations (2.8% or 14 cases).

After the eighth-ranked offence, the number of cases falls considerably. Offences ranking ninth to 20th made up only 14.5% of all environmental offences.

Table 2: Most common environmental offences (principal offence only) in the NSW Local Court in the study period

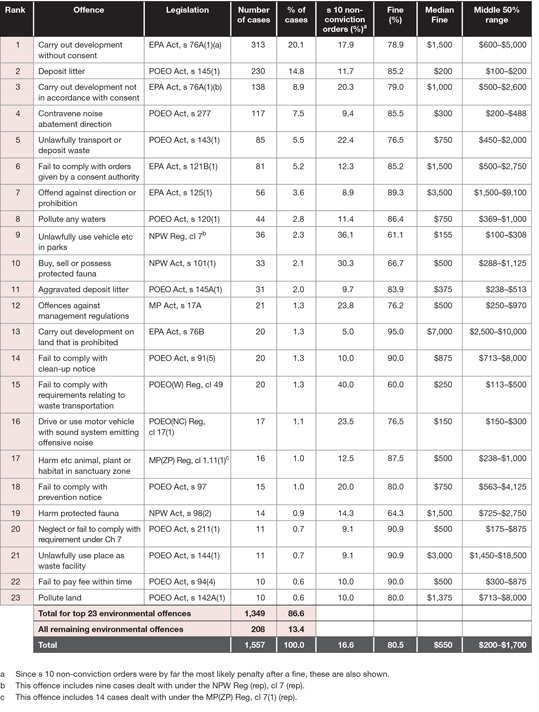

Table 3: Level of fines imposed for the most common environmental offences committed by individuals (principle offence only) in the NSW Local Court in the study period

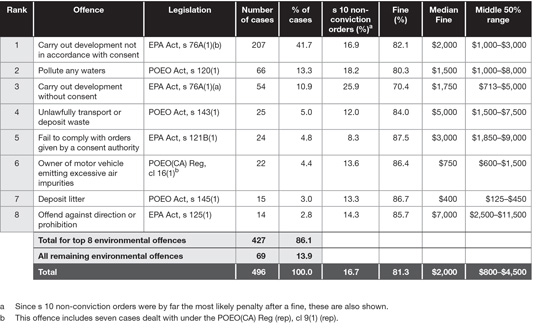

Table 4: Level of fines imposed for the most common environmental offences committed by corporations (principal offence only) in the NSW Local Court in the study period

Level of fines imposed for the most common environmental offences

In addition to showing the number of cases for the most common environmental offences committed by individuals and corporations respectively (at least 10 cases), Tables 3 and 4 show the level of fines imposed on these offenders. Since s 10 non-conviction orders were by far the most likely penalty after a fine, these are also shown. A relatively low rate of fines for an offence usually indicates a relatively high rate of s 10 non-conviction orders, mostly s 10 dismissals, for that offence.

For individuals, there were 23 offences with at least 10 cases. The offence of carry out development on land that is prohibited under s 76B of the EPA Act had the highest rate of fines (95.0%) and the highest median fine ($7,000). The next most heavily fined offences were offend against direction or prohibition under s 125(1) of the EPA Act (median fine $3,500), followed by unlawfully use place as waste facility under s 144(1) of the POEO Act (median fine $3,000).

Three offences recorded relatively low rates of fines and high rates of s 10 non-conviction orders for individuals: fail to comply with requirements relating to waste transportation under cl 49 of the POEO(W) Reg (60.0% and 40.0% respectively); unlawfully use vehicle etc in parks under cl 7 of the NPW Reg (61.1% and 36.1% respectively); and buy, sell or possess protected fauna under s 101(1) of the NPW Act (66.7% and 30.3% respectively). The first two of those offences also incurred relatively low median fines ($250 and $155 respectively). However, the lowest median fine was observed for drive or use motor vehicle with sound system emitting offensive noise under cl 17(1) of the POEO(NC) Reg ($150). The third lowest median fine was imposed for deposit litter under s 145(1) of the POEO Act ($200).

For corporations, there were eight offences with at least 10 cases. The offence of offend against direction or prohibition under s 125(1) of the EPA Act was the most heavily fined offence (median fine $7,000). This was followed by the offence of unlawfully transport or deposit waste under s 143(1) of the POEO Act (median fine $5,000).

On the other hand, the least heavily fined offence was deposit litter under s 145(1) of the POEO Act (median fine $400). This was followed by the offence of owner of motor vehicle emitting excessive air impurities under cl 16(1) of the POEO(CA) Reg (median fine $750). The lowest rate of fine and highest use of s 10 non-conviction orders was observed for carry out development without consent under s 76A(1)(a) of the EPA Act (70.4% and 25.9% respectively).

Fines imposed for the seven most common offences

The following section analyses the seven most common offences, which account for over two-thirds (68.2%) of all environmental offences. These seven offences also include the top five offences for both individuals and corporations.

