Navigating the Bail Act 2013

Introduction

Judicial officers make decisions concerning bail every day — on multiple occasions in the one day in the context of busy and varied court lists. In the Local Court in particular, these important decisions are frequently made on the basis of the limited information available at the early stages of the criminal process and within tight time frames.

A key feature of the Bail Act 2013* (“the Act”) is a risk-management based approach to bail decision-making. The statutory provisions governing bail are complex and require a considered and careful approach. Underlying the provisions is the important principle that an accused person, who is presumed to be innocent, is not to be punished before conviction.1 Judicial officers making bail decisions must therefore strike a balance between the difficult task of assessing future risk on the one hand and the presumption of innocence and the right of an accused person to be at liberty on the other.

The aim of this Sentencing Trends & Issues paper is to provide judicial officers and legal practitioners with a concise guide to the bail process and to supplement the content in the Local Court Bench Book. It provides a brief history of the Act, sets out the legislative provisions governing bail decisions, including those relating to jurisdiction, and discusses the procedural and evidential issues and the tests to be applied. It also summarises the relevant legal principles distilled from the case law. Bail decisions generally do not have precedential value because, more than in any other area of the criminal law, each decision involves an evaluative judgment based on the interplay of a multitude of factors particular to an individual case. In relation to this, of the practice of referring a bail court to individual bail judgments, RA Hulme J in DPP (NSW) v Zaiter,2 observed:

Bail decisions involve a discretionary evaluative judgment on a variety of factors about which, and within limits, reasonable minds may differ… It does not follow that simply because a judgment is published it is more authoritative than others that are not.

…

[I]t must be recognised that most of these judgments are very specifically directed to the facts and circumstances of the case at hand. It is useful for “bail authorities” to have examples of how particular factual circumstances have been considered by Supreme Court judges. But every bail application presents its own unique factual matrix.

With those observations in mind, the discussion of different factors relevant to the question of bail in individual cases in this Trends is intended to provide examples of the factors, and combination of factors, that may influence a particular decision, not to provide a definitive predictor of the outcome.

Finally, as part of the discussion of the offence of fail to appear, in s 79 of the Act, the Trends includes an analysis of the sentences imposed for such offences in the NSW Local and Children’s Courts.

The Bail Act 2013 — a history

Enactment of the Bail Act 2013

The Bail Act 2013 commenced on 20 May 2014,3 and the predecessor Bail Act 1978 was repealed.4 The new Act followed a review of NSW bail laws by the NSW Law Reform Commission (the Commission).5 The Commission noted that the 1978 Act was “one of the most convoluted and restrictive bail statutes in Australia”6 and that the “current scheme of presumptions, exceptions and exceptional circumstances [was] unduly complex and restrictive … [and] an unwarranted imposition on the discretion of police and the courts”.7

The Commission recommended that any reform retain a justification model, that is, that a person is entitled to be released unless detention is justified having regard to certain considerations.8 However, in enacting the 2013 Act, the government adopted a risk-management approach to bail decision-making.9

The key feature of the Bail Act 2013 as enacted was the unacceptable risk test which was intended to avoid the complexity of offence-based presumptions under the predecessor legislation.10 As enacted, the test required a bail authority to consider whether there was an unacceptable risk that an accused person, if released, would fail to appear, commit a serious offence, endanger the safety of victims, individuals or the community, or interfere with witnesses or evidence.11 Bail could be refused only if the bail authority was satisfied there was an unacceptable risk which could not be sufficiently mitigated by imposing bail conditions.12

Interim report of the review of the Bail Act 2013 and the Bail Amendment Act 2014

Within weeks of the new Act being in force, the NSW Premier announced an urgent review in light of concerns that “recent bail decisions do not reflect the government’s intention to put community safety front and centre”.13 An interim report, published in July 2014, noted difficulties with the community accepting that an accused who presented an unacceptable risk could be safely released into the community even with strict bail conditions.14 The review also recommended introducing a show cause requirement for serious offences.15

The Bail Amendment Act 2014 commenced on 28 January 201516 and adopted the recommendations made in the interim report.17 In addition to the unacceptable risk test, it introduced a show cause requirement, in s 16A, requiring a bail authority making a bail decision for a show cause offence18 to refuse bail unless the accused shows cause why their detention is not justified.19 The Attorney General distinguished show cause offences from the presumptions which had existed under the 1978 Act saying “unlike presumptions, determining show cause will not be the end of the matter”.20 The Act also consolidated the unacceptable risk test from a two-stage to a one-stage test and introduced the concept of “bail concerns” in s 17. Under the reformulated test, a bail authority must assess bail concerns (that is, whether there is a concern an accused, if released from custody, will fail to appear, commit a serious offence, endanger the safety of victims, individuals or the community, or interfere with witnesses or evidence) and must refuse bail if, on an assessment of those concerns, there is an unacceptable risk: ss 17(1)–(2); 19(1).

The presumption of innocence and the general right to be at liberty were repealed from s 3, and instead inserted as part of a preamble. The preamble states that, in enacting the Act, Parliament also had regard to the need to ensure the safety of victims of crime, individuals, and the community, and the need to ensure the integrity of the justice system.21 The Attorney General said this was because “[t]he review noted that the presumption of innocence and general right to liberty are more appropriately reflected as principles in a preamble rather than as a purpose of the Act”.22 In JM v R,23 Garling J referred to the continued importance of these common law principles and the purpose of the preamble, observing “[a] court needs to keep in mind, and have regard to these principles when considering a grant of bail, because as a fundament of the law, they have not been excluded by the terms of the Act. On the contrary, the Parliament has embraced them”.

Bail Amendment Act 2015

The Bail Amendment Act 2015 commenced on 5 November 201524 and introduced further amendments to the Act based on subsequent reviews and recommendations.25 An additional offence category was added to the show cause requirement,26 and additional matters were added to the list of considerations in the assessment of bail concerns. These included, for example, the accused’s history of compliance or non-compliance with various orders; the likelihood of a custodial sentence being imposed for the offence; whether the accused has any associations with a terrorist organisation or person or group advocating support for a terrorist organisation, or has made statements or carried out activities advocating support for terrorist acts or violent extremism.27 A new provision, s 22A, was introduced to provide that a bail authority must refuse bail for terrorism related offences unless exceptional circumstances are established.28

Jurisdiction and procedure

Types of application

There are three types of bail application:

a release application may be made by a person accused of an offence, for bail to be granted or dispensed with: s 49.

a detention application may be made by the prosecutor in proceedings for an offence for the refusal or revocation of bail for an offence, or for the grant of bail with the imposition of bail conditions: s 50.

a variation application may be made by any interested person: s 51.29

General court powers relating to bail

Parts 3, 5 and 6 of the Act contain various provisions relevant to a court’s jurisdiction to exercise the power to hear, make or vary bail decisions.

An accused has a right to release for certain offences and, in such circumstances, the court must release the person without bail, dispense with bail or, grant bail with or without conditions: s 21. Offences for which there is a right to release include fine-only offences, offences under the Summary Offences Act 1988 (other than “excluded offences” which are defined in s 21(3))30 and offences dealt with by conference under Pt 5 of the Young Offenders Act 1997. An offence is not one for which there is a right to release if the accused has previously failed to comply with a bail acknowledgement or a bail condition for an offence: s 21(4). A court may make, or vary, a bail decision following the making of one of the bail applications summarised above, after hearing a bail application: s 48(1). A particular court only has the power to hear an application in the circumstances specified in Pt 6 of the Act, summarised in Table 1 below.

In general terms, a court has power to hear a bail application if:

proceedings for the offence are pending in the court: s 61, or

proceedings on an appeal against conviction or sentence are pending in another court in which the accused has not yet made a first appearance: s 62, or

the application is to vary a bail decision made by the court: s 63(1).

Additional powers, set out in Pt 5, Div 3 include, when an accused first appears, a discretion for a court, of its own motion, to grant or vary bail where to do so would benefit the accused: s 53(1). A limitation on that power is that it does not apply to show cause offences: s 53(4).

