What makes juvenile offenders different from adult offenders

[20-2000] Foreword

[Adam Tomison, Director, Australian Institute of Criminology, Australia’s national research and knowledge centre on crime and justice]

Responding to juvenile offending is a unique policy and practice challenge. While a substantial proportion of crime is perpetuated by juveniles, most juveniles will “grow out” of offending and adopt law-abiding lifestyles as they mature. This paper outlines the factors (biological, psychological and social) that make juvenile offenders different from adult offenders and that necessitate unique responses to juvenile crime. It is argued that a range of factors, including juveniles’ lack of maturity, propensity to take risks and susceptibility to peer influence, as well as intellectual disability, mental illness and victimisation, increase juveniles’ risks of contact with the criminal justice system. These factors, combined with juveniles’ unique capacity to be rehabilitated, can require intensive and often expensive interventions by the juvenile justice system. Although juvenile offenders are highly diverse, and this diversity should be considered in any response to juvenile crime, a number of key strategies exist in Australia to respond effectively to juvenile crime. These are described in this paper.

Introduction

Historically, children in criminal justice proceedings were treated much the same as adults and subject to the same criminal justice processes as adults. Until the early twentieth century, children in Australia were even subjected to the same penalties as adults, including hard labour and corporal and capital punishment (Carrington & Pereira 2009).

Until the mid-nineteenth century, there was no separate category of “juvenile offender” in Western legal systems and children as young as six years of age were incarcerated in Australian prisons (Cunneen & White 2007). It is widely acknowledged today, however, both in Australia and internationally, that juveniles should be subject to a system of criminal justice that is separate from the adult system and that recognises their inexperience and immaturity. As such, juveniles are typically dealt with separately from adults and treated less harshly than their adult counterparts. The United Nations’ (1985: 2) Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (the “Beijing Rules”) stress the importance of nations establishing:

a set of laws, rules and provisions specifically applicable to juvenile offenders and institutions and bodies entrusted with the functions of the administration of juvenile justice and designed to meet the varying needs of juvenile offenders, while protecting their basic rights.

In each Australian jurisdiction, except Queensland, a juvenile is defined as a person aged between 10 and 17 years of age, inclusive. In Queensland, a juvenile is defined as a person aged between 10 and 16 years, inclusive. In all jurisdictions, the minimum age of criminal responsibility is 10 years. That is, children under 10 years of age cannot be held legally responsible for their actions.

How juvenile offending differs from adult offending

It is widely accepted that crime is committed disproportionately by young people. Persons aged 15 to 19 years are more likely to be processed by police for the commission of a crime than are members of any other population group.

In 2007–08, the offending rate for persons aged 15 to 19 years was four times the rate for offenders aged more than 19 years (6,387 and 1,818 per 100,000 respectively; AIC 2010). Offender rates have been consistently highest among persons aged 15 to 19 years and lowest among those aged 25 years and over.

The proportion of crime perpetrated by juveniles

This does not mean, however, that juveniles are responsible for the majority of recorded crime. On the contrary, police data indicate that juveniles (10 to 17 year olds) comprise a minority of all offenders who come into contact with the police. This is primarily because offending “peaks” in late adolescence, when young people are aged 18 to 19 years and are no longer legally defined as juveniles.

The proportion of all alleged offending that is attributed to juveniles varies across jurisdictions and is impacted by the counting measures that police in each state and territory use. The most recent data available for each jurisdiction indicate that:

-

juveniles comprised 21% of all offenders processed by Victoria Police during the 2008–09 financial year (Victoria Police 2009);

-

Queensland police apprehended juveniles (10 to 17 year olds) in relation to 18% percent of all offences during the 2008–09 financial year (Queensland Police Service 2009);

-

juveniles comprised 16% of all persons arrested in the Australian Capital Territory during the 2008–09 period (AFP 2009);

-

18% of all accused persons in South Australia during 2007–08 were juveniles (South Australia Police 2008);

-

juveniles were apprehended in relation to 13% of offence counts in Western Australia during 2006 (Fernandez et al. 2009); and

-

in the Northern Territory during 2008–09, 8% of persons apprehended by the police were juveniles (NTPF&ES 2009).