Tables 5 to 11 show the fines imposed for these offences. Findings are presented, where relevant, to show the relationship, if any, between penalty notice amounts for offences and the fines imposed. The analysis also examines the impact of the 2009 increase in penalty notice amounts for certain offences under the EPA Act.

The statistics presented in these tables are reported as follows:

- the mean and median fines, and the proportion of cases which received a fine above, at, or below the penalty notice amount are shown where there were at least five cases

- the middle 50% range of fines is shown where there were at least 10 cases

- the next most common fine is shown where there were at least four cases of that amount.

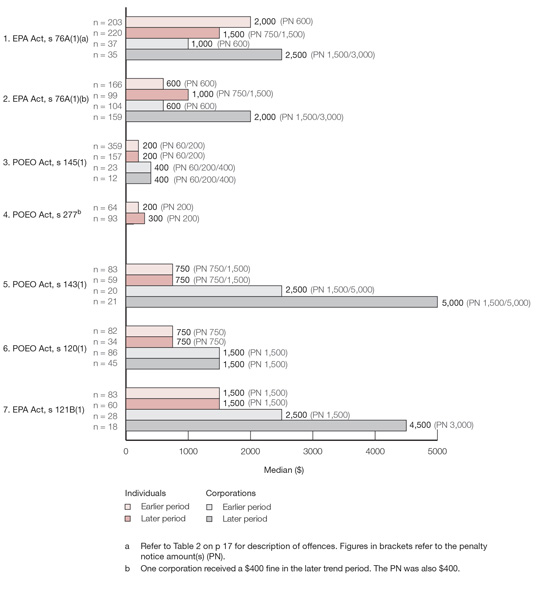

Figures 2 to 7 show trends in median fines for the most common offences in the trend period where there were at least 10 individual or corporate offenders in at least seven consecutive years.

Due to the small number of cases in a given year for some offences, further analysis presented in Figure 8 shows trends in median fines by reference to two equal time periods: the first period includes fines imposed from 1 January 2005 to 30 June 2009 (earlier trend period); and the second period includes fines imposed from 1 July 2009 to 31 December 2013 (later trend period). This breakdown allows comparisons to be made not only between individuals and corporations, but also across each of the seven most common offences.

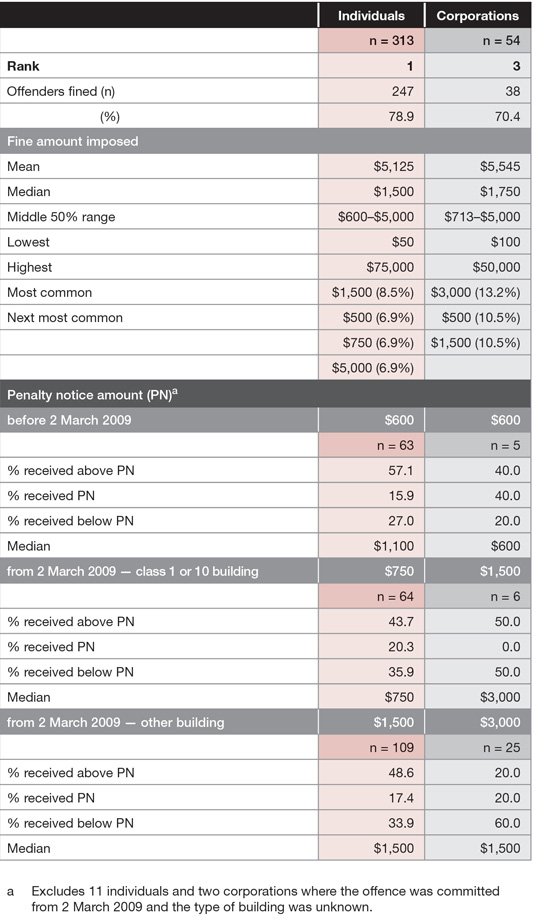

1. Carry out development without consent

EPA Act, s 76A(1)(a)

Maximum penalty: $1,100,000 + further daily penalty of $110,000136

Jurisdictional maximum in Local Court: $110,000137

During the study period, individuals accounted for the vast majority (85.3%) of offences under s 76A(1)(a) of the EPA Act. Over three-quarters of individuals (78.9%) and over two-thirds of corporations (70.4%) received a fine.

Table 5 shows the fines imposed for this offence. The highest fine received by an individual was $75,000 and $50,000 for a corporation. The median fine for individuals was $1,500 and was marginally higher for corporations ($1,750). The middle 50% range of fines for individuals ($600$5,000) and corporations ($713$5,000) was also similar: 53.8% of individuals and 55.2% of corporations received a fine in the middle 50% range.