Jurisdiction of particular courts

Part 6, Div 3 of the Act sets out the powers specific to each court. These powers are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Specific powers of particular courts under the Bail Act 2013

| Court | Powers under the Bail Act 2013 |

|---|---|

| Local Court31 |

|

| District Court33 |

|

| Supreme Court |

|

| Court of Criminal Appeal |

|

The scope of the Court of Criminal Appeal’s powers to grant bail in certain of the situations identified in s 67 of the Act is not free from doubt. For example, in Karout v DPP (NSW),36 an application for bail was made in circumstances where the applicant had applied for, but not been granted, special leave to appeal to the High Court following an unsuccessful sentence appeal in the Court of Criminal Appeal. The court concluded it did not have jurisdiction to grant bail under s 67(1)(d) as there was no appeal “pending” in the High Court and that if the legislature intended s 67(1)(d) to extend to an application for special leave then words to that effect would appear in the Act. As to whether the court could stay the sentence and then grant bail under s 67(1)(c), which enables the court to hear a bail application if a stay of execution of a conviction is in force, the court was reluctant to express a concluded view observing “it is an open question as to whether the applicant can rely upon s 67(1)(c)”.37

Manner of applications

The Bail Regulation 2014 sets out requirements as to the manner and form in which particular applications may be made.

A release application may be made by an accused person orally, if they are before the court, or in writing: cl 16(1). A prosecutor must make a detention application in writing and in the approved form, where practicable: cl 17(1). However, a court or authorised justice cannot decline to hear a detention application solely because it is not made in writing: cl 17(1A)(2). Variation applications are generally to be made in writing and in the approved form, although an accused may make a variation application orally if they are before the court: cll 20(1)–(2). A court may make a decision on a variation application even if it does not comply with the approved application format: cl 20(3).

To assist the court in its assessment of bail concerns, which is central to determining whether or not there is an unacceptable risk, both the prosecution and the defence present evidence (accepting the rules of evidence do not apply) to assist in that assessment. In every application, the prosecution would tender the statement of facts, the accused’s criminal history and bail history (where either or both exist) and other material related to the issue of whether there is an unacceptable risk such that bail must be refused. “Other material” might extend to information about property an accused may own, or have an interest in, overseas; passports in false names; access to unexplained funds; or, in some drug cases, information about an accused’s associations with other alleged drug syndicates. For applications in the Supreme Court, practitioners must have regard to the relevant Practice Note which outlines the practice and procedure to be adopted for preparing and filing an application in that court.38

The prosecution should be discriminating about addressing only those bail concerns that apply in an individual case. In Kane v DPP39 the court observed that “[a]s is becoming an almost standard approach, the Crown has nominated each of the bail concerns listed in ss 17(2)(a)–(d) of the Bail Act as being unacceptable risks” but had then agreed before the court that the bail concerns nominated could be adequately addressed by conditions. In Decision Restricted [2016] NSWSC 21540 Harrison J said:

… the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions appears these days almost always or without exception to oppose bail in every case with no obvious attempt to differentiate or discriminate among them … So mechanical and predictable have these expressions of bail concerns become that they potentially but significantly diminish the degree of reliance that can be placed upon submissions said to support them without considerable further examination. This approach also raises the distasteful spectre of the existence of some kind of internal directive that bail is to be opposed as a matter of principle in every case regardless of the merits of the particular applicant concerned.

The accused will generally rally material to demonstrate that the level of risk can be minimised. For example, offering security, ensuring reliable accommodation has been arranged and demonstrating a commitment to rehabilitation. More must be done than simply making a submission about these matters — care must be taken that sufficient material is presented to the court to enable it to make the relevant decision. In addition, the accused may also highlight deficiencies in the Crown case, point to procedural issues which may delay any hearing and raise issues of hardship or other subjective matters in favour of their release.

Requirements for reasonable notice

A court must not hear a detention or variation application made by a person other than the accused unless satisfied reasonable notice has been given to the accused: ss 50(5), 51(6). Reasonable notice must also be given to a prosecutor when a variation application is made by a party other than the prosecutor: s 51(7). The court may dispense with notice if satisfied the accused is evading service or cannot be contacted, or that the interests of justice so demand: Bail Regulation 2014, cl 18(4).

Whether notice is reasonable will reflect a variety of circumstances depending on the particular case.41 The question is not whether the accused has been given reasonable notice of the application, but whether the court or authorised justice is satisfied that such notice has been given.42 The assessment as to what is “reasonable notice” in any individual case must have regard to the requirement under s 71 that bail applications be dealt with as soon as reasonably practicable.43 The court in Barr (a pseudonym) v DPP (NSW)44 observed that a judge’s determination as to whether reasonable notice had been given under s 50(5) was capable of scrutiny on an application for judicial review (although the majority found it unnecessary to determine).45

General procedural and evidential matters

The requirement in s 71 that a bail application be dealt with as soon as reasonably practicable imports a sense of urgency, however it is only as urgent as the limited resources of a court will permit.46 In Ahmad v DPP,47 where a bail application was adjourned to a date after the date fixed for committal, Campbell J found the matter was not dealt with in accordance with the duty imposed by s 71.

A court must hear any release or variation application made by an accused on a first appearance in substantive proceedings for an offence: s 72(1).

Bail matters are to be decided on the balance of probabilities: s 32(1). The rules of evidence do not apply but a bail authority may take into account any evidence or information it considers credible or trustworthy in the circumstances: s 31(1). Whether that relatively low threshold is met can be determined when the information is provided, or when the bail application is determined.48 A bail authority can therefore avoid making “rulings” on whether or not material with apparent relevance should be received, and can instead receive the material and give it “such weight as it considers appropriate in its deliberations”.49

However, the fact the court is not bound by the rules of evidence does not mean it is obliged to ignore the policy and rationale underlying them.50 This may include scepticism of conclusions which are unsupported by any factual detail. In DPP (NSW) v Mawad,51 for example, a police officer’s opinion about the respondent’s ability to access weapons and his alleged “criminal connections” was given no weight because of the absence of any detail setting out the basis for the assertions.

Any bail application is to be dealt with as a new hearing, and evidence or information may be given in addition to, or in substitution for, any evidence or information given in relation to an earlier bail decision: s 75. There is no need for the court hearing any subsequent application to be persuaded of any error.52 The form of “new hearing” is to be approached with a degree of flexibility, depending upon the circumstances of the particular case.53 Where oral evidence has been called at an earlier hearing, the court should be entitled to take account of reasons and findings made in the earlier proceeding, including findings about the credibility of witnesses.54

Multiple applications

Second or subsequent release applications (after a refusal of bail) or detention applications (after a grant of bail) are not permitted in the same court unless there are grounds for a further application: ss 74(1)–(2). Section 74 is a conditional prohibition on hearing further applications of the same type, that is, the provision says nothing about constraints on the court hearing a release application after it has granted a detention application (and vice versa).55

The available grounds for further applications are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2. Grounds for further release or detention application

| Grounds | Further release applications: s 74(3) | Further detention application: s 74(4) |

|---|---|---|

| The person was not legally represented at the time of the prior application and now has legal representation | ✔ | ✘ |

| Material information relevant to the grant of bail, which was not presented in the initial application, is to be presented56 | ✔ | ✔ |

| Circumstances relevant to the grant of bail have changed | ✔ | ✔ |

| The person is a child and the previous application was made in a first appearance for an offence | ✔ | ✘ |

Additional information will be material if the applicant satisfies the court that the previous application may have had a different outcome had the additional information been presented.57 A change in surety and the amount offered has been held to constitute “material information” not presented before, although it is always a matter of fact and degree and must be assessed in the context of the seriousness of the charge and all other relevant circumstances.58

It has been found the result of plea negotiations could amount to a change in relevant circumstances.59 However, where negotiations have merely commenced, which may or may not result in any agreement, this does not satisfy the requirement.60 A delay finalising a trial which goes beyond that envisaged at the time of a first application may constitute a change in relevant circumstances.61 A change of circumstances was also established in Tsintzas v DPP (NSW),62 where the accused’s two sons were seriously injured in a motor vehicle accident, and in R v Boatswain,63 where the accused’s terminal liver cancer had progressed to a point where his life expectancy was limited to hours or days.

Requirement for reasons

Section 38(1) of the Act requires a bail authority that refuses bail to immediately record the reasons for refusing bail, including (if refused because of an unacceptable risk) the unacceptable risk(s) identified. Where bail conditions are imposed, the bail authority must immediately make a record of the reasons why bail was not granted unconditionally, and set out the bail concern(s) identified: s 38(2). This must include reasons for imposing any security requirement or requiring character acknowledgments: s 38(3). Reasons must also be provided for the imposition of conditions other than those requested by an accused: s 38(4).