It should be acknowledged in relation to the above that the proportion of offenders comprised by juveniles varies according to offence type. This is discussed in more detail below.

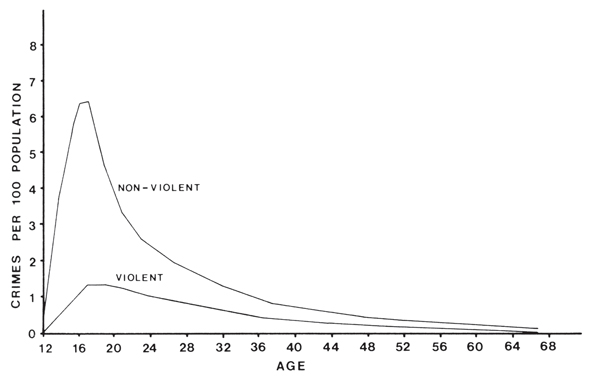

Growing out of crime: the age-crime curve

Most people “grow out” of offending; graphic representations of the age-crime curve, such as that at Figure 1, show that rates of offending usually peak in late adolescence and decline in early adulthood. Although the concept of the age-crime curve has been the subject of much debate, critique and research since its emergence, the relationship between age and crime is nonetheless “one of the most generally accepted tenets of criminology” (Fagan & Western 2005: 59). This relationship has been found to hold independently of other variables (Farrington 1986).

Juvenile offending trajectories

Research consistently indicates, however, that there are a number of different offending patterns over the life course. That is, while most juveniles grow out of crime, they do so at different rates. Some individuals are more likely to desist than others; this appears to vary by gender, for example (Fagan & Western 2005). The processes motivating desistance have not been well explored and it appears that there may be multiple pathways in and out of crime (Fagan & Western 2005; Haigh 2009).

Perhaps most importantly, a small proportion of juveniles continue offending well into adulthood. A small “core” of juveniles have repeated contact with the criminal justice system and are responsible for a disproportionate amount of crime (Skardhamar 2009).

The study of Livingstone et al (2008) of a cohort of juveniles born in Queensland in 1983 or 1984 and with one or more finalised juvenile court appearances identified three primary juvenile offending trajectories:

-

early peaking–moderate offenders showed an early onset of offending, with a peak around the age of 14 years, followed by a decline. This group comprised 21% of the cohort and was responsible for 23% of offences committed by the cohort;

-

late onset–moderate offenders, who displayed little or no offending behaviour in their early teen years, but who had a gradual increase until the age of 16 years, comprised 68% of the cohort, but was responsible for only 44% of the cohort’s offending; and

-

chronic offenders, who demonstrated an early onset of offending with a sharp increase throughout the timeframe under study, comprised just 11% of the cohort, but were responsible for 33% of the cohort’s offending (Livingstone et al 2008).

The proportion of juvenile who come into contact with the criminal justice system

Despite the strong relationship between age and offending behaviour, the majority of young people never come into formal contact with the criminal justice system. The longitudinal study by Allard et al (2010) found that of all persons born in Queensland in 1990, 14% had one or more formal contacts (caution, youth justice conference or court appearance) with the criminal justice system by the age of 17 years, although this varied substantially by Indigenous status and sex. Indigenous juveniles were 4.5 times more likely to have contact with the criminal justice system than non-Indigenous juveniles. Sixty-three per cent of Indigenous males and 28% of Indigenous females had had a contact with the criminal justice system as a juvenile, compared with 13% of non-Indigenous males and 7% of non-Indigenous females (Allard et al 2010).