Table 5: Fines imposed in the study period carry out development without consent: EPA Act, s 76A(1)(a)

Penalty notice amount

The penalty notice amount for this offence increased on 2 March 2009 for both individuals and corporations.138 Before 2 March 2009, it was $600 for both individuals and corporations. From that date it increased to $750 for individuals and $1,500 for corporations for a class 1 or 10 building. Where the offence was committed in any other building, the penalty notice amount increased to $1,500 for individuals and $3,000 for corporations. In order to examine the relationship between the fines imposed and the corresponding penalty notice amounts for these offences, the cases have been classified under the following offence categories: before 2 March 2009 offences, from 2 March 2009 class 1 or 10 building offences, and from 2 March 2009 any other building offences.

It can be seen from Table 5, from 2 March 2009 any other building offences were more common for both individuals and corporations, accounting for 63.0% and 80.6% of cases respectively.

Less than one in five (18.0%) offenders received a fine equal to the corresponding penalty notice amount for the offence (17.8% of individuals and 19.4% of corporations). Nevertheless, as Table 5 shows, the median fines for individuals matched the penalty notice amounts for both offence categories from March 2009. Although this was not the case for corporations, the number of cases for class 1 or 10 building offences was small. For any other building offences, there was no difference in the median fine imposed for individuals and corporations (both $1,500), even though the penalty notice amount for corporations was $3,000 (twice as much as it was for individuals).

For before 2 March 2009 offences, the median fine for individuals ($1,100) was higher than the corresponding penalty notice amount. Once again, the number of cases for corporations was too small to make any meaningful comparisons.

Trend period

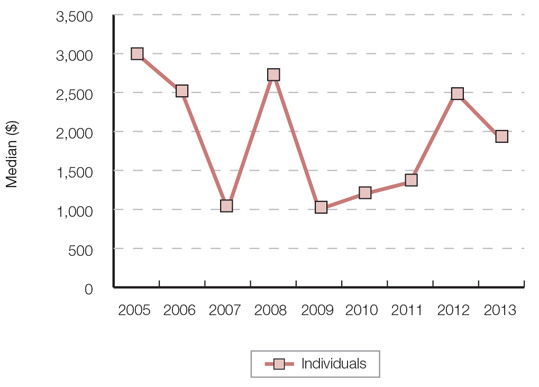

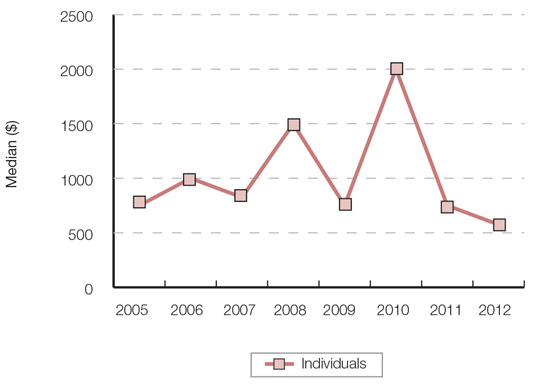

Figure 2 shows that the median fine for individuals fluctuated between $1,000 and $3,000 over the trend period. The highest median fine was $3,000 in 2005 and the lowest median fine was $1,000 in 2007 and 2009. However, there has been a general upward trend in median fines for individuals since 2009.

Figure 2: Median fines for the trend period carry out development without consent: EPA Act, s 76A(1)(a)

A trend graph is not shown for corporations as there were insufficient cases in some of the years in the trend period.

2. Carry out development not in accordance with consent

EPA Act, s 76A(1)(b)

Maximum penalty: $1,100,000 + further daily penalty of $110,000139

Jurisdictional maximum in Local Court: $110,000140

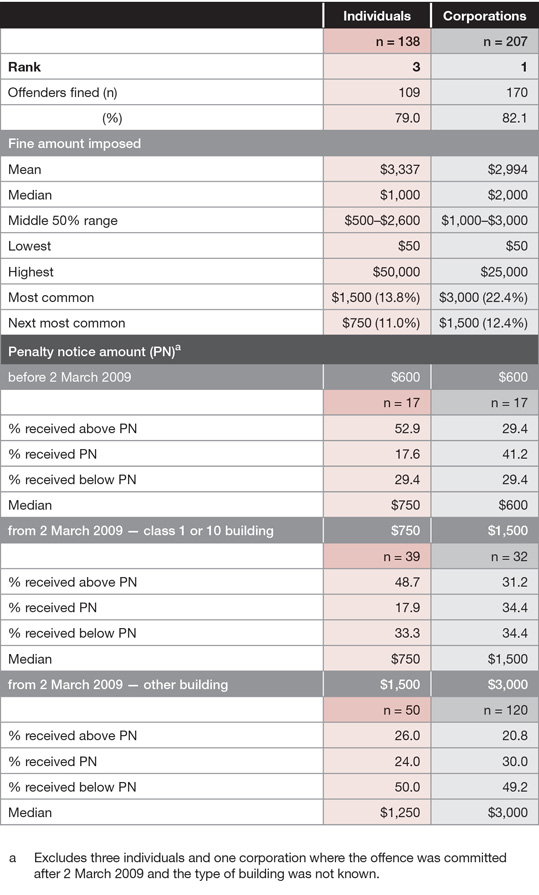

The offence under s 76A(1)(b) of the EPA Act was by far the most common offence committed by corporations during the study period, with these offenders accounting for 60.0% of cases. Over three-quarters of individuals (79.0%) and 82.1% of corporations received a fine.