Process for determining release and detention applications

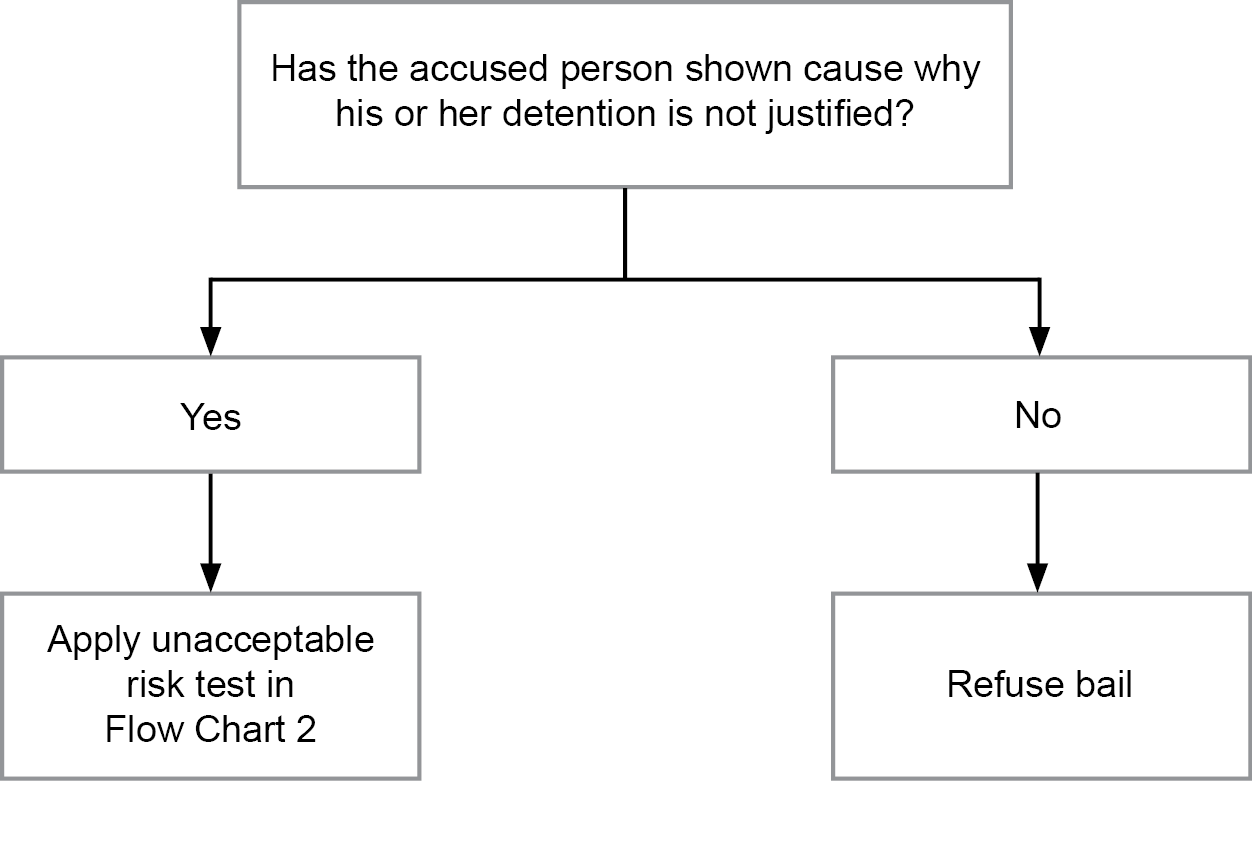

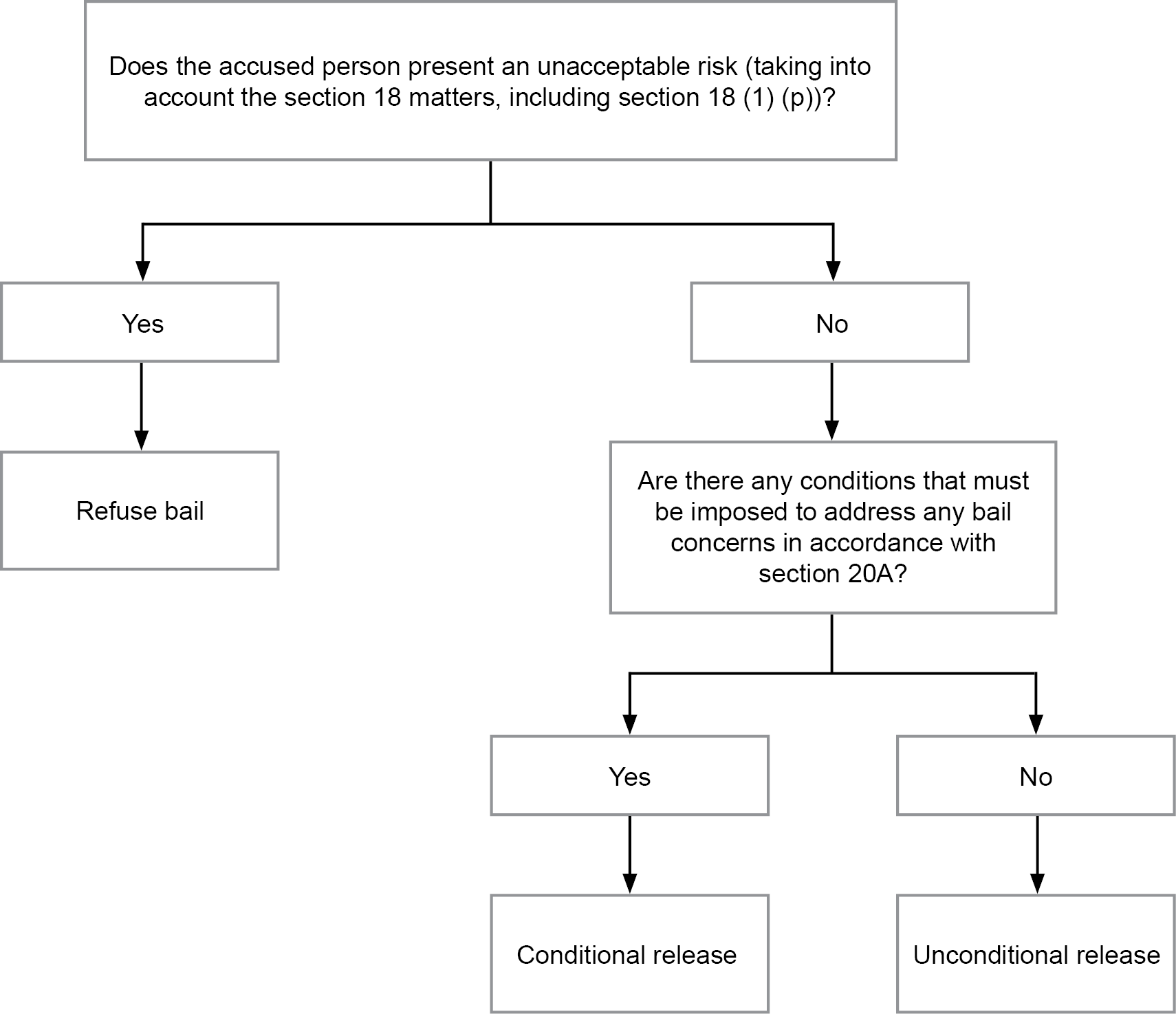

Section 16 of the Act contains two flow charts which set out the bail decision process. Flow Chart 1 illustrates the show cause requirement (Div 1A) which applies only to show cause offences and Flow Chart 2 illustrates the unacceptable risk test (Div 2) as it applies to all offences, other than offences for which there is a right to release: ss 16(1)–(3), 21.64

A bail authority making a bail decision for a show cause offence must refuse bail unless the accused shows cause why their detention is not justified: s 16A(1).

The terms of s 16A(2) make clear there is a two-step process when determining release and detention applications for show cause offences.65 If a person charged with an offence of a type listed in s 16B shows cause why their detention is not justified, the bail authority must then separately consider whether there is an “unacceptable risk” in accordance with s 19. The unacceptable risk test applies to all offences including those for which there is a right to release: s 21(5).66 Both assessments need to be made by reference to any evidence or information the bail authority considers credible or trustworthy in the circumstances and on the balance of probabilities: ss 31, 32. Whether a person has shown cause, and whether there are unacceptable risks, are evaluative decisions requiring the identification of all factors relevant to the particular application and an assessment of the weight to be attached to each of those factors.67 In JM v R68 Garling J said:

Both tests … involve, although to a lesser degree for the show cause test, an exercise of the prediction of human behaviour, to which no certainty can ever be attached. Reasonable minds may well differ on the result of a bail application.69

It is important not to conflate the show cause requirement and the unacceptable risk test.70 Parliament has not enumerated the factors that may show cause, in contrast to the exhaustive list of factors set out in s 18 that are relevant to the assessment of unacceptable risks.71 Consequently, there are matters relevant to the show cause requirement not available to be considered in relation to the unacceptable risk test. For example, a jury’s verdict of guilty is not within the matters listed in s 18 yet is relevant to the question whether an applicant’s continuing detention is justified while they await sentence, since the presumption of innocence has been rebutted by that verdict.72 On the other hand, in many instances the same factors will inform both tests, including for example, the strength of the Crown case, criminal antecedents and delay.73 Further, the Act does not prohibit, in determining the show cause requirement, a consideration of any bail concerns.74

However, while one factor may be relevant to both tests, that factor may not be relevant to the same issue at the two separate stages of the process. In Barr (a pseudonym) v DPP (NSW)75 N Adams J said:

… a weak Crown case might be relevant to the show cause test as it might not be justified to detain a person for a lengthy period of time if they may not be convicted. That same factor may again be relevant to the question of the risk of flight: a person facing a strong Crown case would, as a general rule, be a greater flight risk than a person facing a weak case.