The types of offences that are perpetrated by juveniles

Certain types of offences (such as graffiti, vandalism, shoplifting and fare evasion) are committed disproportionately by young people. Conversely, very serious offences (such as homicide and sexual offences) are rarely perpetrated by juveniles. In addition, offences such as white collar crimes are committed infrequently by juveniles, as they are incompatible with juveniles’ developmental characteristics and life circumstances.

On the whole, juveniles are more frequently apprehended by police in relation to offences against property than offences against the person. The proportion of juveniles who come into contact with the police for property crimes varies across jurisdictions, from almost one-third in New South Wales to almost two-thirds in Victoria (Richards 2009). Differences among jurisdictions can result from a variety of factors, including legislative definitions of offences, counting measures used to record offences and recording practices, as well as genuine differences in rates of offending. Although not available for all jurisdictions, the most recent data indicate that:

-

in Victoria during 2008–09, 66% of juvenile alleged offenders, compared with 46% of adult alleged offenders, recorded by police were apprehended in relation to property crime (Victoria Police 2009);

-

in Queensland during the same period, property offences comprised 58% of offences for which juveniles were apprehended by police, compared with 22% of offences for which adults were apprehended (Queensland Police Service 2009); and

-

in South Australia during 2007–08, property crimes comprised 46% of all crimes for which juveniles were apprehended, compared with 24% for adults (South Australia Police 2008).

Offences for which juveniles were most frequently adjudicated by the Children’s Courts in Australia during 2007–08 were acts intended to cause injury (16%), theft (14%), unlawful entry with intent (12%), road traffic offences (11%) and deception (fare evasion and related offences — also 11%; ABS 2009). Combined, these offences accounted for nearly two-thirds of defendants appearing before the Children’s Courts during this period (ABS 2009).

By comparison, offences for which adults were most frequently adjudicated in the Higher Courts during 2007–08 were acts intended to cause injury (23%), illicit drugs offences (18%), sexual assault (15%), robbery/extortion (11%) and unlawful entry with intent (9%; ABS 2009). Offences for which adults were most frequently adjudicated in the Magistrates Courts during 2007–08 were road traffic offences (45%), public order offences (11%), dangerous or negligent acts endangering persons (9%), acts intended to cause injury (8%), offences against justice procedures (6%), theft (5%) and illicit drugs offences (also 5%; ABS 2009).

The nature of juvenile offending

Juveniles are more likely than adults to come to the attention of police, for a variety of reasons. As Cunneen and White (2007) explain, by comparison with adults, juveniles tend to:

-

be less experienced at committing offences;

-

commit offences in groups;

-

commit offences in public areas such as on public transport or in shopping centres; and

-

commit offences close to where they live.

In addition, by comparison with adults, juveniles tend to commit offences that are:

-

attention-seeking, public and gregarious; and

-

episodic, unplanned and opportunistic (Cunneen & White 2007).

Some offences committed disproportionately by juveniles, such as motor vehicle theft, have high reporting rates due to insurance requirements (Cunneen & White 2007). This may result in young people coming to police attention more frequently. In addition, some behaviours (such as underage drinking) are illegal solely because of the minority status of the perpetrator. Research has demonstrated that some offence types committed disproportionately by juveniles (such as motor vehicle thefts and assaults) are the types of offences most likely to be repeated (Cottle, Lee & Heilbrun 2001).

It is also important to note that broad legislative or policy changes can disproportionately impact upon juveniles and increase their contact with the police. Farrell’s (2009) analysis of police “move on” powers clearly demonstrates, for example, that the introduction of these powers has disproportionately affected particular groups of citizens, including juveniles.

Why juvenile offending differs from adult offending

It is clear that the characteristics of juvenile offending are different from those of adult offending in a variety of ways. This section summarises research literature on why this is the case.