Table 6 shows the fines imposed for this offence. The highest fine received by an individual was $50,000 and $25,000 for a corporation. The median fine for individuals was $1,000 and 55.9% of fines were in the middle 50% range of $500 to $2,600. For corporations, the median fine was $2,000 and 56.5% of fines were in the middle 50% range of $1,000 to $3,000.

Table 6: Fines imposed in the study period carry out development not in accordance with consent: EPA Act, s 76A(1)(b)

Penalty notice amount

Given that the penalty notice amount for this offence increased on 2 March 2009 for both individuals and corporations as for the first ranked offence under s 76A(1)(a) of the EPA Act, the cases have been classified under the same offence categories.

As with the first ranked offence, from 2 March 2009 any other building offences were more common for both individuals and corporations, accounting for 56.2% and 78.9% of cases respectively.

For corporations, the median fine was the same as the penalty notice amount corresponding to each category of offence: $600 before 2 March 2009 offences; and $1,500 and $3,000 from 2 March 2009 class 1 or 10 building offences and any other building offences respectively. This is unsurprising given that almost a third (32.0%) of corporations received a fine equal to the penalty notice amount.

While only 20.8% of individuals received a fine equal to the corresponding penalty notice amount, the median fine for each category of offence was close to, and for one category, the same as, the corresponding penalty notice amount ($750, $750 and $1,250 respectively).

Trend period

There has been a significant change in the proportion of cases that were committed by individuals and corporations during the trend period. In the four years prior to the study period (1 January 2005 to 31 December 2008), corporations accounted for 37.3% of cases compared with 60.0% of cases in the study period. Corporations first appeared in greater numbers in 2010 where they comprised 55.3% of the cases for this offence, reaching 70.2% of the cases in 2013.

Figure 3 shows that from 2009, the median fines generally increased for individuals and corporations. This again may be partially attributed to the March 2009 increases in the penalty notice amount. The fall in the median fine for individuals in 2013 is inexplicable, although it is noted that there were only a small number of cases compared with other years.

Figure 3: Median fines for the trend period carry out development not in accordance with consent: EPA Act, s 76A(1)(b)

3. Deposit litter

POEO Act, s 145(1)

Maximum penalty: $2,200

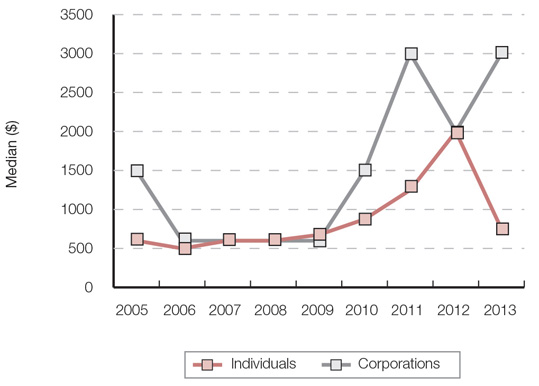

During the study period, individuals committed the overwhelming proportion of offences under s 145(1) of the POEO (93.9%). The vast majority of individuals and corporations received a fine (85.2% and 86.7% respectively).

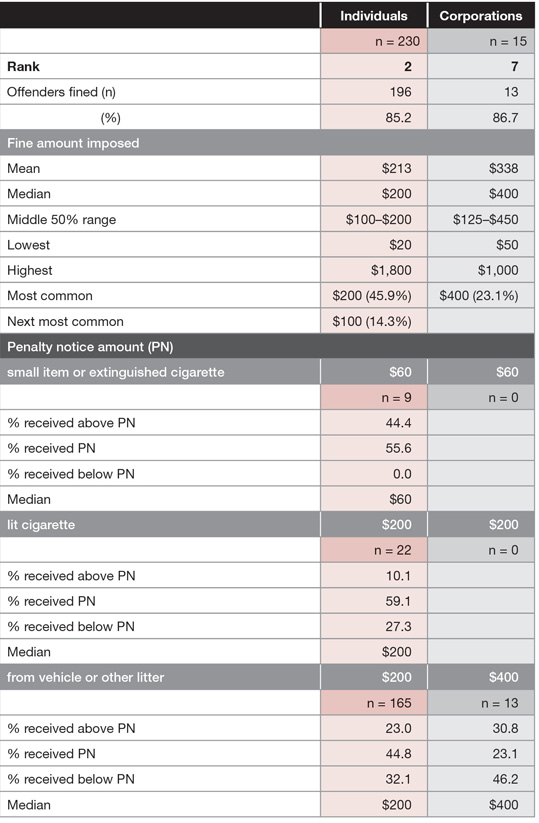

Table 7 shows the fines imposed for this offence. The highest fine received by an individual was $1,800 and $1,000 for a corporation. This offence received the lowest fine of any offence ($20 for individuals and $50 for corporations). The median fine for individuals was $200, which was also the most common fine by far imposed on 45.9% of individuals. Almost two-thirds (65.8%) of individuals received a fine in the middle 50% range of $100 to $200. The median fine for corporations was $400 and 61.5% of fines were in the middle 50% range of $125 to $450.