Show cause requirement — Pt 3, Div 1A

Where the offence is a “show cause” offence, s 16A(1) provides that the onus is on the accused to show cause why their detention is not justified.76 Show cause offences are listed in s 16B and include:

offences punishable by life imprisonment: s 16B(1)(a)

certain serious indictable child sexual assault offences: s 16B(1)(b)

a serious personal violence offence or an offence involving wounding or the infliction of grievous bodily harm, if the accused has previously been convicted of a serious personal violence offence: s 16B(1)(c)

a serious indictable offence under Pt 3 (offences against the person) or 3A (offences relating to public order) of the Crimes Act 1900, certain firearms and weapons offences under the Firearms Act 1996 or the Weapons Prohibition Act 1998 and indictable offences involving unlawful possession of a pistol or firearm (in a public place) or a military style weapon: ss 16B(1)(d) and (e)

offences involving the cultivation, supply, possession, manufacture or production of a commercial quantity of a prohibited drug or prohibited plant contrary to the Drug Misuse and Trafficking Act 1985: s 16B(1)(f), or offences involving the possession, trafficking, cultivation, sale, manufacture, importation, exportation or supply of a commercial quantity of a serious drug contrary to Pt 9.1 of the Commonwealth Criminal Code: s 16B(1)(g)

a serious indictable offence committed while the person was on bail or parole, or an indictable offence (or offence of failing to comply with a supervision order) committed while subject to a supervision order: ss 16B(1)(h) and (i)

attempting to commit a serious indictable offence mentioned in s 16B or a serious indictable offence of assisting, aiding, abetting, counselling, procuring, soliciting, being an accessory to, encouraging, inciting or conspiring to commit an offence mentioned in s 16B: ss 16B(1)(j) and (k)

a serious indictable offence committed while the person is subject to an arrest warrant: s 16B(1)(l).

Section 16A does not apply to persons under 18 years old at the time of the alleged offence(s): s 16A(3).

The Act does not contain an exhaustive list or inclusive definition of what an accused needs to establish in order to show cause under s 16A.77 The test requires the accused to point to factors that, either alone or in combination, support a conclusion that their continued detention is not justified.78 Ultimately, whether cause has been shown is determined by considering all the evidence, not just those matters in s 18 which are required to be considered for the unacceptable risk test.79 Cause may be demonstrated by a single powerful factor, or a powerful combination of factors.80 For example, in DPP (NSW) v Brooks,81 the court held that there was nothing special or unusual in respect of the respondent’s age, lack of criminal antecedents, ties to the community and strong family support and that cause had not been shown. Subsequently in DPP (NSW) v Mawad,82 the court clarified that this did not mean these factors could never amount to showing cause but merely that they did not amount to showing cause in the circumstances of that particular case: each must turn on its own circumstances. It may also be shown by a combination of personal circumstances and broader interests of expeditious justice.83

No onus or gloss should be put on the words in s 16A; for example, it is not incumbent upon an accused to demonstrate special or exceptional circumstances in order to show cause.84 In R v Tsallas85 Harrison J observed:

It is regrettable that the Parliament did not see its way clear to offering some guidance as to the matters that should be taken into account in assessing the show cause requirement, or better still to circumscribing a test such as a special or exceptional circumstances test, or an inclusive test specifying factors that an applicant would have to satisfy or demonstrate applied in his or her case, in order to show cause as required.

However, while the inclusion of s 16A does not mean the legislature has declared an intention that bail will not ordinarily or normally be granted for show cause offences,86 in R v Xi, Hamill J observed “the cases that have been decided by appellate courts show that the show cause requirement establishes a significant hurdle to an applicant seeking bail when s 16A is engaged”.87

The requirement remains the same regardless of whether or not a previous application has been granted in the case. For example, where a detention application is heard by the Court of Criminal Appeal following a grant of bail by a single judge of the Supreme Court, there is no requirement for the Court of Criminal Appeal to exercise restraint when determining whether the accused has shown cause. The detention application must be determined on a de novo basis by reference to the Bail Act provisions which do not suggest any form of restraint.88

Specific factors relevant to the show cause requirement

Strength of the Crown case

The strength of the Crown case has a direct bearing on whether an accused has shown cause why their detention is not justified.89 In R v Fallon (a pseudonym), Campbell J said:90

Typically, the circumstances propounded for the purpose of showing cause and other relevant matters are viewed through the prism of the strength of the Crown case.

However, an assessment that the Crown case is strong is not determinative and does not carry the same weight it did under the repealed 1978 Act.91 A weak Crown case may be relevant to show that detention for a lengthy period of time is not justified on the basis the accused may not be convicted92 and has, on its own, satisfied the show cause requirement.93

Further, the assessment of the strength of the Crown case is an impressionistic one,94 limited by both the material available to the bail court and the fact it is usually quite distant from the final hearing. The assessment is made in what are essentially summary and truncated proceedings in a busy court list. Ultimately, prosecution witnesses may not give evidence at trial, and if they do, they may not give evidence in accordance with their statements; a different picture may emerge during cross-examination; and a jury, judge or magistrate, may take an adverse view of the demeanour or credibility of a witness during the trial, not contemplated at the bail stage.95 Importantly, it should be borne in mind that it is not the role of the bail court to predict, much less definitively determine, how the various issues arising from witnesses and reliability of evidence will be resolved.96

In Moukhallaletti v DPP (NSW),97 for example, the accused did not show cause why his detention was not justified in circumstances where there was a strong Crown case, in combination with the fact imprisonment was likely if he were convicted and there was a risk he may fail to appear at proceedings.

Delay in proceedings and length of time to be spent in custody

The length of time spent, and/or to be spent in custody, bail refused is relevant to whether an accused has shown cause.98

In R v Cain (No 1),99 a case involving serious drug importation charges, Sperling J said:

the prospect that a private citizen who has not been convicted of any offence might be imprisoned for as long as two years pending trial is, absent exceptional circumstances, not consistent with modern concepts of civil rights.

R v Cain (No 1) was decided under the 1978 Act but delay remains a relevant consideration with respect to the show cause requirement and the case’s continued relevance was referred to by McCallum J in R v Farrell,100 who added:

The Court must be astute to ensure that those concepts are not eroded by progressive numbness to delay or its normalisation due to the jading impact of straining against the stretched resources of the criminal justice system.

…

The simple fact is that three years is too long a period, absent unacceptable risk, for a person who has not been convicted of any offence to be imprisoned awaiting trial.

Delay in proceedings pending trial or sentence will be significant even where there is a strong Crown case.101 However, significant delay is usually not, of itself, sufficient to show cause.102 The delay must be assessed in the circumstances of the particular case, not against other cases, and must be considered not simply as a bland number of years, but against the history of the proceedings.103

For example, in DPP (NSW) v Boatswain,104 delay was found to carry greater weight in circumstances where the accused was suffering from a terminal illness and had a short life expectancy. In DPP (NSW) v Zaiter,105 the delay (almost 2 years between bail being refused and the trial) was largely a result of the time taken for the prosecution to compile and serve its brief of evidence but also because of the accused changing his legal representation. The prospective delay between committal and trial was unremarkable given the heavy caseload then pending in the District Court, but was still concerning and an important factor in determining show cause.

In Fantakis v R; Woods v R106 the two accused did not show cause why their detention was unjustified despite an expected 4 years, 4 months on remand awaiting trial. Justice Wilson observed that had the delay been entirely attributable to the Crown, or to the court’s inability to offer a timely trial date, the delay would have been of more persuasive significance.

In DPP (NSW) v Hing,107 a case where the accused was likely to serve 12 months in custody prior to his trial for money laundering offences, the court said:

Such a delay is, of course, regrettable. However with the current work load of the District Court it cannot be said to be out of the ordinary. In fact, it is not out of the ordinary for serious criminal charges in both the District Court and the Supreme Court to take up to 18 months or 2 years from arrest until finalisation.

…

[T]he prospective delay in this matter is most concerning. However it is a matter that was required to be balanced against all of the other circumstances of the case.

In R v AC (No 3) (Detention application),108 the accused demonstrated cause primarily on the basis the refusal of bail would delay his co-offender’s trial. Justice Hamill noted that delay in a joint trial not only affects the accused but the victims and witnesses who have an interest in justice being done expeditiously. His Honour said that while the delay was not determinative, it was one of the many factors leading him to conclude that the combination of circumstances in that case were so unusual that despite the inevitability of a long gaol sentence, the accused should remain on bail.

Whether a sentence of imprisonment is likely

The inevitability that the accused will be sentenced to a significant term of imprisonment if convicted may also be relevant when determining whether the accused has shown cause.109 However, a bail application should not be approached on the basis that it would be sensible or expedient for the accused to begin serving an apparently inevitable custodial sentence now rather than at a later point when he or she is duly sentenced.110

Where it is uncertain a custodial sentence will be imposed for the offence or pre-sentence custody is likely to exceed the custodial sentence ultimately imposed, this will also be relevant to the show cause assessment.111 For example, in R v McCormack,112 the court found the accused, who was charged with various firearm offences, had shown cause in circumstances where it was by no means certain he would be sentenced to full time custody, the prosecution had decided not to proceed with the charges on indictment but in the Local Court, he had spent 2 months in custody bail refused, was 65 years of age with health issues, and had no prior history of violent offending.

Family vulnerability or needs

In some circumstances, family vulnerability or hardship may be sufficient.113 This has included where the accused has children with severe disabilities in need of special care.114 In Mawad115 the Supreme Court and Court of Criminal Appeal found the accused had shown cause, despite the strong and serious Crown case, on the basis of compelling evidence of the particular vulnerability of his family in his absence. His children had severe disabilities including a hearing impairment and autism spectrum disorder.116 Similarly, cause was shown in Tsintzas v DPP (NSW)117 on the basis of the accused’s need to care for his two sons who had been seriously injured in a motor vehicle accident. However, the court noted:

There is no authority for the proposition that any form of hardship to a family will necessarily establish that cause is shown. Rather, the court makes an evaluative judgment in each case. [Emphasis added.]

Preparing a defence

The need for an accused to be free to prepare for their appearance in court or to obtain legal advice are relevant factors in showing cause.118 In Katelaris v DPP (NSW),119 the difficulty of preparing the complex legal defence of “medical necessity” while in custody, in circumstances where there was a possibility the accused would be representing himself and had difficulties accessing legal resources and expert evidence, combined with other factors, satisfied the show cause requirement. Limited English, combined with a lack of suitable translators resulting in difficulties communicating with legal representatives while in custody, has also been a significant factor relevant to the show cause requirement.120 Similarly, dyslexia and poor literacy skills have been held to be relevant matters in showing cause on the basis preparation for the trial will be more difficult.121

The need to be free to prepare a defence requires the court to give careful consideration to how much material needs to be reviewed by the accused themselves.122 It will be an unusual case where an accused is able to show cause because of the difficulties in preparing their defence as a result of their incarceration.123 In DPP (Cth) v Heng,124 the court was satisfied the respondent’s computer access in custody would meet his requirements and he had not shown that his continued detention was unjustified on grounds of exigencies of defence preparation or otherwise. Similarly, in Decision Restricted [2018] NSWSC 996 125 the court found the accused’s claimed need to be released to assist in de-encrypting hard drives from recording devices for his defence was not sufficient to show cause.

Health issues

Another relevant factor in determining the show cause requirement is whether the accused is suffering from a life threatening or significant medical condition that could not adequately be managed in or from a correctional facility or would make custody more onerous.126 Impending death from disease or injury may also satisfy the show cause requirement.127 In DPP (NSW) v Boatswain,128 a murder case, the respondent’s terminal liver cancer and relatively short life expectancy significantly contributed to him being able to show cause (although bail was refused because he posed an unacceptable risk of committing another offence and interfering with witnesses).

The opportunity to enter rehabilitation

The opportunity to enter residential rehabilitation, particularly where an accused demonstrates a considerable commitment to rehabilitation and obtaining a bed, is also a relevant factor.129 Some courts have observed that where there is a short period of time between the bail application and the sentence date, allowing a person bail to enter a residential rehabilitation program could be perceived as the bail court fettering the sentencing judge’s discretion.130 However, there are divergent views on this issue.131

“Bugmy” factors

A lengthy period on remand and separation from a child in the context of disadvantage and deprivation within an Indigenous community (in the circumstances described by the High Court in Bugmy v The Queen),132 has been considered a significant factor in showing cause. In R v Alchin,133 McCallum J said:

During [the period on remand] the applicant would in all likelihood see very little of the child if refused bail. That is a factor which seems to me to be likely to perpetuate the cycle of disadvantage and deprivation notoriously faced in indigenous communities … If the Court can reasonably impose conditions which are calculated to break that cycle, in my view it should. That is a strong factor in my finding cause shown.

Other factors

Once an accused enters a guilty plea or a verdict of guilty is returned, the presumption of innocence ceases to be a consideration. However, the fact of the plea or the verdict itself may still be considered when determining whether an offender has shown cause. In R v Tasker (No 2),134 Button J indicated an intention to grant bail for a show cause offence, however upon subsequently becoming aware the accused had pleaded guilty, refused bail. The guilty plea meant the accused was no longer entitled to the presumption of innocence, any weaknesses in the Crown case were irrelevant, there was no chance the accused would be convicted of the less serious alternative offence; and a substantial period of imprisonment was inevitable. Similarly, in DPP (NSW) v Tikomaimaleya135 the applicant’s conviction was a central consideration persuading the court that cause had not been shown. The court said:

The jury’s verdict of guilty is not within any of the matters listed in s 18; yet it is plainly germane to the question whether cause can be shown that his continuing detention is unjustified, since the presumption of innocence, which operated in his favour before the jury returned its verdict, has been rebutted by that verdict.

Other factors which may be relevant to the show cause requirement include:

the strength of the bail proposal136

the accused’s criminal record or an absence of prior offending137

the risk the accused may fail to appear at proceedings140

being young and in custody for the first time141

the need for protective custody coupled with a lengthy period on remand142

threats of assault of established violence that could not be adequately ameliorated by Corrective Services143

relatively minor offences144

the potential to access financial resources145 and large quantities of drugs146

a large surety147

the fact an accused will be held on remand in a different State to their family.148

Unacceptable risk test — Pt 3, Div 2

The provisions governing the unacceptable risk test, which applies to all offences, are in Pt 3, Div 2 of the Act. Before applying the unacceptable risk test, the bail authority must assess any bail concerns: s 17(1).149 Section 17(2) provides that a “bail concern” is a concern that the accused, if released from custody, will:

- (a)

fail to appear at any proceedings for the offence, or

- (b)

commit a serious offence, or

- (c)

endanger the safety of victims, individuals or the community, or

- (d)

interfere with witnesses or evidence.

While a “serious offence” in s 17(2)(b) is not defined, s 18(2) gives some guidance by identifying the following as matters to be considered:

- (a)

whether the offence is of a sexual or violent nature or involves possession or use of an offensive weapon or instrument within the meaning of the Crimes Act 1900

- (b)

the likely effect of the offence on any victim and on the community generally

- (c)

the number of offences likely to be committed or for which the person has been granted bail or released on parole.

This list is not exhaustive and the court must determine, on a case by case basis, what amounts to a “serious offence”.150 For example, in DPP (NSW) v Dagdanasar,151 a case where the accused had been charged with two driving whilst disqualified offences and had a significant driving record, RA Hulme J found that any further offence of driving whilst disqualified should be considered “a serious offence”.

The type of bail decision that may be made following an assessment of whether or not there is an unacceptable risk depends on the offence. If the offence is one in respect of which there is a right to release, then the court can only release the accused without bail, dispense with bail, or impose bail with or without conditions: s 21(1). However, for other offences, bail must be refused if the bail authority is satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that there is an unacceptable risk: ss 19(1)–(2), 32(1). If the offence is a show cause offence, the fact an accused has shown cause why their detention is not justified is not relevant to the determination of whether or not there is an unacceptable risk: s 19(3). If there are no unacceptable risks, the bail authority must grant bail (with or without imposing conditions), release the person without bail, or dispense with bail: s 20(1).