Table 7: Fines imposed in the study period deposit litter: POEO Act, s 145(1)

As expected, the median fine for this offence was less than the median fine for the offence of aggravated deposit litter under s 145A of the POEO Act. For individuals, it was $200 for this offence compared with $375 for the aggravated offence.

Penalty notice amount

The penalty notice amount for this offence varied depending on the category of littering. During the study period, the penalty notice amount was $60 for small item141 or extinguished cigarette and $200 for lit cigarette. It was $200 for from vehicle or other litter for individuals and $400 for corporations.142 In order to examine the relationship between the fines imposed and the corresponding penalty notice amounts for these offences, the cases have been classified according to these offence categories.

The most common littering offence for both individuals and corporations was from a vehicle (71.4% and 69.2% respectively).

As Table 7 shows, the median fine was higher for categories of littering that attract higher penalty notice amounts. In fact, the median fine for each category was the same as the corresponding penalty notice amount. This was clearly evident in the proportion of individuals who received a fine equal to the corresponding penalty notice amount (55.6% for small item or extinguished cigarette; 59.1% for lit cigarette; and 44.8% where the litter was from vehicle or other litter).

Trend period

The number of cases for individuals has dramatically fallen for this offence over the trend period from 134 cases in 2005 to just 18 cases in 2013.

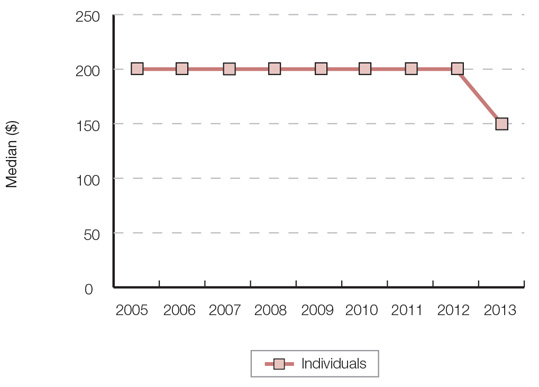

Figure 4 shows that the median fine for individuals was $200 for each year of the trend period except for 2013. This may be attributed to the fact that 96.5% of the individual offenders fined involved littering for which the penalty notice amount was $200.

A trend graph is not shown for corporations as there were insufficient cases in all but one of the years in the trend period.

Figure 4: Median fines for the trend period deposit litter: POEO Act, s 145(1)

4. Contravene noise abatement direction

POEO Act, s 277

Maximum penalty: $3,300

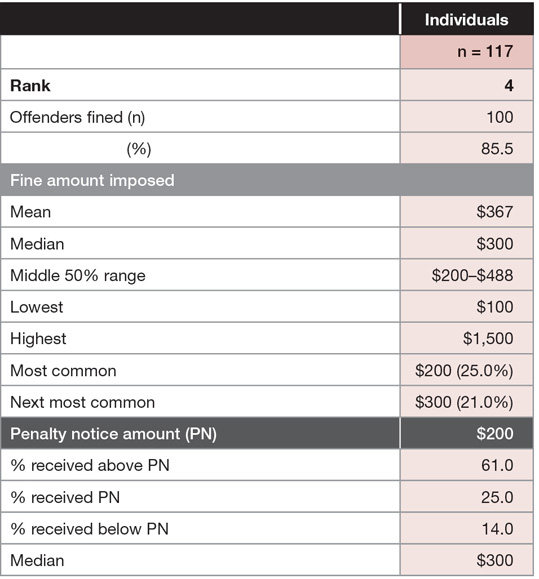

During the study period, individuals committed all but one of the offences under s 277 of the POEO Act. Of these, 85.5% received a fine, as did the single corporate offender.

Table 8 shows the fines imposed on individuals for this offence. For individuals, the median fine was $300, and 61.0% of fines were in the middle 50% range of $200 to $488. The highest fine was $1,500. The corporate offender was fined $400.

Penalty notice amount

The penalty notice amount for this offence for individuals was $200 and $400 for corporations. As Table 8 shows, a quarter (25.0%) of individuals received a fine equal to the corresponding penalty notice amount, as did the corporate offender. Most (61.0%) individuals, however, received a fine greater than the penalty notice amount.

Table 8: Fines imposed in the study period contravene noise abatement direction: POEO Act, s 277

Trend period

Figure 5 shows that for offences under s 277 of the POEO Act the median fine has increased since 2009 from $200 to $300 or more.