The concept of “unacceptable risk” under s 19

The term “unacceptable risk” is defined in s 4(1) by reference to s 19.

The meaning of the phrase “unacceptable risk” should be determined by reading the statute as a whole having regard to the context of s 19 and the objects of the Act.152 Consideration in this way gives practical content to the meaning of the phrase.153 The importance of the context in which the phrase “unacceptable risk” is used in particular legislation was considered by the Court of Appeal in Lynn v State of NSW154 which concerned s 5E(3) of the Crimes (High Risk Offenders) Act 2006. In that case, the court cautioned against using interstate authorities and cases concerning other NSW statutory provisions to interpret the expression and found that the phrase as used in the Bail Act did not assist in construing it for the purposes of the high risk offender legislation. However, Beazley P (with whom Gleeson JA agreed) considered that it was apparent the assessment of an “unacceptable risk” in the context of a bail authority determining whether to grant bail “is both context specific and prescriptive”.

The task of assessing whether there is an unacceptable risk in a particular case for the purpose of s 19 is an evaluative one which involves considering the various bail concerns identified in s 18. It is also impacted by other provisions in the Act: for example, the absence of the rules of evidence, the applicable standard of proof (s 32), and the fact the task may be undertaken by reference to evidence the bail authority considers credible or trustworthy (s 31).

The difficulty of estimating risk has been recognised, but in R v SK; R v DK155 McCallum J observed that the Act “does not contemplate the absence of any risk if a person is released, but the informed balancing of risk”.

Matters to be considered in assessing bail concerns — s 18(1)

The matters to be considered as part of the assessment of bail concerns are exhaustively listed in s 18(1).156 These are:

the background, criminal history, circumstances and community ties of the accused: s 18(1)(a)

the nature and seriousness of the offence: s 18(1)(b)

the strength of the prosecution case: s 18(1)(c)

any history of violence by the accused: s 18(1)(d)

previous commission of a serious offence while on bail: s 18(1)(e)

history of compliance, or non-compliance with previous bail acknowledgments, bail conditions or other specified orders of the court: s 18(1)(f)

warnings issued by police officers or bail authorities regarding non-compliance with bail acknowledgments or bail conditions: s 18(1)(f1)

any criminal associations: s 18(1)(g)

length of time likely to be spent in custody if bail is refused: s 18(1)(h)

likelihood of a custodial sentence being imposed following a conviction: ss 18(1)(i) and (i1)

the reasonably arguable prospect of success if a pending appeal is before the court: s 18(1)(j)

any special vulnerability or needs due to youth, being Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, or having a cognitive or mental health impairment: s 18(1)(k)

the need to be free to prepare for court appearances or obtain legal advice or for any other reason: ss 18(1)(l) and (m)

the accused’s conduct towards any victim, or family member of the victim, after the offence: s 18(1)(n)

in the case of a serious offence, the views of any victim, or family of the victim, concerning the safety of victims, individuals or community if the accused were released from custody: s 18(1)(o)

the bail conditions that could reasonably be imposed to address any bail concerns in accordance with s 20A: s 18(1)(p)

the accused’s association with any terrorist organisation; or whether they have made any statements or carried out activities advocating support for terrorist acts or violent extremism; or whether they have any associations or affiliations with persons or groups advocating support for terrorist acts or violent extremism: ss 18(1)(q), (r) and (s).

It is recognised that there is a degree of overlap between the factors the court may consider under the show cause requirement in s 16A and the factors to be taken into account when determining unacceptable risk.157 Consequently, many of the factors to be considered under s 18 have already been discussed in the context of the show cause requirement above at p 12ff. In practice, bail courts tend to deal with issues such as delay and the strength of the Crown case once, without separately addressing them in respect of each test. Each of the matters in s 18(1) is to be given equal priority; no one matter assumes dominant significance.158 Further, the considerations in s 18 are very much matters of fact and degree upon which minds might reasonably differ159 and the material going to bail concerns will pull in different directions.160 Cases addressing some of the more common s 18(1) factors are discussed below.

Specific matters to be considered under s 18

Strength of the Crown case — s 18(1)(c)

The strength of the Crown case under s 18(1)(c) must be taken into account in assessing unacceptable risk. The limitations inherent in assessing the Crown case have been discussed above at p 14. In DPP (NSW) v Mawad161 the court said in respect of assessing the Crown case under s 18(1):

Bail applications are not suitable forums to conduct mini trials. Nevertheless, an assessment of the strength of the Crown case is important to an assessment of prospective risk which is at the heart of the process of determining whether or not to grant bail.

Delay — s 18(1)(h)

Section 18(1)(h) identifies the “length of time the accused person is likely to spend in custody if bail is refused” as one of the matters to be considered when assessing bail concerns. This interacts with other factors in s 18 including ss 18(1)(i) and (l) which refer respectively to the likelihood of a custodial sentence being imposed and the need for an accused person to be free to prepare for their appearance in court or to obtain legal advice. In DPP (NSW) v Mawad162 Beech-Jones J (Gleeson JA agreeing) said:

[s 18(1(h)] informs the unacceptable risk test in s 19(1) in that a consideration of what level of risk is “unacceptable” can involve a consideration of the undesirability of persons spending prolonged periods in pre-trial custody. Such an outcome is inimical to a system of justice that has as its foundation the presumption of innocence.

These observations were also reflected in R v Kugor,163 a case where the respondent was likely to serve 15½ months in custody before his trial, where the court said:

It is a very serious matter to deprive a citizen of liberty for such a long period of time when he has not been convicted of any offence.

The expression “the length of time the accused person is likely to spend in custody if bail is refused” in s 18(1)(h) has been construed to mean the entire period the accused is in custody (for example, since arrest), not from the date of the proceedings where bail was refused.164

Likelihood of custodial sentence if the accused convicted — s 18(1)(i)

While the likelihood of a custodial sentence if the accused is convicted is a matter to be considered under s 18, an inevitable custodial sentence will not be determinative.165 Justice Garling explained the effect of s 18(1)(i) in A1 v R; A2 v R:166

[T]he court is entitled to have regard to the likelihood of a custodial sentence being imposed if an accused person is convicted of the offence. However, that factor is only to be taken into account in considering the existence of a bail concern, being one of the four matters [in s 17(2)]. Unsurprisingly, an applicant facing a lengthy jail sentence may be, depending on their personal circumstances, at greater risk of failing to appear at future proceedings.

Special vulnerability — s 18(1)(k)

Any special vulnerability or needs of the accused, including because of youth, being an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, or having a cognitive or mental health impairment should, where relevant, be taken into account in assessing bail concerns under s 18.

The sentencing principles concerning the approach taken to disadvantaged Indigenous persons, as outlined in Bugmy v The Queen,167 have been applied in bail cases.168 In R v Brown,169 the court said:

In the cases of Aboriginal accused, particularly where the applicant for bail is young, alternative culturally appropriate supervision, where appropriate, (with an emphasis on cultural awareness and overcoming the renowned anti-social effects of discrimination and/or an abused or disempowered upbringing), should be explored as a preferred option to a remand in gaol.

Similarly, in R v DS,170 Hamill J observed that:

…whilst the High Court in Bugmy v The Queen [2013] HCA 37 and Munda v Western Australia [2013] HCA 38 made it clear in a somewhat different context there should be no special rules applying to Aboriginal offenders … it is a notorious fact, if not a national shame and embarrassment, that Aboriginal people are grossly overrepresented in the gaols of New South Wales and Australia … Nevertheless those matters must take a secondary place to the proper application of the provisions of the Bail Act and the risks identified by the prosecution in the present case.

In that case, the 16-year-old Aboriginal accused was granted bail on strict conditions, in circumstances where his case worker was an extremely positive influence in his life. However, in AB v DPP (Cth)171 (a terrorism case involving a 17-year-old accused), Beech-Jones J found that despite the fact the accused was likely to remain in custody for a substantial period of time which would cause great hardship because of his young age, mental fragility, intellectual disability, and closeness to his family, he posed an unacceptable risk of committing a serious offence and endangering the safety of the community and bail was refused.

Illiteracy has also been held to amount to “special vulnerability” for the purposes of s 18(1)(k), on the basis it makes preparation of the defence case from custody more difficult.172

Preparing the defence — s 18(1)(l)

The need for the accused to be free to prepare for their appearance in court or to obtain legal advice is to be taken into account under s 18(1)(l).