Figure 5: Median fines for the trend period contravene noise abatement direction: POEO Act, s 277

As there was only one corporate offender, no trend graph is shown for corporations.

5. Unlawfully transport or deposit waste

POEO Act, s 143(1)

Maximum penalty: $1,000,000 (corporation); $250,000 (individual)

Jurisdictional maximum in Local Court:143

$22,000 (to 5 February 2012); $110,000 (from 6 February 2012)

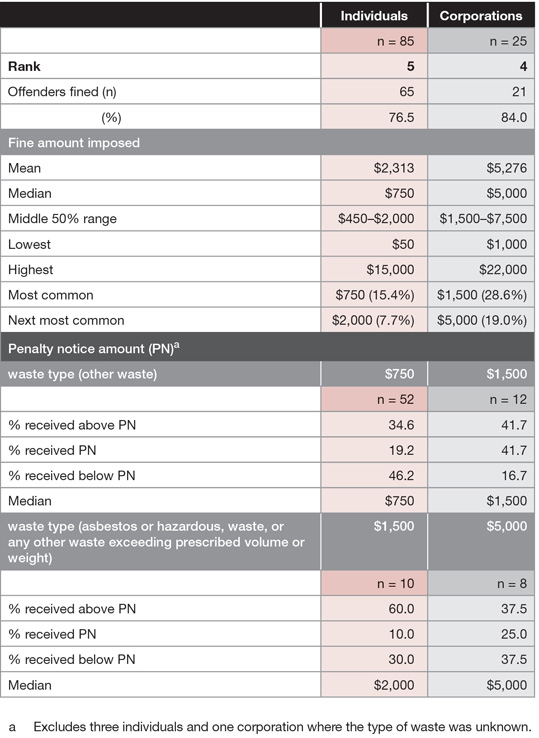

During the study period, individuals committed the majority (77.2%) of the offences under s 143(1) of the POEO Act. Over three-quarters (76.5%) of individuals and 84.0% of corporations received a fine.

Table 9 shows the fines imposed for this offence. The highest fine received by an individual was $15,000 and $22,000 for a corporation. For individuals, the median fine was $750 and 56.9% of fines were in the middle 50% range of $450 to $2,000. For corporations, the median fine was $5,000 and 57.2% of fines were in the middle 50% range of $1,500 to $7,500.

Table 9: Fines imposed in the study period unlawfully transport or deposit waste: POEO Act, s 143(1)

Penalty notice amount

The penalty notice amount for this offence varied depending on the type of waste. During the study period, the penalty notice amounts for individuals and corporations were $750 and $1,500 for other waste and $1,500 and $5,000 for asbestos or hazardous waste, or any other waste exceeding prescribed volume or weight respectively.144 In order to examine the relationship between the fines imposed and the corresponding penalty notice amounts, the cases have been classified according to these offence categories.

Offences involving other waste were the more common for both individuals and corporations, accounting for 83.9% and 60.0% of cases respectively.

The proportion of individuals who received a fine equal to the corresponding penalty notice amount was not high (17.7%). Nevertheless, as Table 9 shows, the median fine ($750) was the same as the corresponding penalty notice amount for other waste, and 33.3% higher ($2,000) than the corresponding penalty notice amount for asbestos or hazardous waste, or any other waste exceeding prescribed volume or weight. For corporations, the median fine was the same as the corresponding penalty notice amount for both categories of offence ($1,500 and $5,000 respectively). This is unsurprising given that just over a third (35.0%) of corporations received a fine equal to the corresponding penalty notice amount for the offence.

Trend period

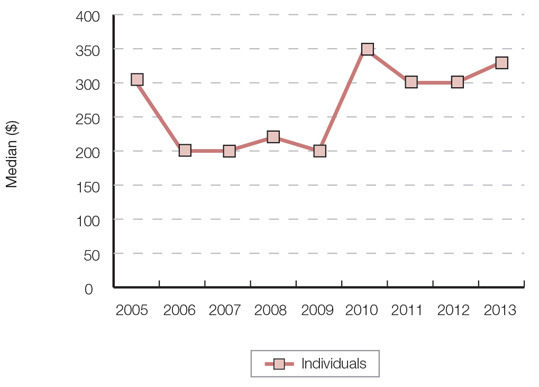

Figure 6 shows that the median fine for individuals fluctuated above and below $1,000 over the trend period. No discernible trend is observed and the increase in the jurisdictional limit of the Local Court does not appear to have had any effect on the trend in median fines for this offence. Although there were only nine cases in 2013, the median fine ($650) was still low.

Figure 6: Median fines for the trend period unlawfully transport or deposit waste; POEO Act, s 143(1)

Figure 6 does not plot the median fine for 2013 as there were insufficient cases in that year. A trend graph is not shown for corporations as there were insufficient cases in each of the years in the trend period.

6. Pollute any waters

POEO Act, s 120(1)

Maximum penalty: $1,000,000 + further daily penalty of $120,000 (corporation); $250,000 + further daily penalty of $60,000 (individual)145

Jurisdictional maximum in Local Court:146

$22,000 (to 5 February 2012); $110,000 (from 6 February 2012)

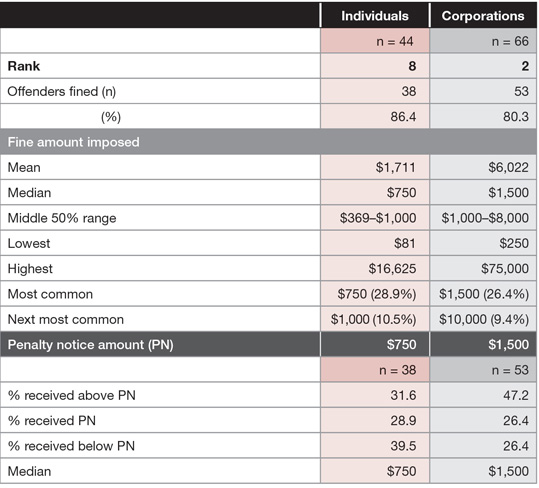

The offence under s 120(1) of the POEO Act was the second most common offence committed by corporations with these offenders accounting for 60.0% of cases during the study period. The majority of individuals (86.4%) and corporations (80.3%) received a fine.

Table 10 shows the fines imposed for this offence. The highest fine received by an individual was $16,625 and $75,000 for a corporation. The latter fine was imposed following the increase in the jurisdictional limit of the Local Court. The median fine for individuals was $750 and 55.2% of fines were in the middle 50% range of $369 to $1,000. For corporations, the median fine was $1,500 and 56.6% of fines were in the middle 50% range of $1,000 to $8,000.

Table 10: Fines imposed in the study period pollute any waters: POEO Act s 120(1)

Penalty notice amount

As Table 10 shows, the median fine was equal to the corresponding penalty notice amount for the offence for both individuals ($750) and corporations ($1,500).147 Just over a quarter of offenders received a fine equal to the corresponding penalty notice amount (28.9% and 26.4% for individuals and corporations respectively). However, almost half (47.2%) of corporations received a fine greater than the corresponding penalty notice amount.

Trend period

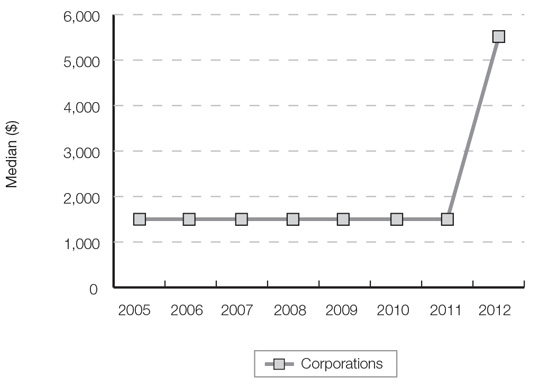

Since 2007, the number of cases for both individuals and corporations has noticeably fallen for this offence. For corporations it has almost halved, from an average of 25.7 cases per year from 2005 to 2007 to an average of 13.3 cases per year from 2008 to 2013. For individuals it has more than halved from an average of 25.7 cases per year from 2005 to 2007 to an average of 12.8 cases per year from 2008 to 2011, and to an average of just 5 cases per year from 2012 to 2013. Figure 7 shows that for offences under s 120(1) of the POEO Act, the median fine from 2005 to 2011 remained steady at $1,500 for corporate offenders. As mentioned above, this amount was equal to the corresponding penalty notice amount for corporations. There was, however, a sharp increase in the median fine in 2012 to $5,500. Although there were only nine cases in 2013, the median fine has increased further to $10,000. The increase may be partly attributable to the increase in the jurisdictional limit of the Local Court.

Figure 7: Median fines for the trend period pollute any waters: POEO Act, s 120(1)

Figure 7 does not plot the median fine amount for 2013 as there were insufficient cases in that year. A trend graph is not shown for individuals as there were insufficient cases in some of the later years in the trend period.

7. Fail to comply with orders given by a consent authority

EPA Act, s 121B(1)