In Trinh v R,173 Davies J (McCallum J agreeing) said:

Although s 18(1)(l) lists the need for the accused person to be free to prepare for his or her appearance in court or to obtain legal advice, it is not immediately apparent how that assists in the assessment of the bail concerns in s 17. I accept, however, that it is likely … that s 18 is directing the Court to undertake an evaluative weighing exercise of competing concerns, some of which are concerns of the person seeking bail that they be able to prepare their defence adequately and, for that matter, not be detained without conviction for a lengthy period of time.

In the light of the evidence that the applicant is to be included in the initial rollout of laptops I do not consider that his need to be free to prepare for his trial is a matter of great weight. It is significant in that regard that in Shalala the applicant was appearing for himself and preparing his own defence without the assistance of lawyers.

The equivalent to this subsection in the 1978 Act (repealed) was considered in Shalala v R174 where RS Hulme J said that in the normal course he would unhesitatingly have refused the accused’s application for bail. However, given the accused, who was unrepresented, was effectively prevented from preparing his case while in custody because of scant provision of any library facilities, his Honour felt constrained to grant bail. See also the discussion at p 12ff with respect to the show cause requirement.

Views of the victim — s 18(1)(o)

Where the offence is a serious offence,175 the views of the victim or any family member of the victim are a mandatory consideration under s 18(1)(o). In M v R,176 McCallum J said it was plain from the Second Reading Speech for the Bail Amendment Bill 2014177 that Parliament contemplated those views be in the form of a police statement. However her Honour noted that the court should take a careful approach and should not accept in an unqualified way any statement made by police about risk to the victim.

Bail conditions — s 18(1)(p)

Section 18(1)(p) provides that, when assessing bail concerns, the bail authority must consider the bail conditions that could reasonably be imposed to address any bail concerns in accordance with s 20A. Section 20A is discussed below.

Bail conditions

Bail conditions are to be imposed only if the bail authority is satisfied there are bail concerns: s 20A(1). A bail authority may only impose a bail condition if satisfied that:

the condition is reasonably necessary and appropriate to address the bail concern: ss 20A(2)(a), (c), and

the condition is reasonable and proportionate to the offence for which bail is granted: s 20A(2)(b), and

the condition is no more onerous than necessary to address the bail concern: s 20A(2)(d), and

it is reasonably practicable for the accused to comply with the condition: s 20A(2)(e), and

there are reasonable grounds to believe the condition is likely to be complied with: s 20A(2)(f).

The bail conditions that can be imposed are set out in Pt 3, Div 3. However additional conditions may be imposed if they comply with s 20A.

Electronic monitoring conditions

While the Bail Act does not authorise a court to impose obligations on third parties, in some bail applications the court will make its own assessment as to the willingness and capacity of some third parties to provide supervision of persons on bail.178 In R v Ebrahimi,179 Beech-Jones J said that nothing in the Act:

precludes the court from concluding, in a particular case, that persons providing electronic monitoring systems are both honest and have the capacity to provide some degree of comfort as to the whereabouts of an applicant for bail and their compliance with bail conditions.

In R v Xi180 and Lin v DPP (Cth)181 an electronic monitoring condition was imposed to address some of the bail concerns, particularly the risk each accused would fail to appear in court. However, in R v Ebrahimi,182 Beech-Jones J found that while electronic monitoring mitigated the risk of the accused absconding, it did not eliminate it and the delay between notification of any violation and action being taken by police was such that the accused could leave the jurisdiction. Similarly in R v Salameh,183 electronic monitoring could not adequately address the bail concerns that the accused would commit further offences and/or abscond.184

Surety conditions

A bail condition can require security to be provided for compliance with a bail acknowledgment: s 26. Where a person granted bail fails to appear in accordance with their bail acknowledgment, the court has power to make an order forfeiting to the Crown any bail money associated with a bail acknowledgment.185 “Bail money” is defined in s 4 as money agreed to be forfeited under a bail security agreement. A large surety may, in some instances, mitigate concerns that the accused will fail to appear at proceedings for the offence.186

Variation of conditions

The power to vary bail conditions is set out in Pt 5. On an application to vary bail, the accused does not need to satisfy the show cause requirement again, but a court may undertake a fresh assessment of any relevant bail concerns and the question of unacceptable risk.187

In R v Alahmad,188 Schmidt J refused an application to vary the existing bail by removing the house arrest condition to enable the accused to undertake employment. Her Honour found the accused’s compliance with the stringent conditions did not reflect a reduced risk, but indicated the conditions had kept him from situations where he would be tempted to breach the most important bail condition, that he be of good behaviour. Similarly in R v Lazar,189 Lonergan J refused an application to vary the “commercial financial dealing” bail conditions imposed, finding they were reasonably necessary to address the bail concern that the accused would engage in further serious offending in the way he conducts commercial financial dealings, and were relevant, reasonable and proportionate to the offences for which bail was granted.

Bail and terrorism offences

Special provisions apply to bail applications made in relation to terrorism or terrorism-related offences. These are found in the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) and the Bail Act 2013.

Commonwealth position

The Commonwealth has had special provisions with respect to bail for alleged terrorism offenders since June 2004.

Section 15AA of the Crimes Act 1914, provides that there is a presumption against bail for a person charged with, or convicted of, an offence covered by s 15AA(2)190 or s 15AA(2A)191 of the Act unless the bail authority is satisfied that exceptional circumstances exist to justify bail.

If the offender is a child, when a court is determining whether exceptional circumstances exist to rebut the presumption against bail, while the best interests of the child are a primary consideration, the protection of the community is the paramount consideration: s 15AA(3AA).

NSW position

Section 22A(1) of the Bail Act 2013 provides that unless exceptional circumstances exist, a bail authority must refuse bail for:

an offence of membership of a terrorist organisation,192 or

an offence carrying a custodial penalty where the accused person

is subject to a terrorism control order, or

has a previous conviction for a terrorism offence under Commonwealth or NSW law, or

has been charged separately with a terrorism offence and the proceedings have not yet concluded.

If the offence is a show cause offence, the exceptional circumstances test applies instead of the show cause requirement in s 16A: s 22A(2).

“Exceptional circumstances”

At the time of publication of this paper, no bail decisions had been made under s 22A of the NSW Act since it came into force in December 2016. However, it was noted by the Attorney General (NSW), referring to the “exceptional circumstances” test under s 22A that “New South Wales courts may find guidance in decisions under the Commonwealth provisions”.193

The onus is on the accused to establish that exceptional circumstances exist.194 It has been recognised by the courts to be an extremely high hurdle.195 If the accused discharges that onus, the prosecution then bears the onus of establishing an unacceptable risk.196

“Exceptional circumstances” is a flexible concept.197 It cannot be determined by reference to any fixed category or class of case; regard must be had to the facts and circumstances of each case which may include the accused’s personal or subjective circumstances and the circumstances relating to the strength or weakness of the Crown case.198 The accused must demonstrate a situation which is out of the ordinary in some way and which justifies the adjective “exceptional”.199 Circumstances will not generally be exceptional unless unusual, uncommon, atypical or abnormal.200 Justice Harrison in R v Naizmand201 noted that “what are looked for are circumstances that are or that appear to be an exception to what normally or regularly occurs, whatever may be their particular or defining characteristics”.

In the Victorian case of Re Kaya,202 it was said that while delay, of itself, was capable of giving rise to exceptional circumstances, whether or not a particular length of delay was exceptional must be viewed in the particular circumstances of the case, including the nature of the charged offence. Terrorism cases of their nature are likely to be long and involved, and in Kaya the delay (in this case 18 months to 2 years) was said not to give rise to an exceptional circumstance given the case involved six co-accused.

Youth is a relevant consideration when assessing exceptional circumstances.203 Justice Hall in R v NK204 acknowledged that s 15AA(1) of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) operates notwithstanding particular State provisions relating to juveniles (including the Bail Act), but stated that an accused’s youth is a potentially important consideration in assessing exceptional circumstances under s 15AA(1), in particular the possible vulnerability of youth to adult persuasion or influence.205 Exceptional circumstances were found in R v NK206 on the basis of the accused’s vulnerability arising from youth, particularly given the material which was prima facie capable of supporting an inference that two adults sought to engage, utilise or influence the underage accused in giving effect to the enterprise or objective they had in mind.

In AB v R (Cth)207 a number of matters in combination, including a weak Crown case and a variety of subjective factors, established exceptional circumstances under s 15AA(1).