Maximum penalty: $1,100,000 + further daily penalty of $110,000148

Jurisdictional maximum in Local Court: $110,000149

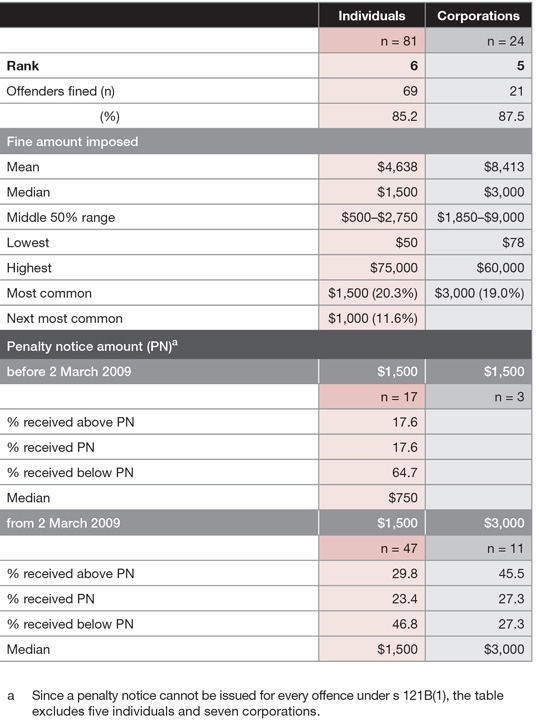

Individuals committed most of the offences under s 121B(1) of the EPA Act (77.1%) during the study period. The vast majority of individuals (85.2%) and corporations (87.5%) received a fine.

Table 11: Fines imposed in the study period fail to comply with orders given by consent authority: EPA Act, s 121B(1)

Table 11 shows the fines imposed for this offence. The highest fine received by an individual was $75,000 and $60,000 for a corporation. The median fine for individuals was $1,500 and 53.7% of fines were in the middle 50% range of $500 to $2,750. For corporations, the median fine was $3,000 and 52.4% of fines were in the middle 50% range of $1,850 to $9,000.

Penalty notice amount

On 2 March 2009, the penalty notice amount for this offence increased from $1,500 to $3,000 for corporations (it remained unchanged for individuals at $1,500).150 The number of cases for corporations in the period before the increase was too small to make comparisons. However, as Table 11 shows, after the increase, the median fines for offences which could attract a penalty notice were equal to the corresponding penalty notice amounts for both corporations and individuals.151 Despite the fact that there was no change in the penalty notice amount for individuals, the median fine has doubled from $750 for offences committed before 2 March 2009 to $1,500 for offences committed after 2 March 2009. This finding, however, is not supported in either analysis over the trend period (see below and Figure 8).

Trend period

Although there is no trend graph for this offence, there were a sufficient number of cases for individuals in seven (non-consecutive) years of the trend period. An examination of the fines imposed in those years revealed that the median fine in 2009 was unusually low, which could explain the low median fine observed above for offences committed before 2 March 2009 by individuals. This is because the majority (70.6%) of offences in this category were, as expected, sentenced in 2009.

Further analysis of median fines imposed over the trend period for the seven most common offences

The trends in median fines in the preceding analysis were based on yearly statistics. Since the number of cases for the seven most common offences varied greatly, as did the number of cases for individual and corporate offenders:

- only one of these offences had sufficient numbers to show a trend graph for both individuals and corporations

- five offences had sufficient numbers to show a trend graph for either individuals or corporations

- one offence did not have sufficient numbers to show a trend graph for either individuals or corporations.

In order to better illustrate similarities and differences between individuals and corporations, and to make further comparisons between the seven most common offences, the 9-year trend period was divided into two equal time periods:

- fines imposed from 1 January 2005 to 30 June 2009 (earlier trend period)

- fines imposed from 1 July 2009 to 31 December 2013 (later trend period).

The later trend period therefore includes most of the cases in the study period.

Figure 8: Median fines for the trend period (earlier or later) for the seven most common offencesa

Figure 8 shows the median fines for each of the seven most common offences for the earlier and later trend periods with a breakdown for individuals and corporations (comprising a total of 26 offence groupings).152 The number of cases and the corresponding penalty notice amount(s) are also shown.

Similarities and differences between individual and corporate offenders

- For corporations, the two offences that attracted the highest median fines were unlawfully transport or deposit waste (POEO Act, s 143(1)) and fail to comply with orders given by a consent authority (EPA Act, s 121B(1)). For individuals, the highest median fines were for the offences of carry out development without consent (EPA Act, s 76A(1)(a)) and fail to comply with orders given by a consent authority.

- The lowest median fine for both individuals and corporations was observed for the offence of deposit litter (POEO Act, s 145(1)). The offence of contravene noise abatement direction (POEO Act, s 277) also recorded a low median fine for individuals.

- Corporations generally received higher median fines than individuals. The only time corporations recorded a lower median fine was during the earlier trend period for the offence of carry out development without consent. Interestingly, the only other time corporations did not record a higher median fine was also during the earlier trend period for the related offence of carry out development not in accordance with consent (EPA Act, s 76A(1)(b)).

Similarities and differences between earlier and later trend periods

- The median fines imposed on corporations were higher in the later trend period for four offences and the same for two offences. The offences carry out development without consent followed by the related offence of carry out development not in accordance with consent had the largest percentage increase. Significant increases were also observed for the offence of unlawfully transport or deposit waste and fail to comply with orders given by a consent authority.

- For individuals, the median fines imposed in the later trend period were higher for two offences, the same for four offences and lower for one offence. The largest percentage increase in the median fine was observed for carry out development not in accordance with consent followed closely by contravene noise abatement direction. The decrease in the median fine occurred for the offence of carry out development without consent.

Relationship with penalty notice amounts