Appeal bail

Section 22(1) of the Act provides that a court must not grant or dispense with bail in respect of an offence for which an appeal is pending in the Court of Criminal Appeal or the High Court in relation to a conviction on indictment or a sentence imposed on a conviction on indictment, unless it is established that special or exceptional circumstances exist that justify the bail decision.208 While there is an open question as to whether the Supreme Court has power to grant bail where judicial review proceedings are pending in the Court of Appeal, in both Liristis v DPP (NSW)209 and Hay v DPP (NSW)210 the court was prepared to accept that such proceedings fell within the concept of “proceedings on an appeal against conviction or sentence” in s 5(1)(d) of the Act. In Hay v DPP (NSW),211 Johnson J observed that in the particular circumstances of that case, where there had been a determination on the merits in both the Local and District Courts, “the idea that such an application may proceed without the type of limitations applicable under s 22 seems problematic”.

While, for appeals, the special or exceptional circumstances test replaces the show cause requirement, the unacceptable risk test also applies to a bail decision under s 22: ss 22(2)–(3). A two-stage approach is therefore required.212

Unlike the show cause requirement, s 22 incorporates the exhaustive list of factors in s 18 that guide a consideration of unacceptable risk.213 However, the question whether there are special or exceptional circumstances is to be assessed independently of whether there is an unacceptable risk.214

Although it is likely that an applicant who establishes special and exceptional circumstances will also satisfy the unacceptable risk test, that is not a universal proposition; each test must be applied in accordance with the terms of the Act.215

To be exceptional, a circumstance need not be unique, unprecedented or very rare, but must not be a circumstance regularly, routinely, or normally encountered.216 Special or exceptional circumstances may exist as a result of a combination of factors.217 Justice Hamill noted in El-Hilli & Melville v R218 that two frequently arising factors are the merits of the appeal and the possibility that the applicant will have served the whole, or a substantial part, of their sentence or non-parole period before the appeal is determined.

The court in El Khouli v R219 noted a distinction drawn in the authorities between cases where the merit of an appeal is relied upon in isolation, and those where that factor is relied upon in combination with other factors. Where an applicant relies exclusively, or principally, on the strength of an appeal, it may be necessary to establish that the appeal is “most likely” to succeed.220 In circumstances in which the merits of an appeal are put forward together with other factors, the relevant question is whether there are “reasonable prospects of success”.221 The difficulty for a judge sitting in a bail court to make that determination has been acknowledged.222 The court is confined to reaching only a broad overall view of an applicant’s apparent prospects of success on appeal.223 In instances where special leave to appeal has been granted by the High Court, the fact leave has been granted indicates the appeal to the High Court is, at least, arguable.224

In McGlone v DPP (Cth)225 a Crown concession that one of the appeal grounds had merit, and that orders for a new trial would not be opposed, was said to be a special or exceptional circumstance. Similarly, in R v JB,226 the Crown foreshadowed a concession in the Court of Criminal Appeal that the conviction appeal be allowed which, it was conceded on the bail application, established special or exceptional circumstances.

In HT v DPP (NSW),227 a significant factor in establishing special or exceptional circumstances was the fact the applicant had already served the whole of the non-parole period imposed at first instance. Similarly, in R v Vaziri,228 where the applicant would have served a substantial part, if not all, of the non-parole period by the time of the appeal, it was noted that an acquittal on appeal “would be a hollow victory.” In Samandi v DPP (NSW),229 special or exceptional circumstances were established where, despite there being no reasonable prospects of success in respect of a conviction appeal, the unrepresented applicant’s sentence appeal was reasonably arguable, was listed for hearing shortly before his non-parole period expired and his custodial status was adversely affecting his ability to properly prepare for his appeal.

Youth may also be relevant when considering whether special or exceptional circumstances have been established, particularly given the “general policy of the criminal law, and the proper application of international instruments concerning the rights of children, militate against incarceration even where, as here, the child has pleaded guilty to serious offences”.230

Breach of bail

As already indicated in Table 1 above, notwithstanding the limitations on the Local Court’s powers identified in s 68, it is clear that s 60 empowers the court to determine a bail application following a breach of bail even if the accused has made their first appearance in another jurisdiction.231

Actions that can be taken to enforce bail requirements — s 77

The powers of a police officer with respect to the action they may take where they believe, on reasonable grounds, that there has been a breach of bail are set out in s 77(1). These include the power to issue a warning or to arrest the person without a warrant. It is preferable that a police officer first consider alternatives in s 77(1) before arresting a person for a suspected breach of bail.232 However, not every case of a failure to consider all of the options available for a breach of bail will render an arrest improper. The circumstances and facts that led to the failure to consider the other options to arrest must be taken into account. For example, if there is insufficient time in an urgent situation, it may not be improper for a police officer not to consider every other option available under s 77.233

Where bail has been granted to a person who has been sentenced to imprisonment and the execution of the sentence has been stayed in the circumstances identified in s 77A(1),234 a court may issue a warrant for the person’s arrest if they fail to appear.

Offence of fail to appear — s 79(1)

Under s 79(1), a person who, without reasonable excuse, fails to appear before a court in accordance with a bail acknowledgment is guilty of an offence. The maximum penalty available is the maximum penalty for the offence for which bail was granted, subject to the qualification that imprisonment is not to exceed 3 years and a monetary penalty is not to exceed 30 penalty units: ss 79(3)–(4). The onus is on the person granted bail to prove reasonable excuse: s 79(2).

A NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research study published in 2018,235 found around half of the bail breaches in NSW involved further offending while on bail. The most common offending being breaches of an apprehended domestic violence order (46.5%), “other driving offences” (14.6%), domestic violence-related assault (13.5%), harassment, threatening behaviour and private nuisance (12.8%) and possession and/or use of illicit drugs (10.1%). Breach of bail by further offending was strongly predictive of bail refusal, with 48.2% of defendants being refused bail where the breach involved further offending only. Where the defendant committed a technical breach only (that is, by breaching specific bail conditions) bail was refused in 19.7% of cases. The most common bail condition breached was reporting to police (18.1%).

Sentencing statistics for fail to appear offences

This section analyses sentences for offences of failing to appear (s 79(1) Bail Act 2013) in NSW courts236 between 20 May 2014237 and 30 June 2019 (the study period).238 During this period, a total of 14,425 offenders were sentenced for 20,914 fail to appear offences in NSW Courts. Table 3 shows the number of fail to appear offences finalised in each court. The vast majority of offences were finalised in the Local Court (18,993 or 90.8%)239 followed by 1,861 in the Children’s Court (8.9%). Only 60 offences were finalised in the District Court (0.3%).240 Because of this, the following analysis of penalty options is confined to the Local and Children’s Court.

Table 3. Number of fail to appear offences finalised by court

| Court | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 20914 | 100 |

| Local Court | 18993 | 90.8 |

| Children’s Court | 1861 | 8.9 |

| District Court | 60 | 0.3 |

Distribution of penalties imposed in the Local Court

On 24 September 2018, the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Amendment (Sentencing Options) Act 2017 commenced. The Act amended the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 to significantly reform the NSW sentencing regime by, inter alia, repealing a number of sentencing options available to the Local and higher courts and introducing new ones.241

Table 4 sets out the distribution of penalties imposed in the Local Court. Sentencing data for the Local Court has been separated into pre-reform and post-reform groups so that the use of particular penalty options can be examined.242 However, because of the variation in penalty options available to the court over the study period, penalty options have also been grouped at a higher level (“penalty type”) to gain a broader picture of the nature of penalties imposed for the offence.243

During the study period, the most common penalty type imposed for fail to appear offences was s 10A conviction recorded with no other penalty, accounting for 65.4% of all sentences imposed. This ranking remained the same regardless of whether the offender was sentenced before the sentencing reforms (64.5%) or after (69.7%). The next most common penalty type imposed was a fine only (10.9%), with fines being imposed 11.5% of the time before the reforms and 7.9% of the time after the reforms. Full-time imprisonment was the third most common penalty type imposed for the offence, accounting for 9.1% of all sentences imposed. A Community-based order was imposed for 7.0% of offences followed by non-conviction penalties (5.5%). Alternatives to full-time imprisonment were the least used, accounting for only 2.2% of all sentences imposed during the study period.

Table 4. Distribution of penalties imposed in the Local Court for fail to appear offencesa

| Penalty Type | Pre-reform | Post-reform | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Total | 15787 (100.0) | 3206 (100.0) | 18993 (100.0) |

| Full-time imprisonment | 1471 (9.3) | 256 (8.0) | 1727 (9.1) |

| Alternative to full-time imprisonment | 332 (2.1) | 77 (2.4) | 409 (2.2) |

Home detention244 |

9 (0.1) | - | |

Intensive correction order245 |

51 (0.3) | 77 (2.4) | |

Suspended sentence246 |

272 (1.1) | - | |

| Community-based orders | 1104 (7.0) | 229 (7.1) | 1333 (7.0) |

Community correction order247 |