Risk-taking and peer influence

Research on adolescent brain development demonstrates that the second decade of life is a period of rapid change, particularly in the areas of the brain associated with response inhibition, the calibration of risks and rewards and the regulation of emotions (Steinberg 2005). Two key findings have emerged from this body of research that highlight differences between juvenile and adult offenders. First, these changes often occur before juveniles develop competence in decision making:

Changes in arousal and motivation brought on by pubertal maturation precede the development of regulatory competence in a manner that creates a disjunction between the adolescent’s affective experience and his or her ability to regulate arousal and motivation (Steinberg 2005: 69–70).

This disjuncture, it has been argued, is akin to “starting an engine without yet having a skilled driver behind the wheel” (Steinberg 2005: 70; see also Romer & Hennessy 2007).

Second, in contrast with the widely held belief that adolescents feel “invincible”, recent research indicates that young people do understand, and indeed sometimes overestimate, risks to themselves (Reyna & Rivers 2008). Adolescents engage in riskier behaviour than adults (such as drug and alcohol use, unsafe sexual activity, dangerous driving and/or delinquent behaviour) despite understanding the risks involved (Boyer 2006; Steinberg 2005). It appears that adolescents not only consider risks cognitively (by weighing up the potential risks and rewards of a particular act), but socially and/or emotionally (Steinberg 2005). The influence of peers can, for example, heavily impact on young people’s risk-taking behaviour (Gatti, Tremblay & Vitaro 2009; Hay, Payne & Chadwick 2004; Steinberg 2005). Importantly, these factors also interact with one another:

Not only does sensation seeking encourage attraction to exciting experiences, it also leads adolescents to seek friends with similar interests. These peers further encourage risk taking behavior (Romer & Hennessy 2007: 98–99).

It has been recognised that young people are more at risk of a range of problems conducive to offending — including mental health problems, alcohol and other drug use and peer pressure — than adults, due to their immaturity and heavy reliance on peer networks. Alcohol and drugs have also been found to act in a more potent way on juveniles than adults (LeBeau & Mozayani cited in Prichard & Payne 2005) and substance use is a strong predictor of recidivism (Cottle, Lee & Heilbrun 2001). As Haigh (2009) explains, adolescence is a time of complex physiological, psychological and social change. Progression through puberty has been shown to be associated with statistically significant changes in behaviour in both males and females and may be linked to an increase in aggression and delinquency (Najman et al 2009).

Intellectual disability and mental illness

Intellectual disabilities are more common among juveniles under the supervision of the criminal justice system than among adults under the supervision of the criminal justice system or among the general Australian population. Three per cent of the Australian public has an intellectual disability and 1% of adults incarcerated in New South Wales prisons was found to have an IQ below 70 in a recent study (Frize, Kenny & Lennings 2008). By comparison, 17% of juveniles in detention in Australia have an IQ below 70 (Frize, Kenny & Lennings 2008; see also HREOC 2005). Frize, Kenny and Lennings’ (2008) study of 800 young offenders on community-based orders in New South Wales found that the over-representation of intellectual disabilities was particularly high among Indigenous juveniles and that juveniles with an intellectual disability are at a significantly higher risk of recidivism than other juveniles.

Mental illness is also over-represented among juveniles in detention compared with those in the community. The Young People In Custody Health Survey, conducted in New South Wales in 2005, found that 88% of young people in custody reported symptoms consistent with a mild, moderate or severe psychiatric disorder (HREOC 2005).

Young people as crime victims

Young people are not only disproportionately the perpetrators of crime; they are also disproportionately the victims of crime (see Finkelhor et al 2009; Richards 2009). Young people aged 15 to 24 years are at a higher risk of assault than any other age group in Australia and males aged 15 to 19 years are more than twice as likely to become a victim of robbery as males aged 25 or older, and all females (AIC 2010). Statistics also show that juveniles comprise substantial proportions of victims of sexual offences. In 2007, the highest rate of recorded sexual assault in Australia was for 10 to 14 year old females, at 544 per 100,000 population (AIC 2008). For males, rates were also highest among juveniles, with 95 per 100,000 population 10 to 14 year olds reporting a sexual assault (AIC 2008).

In addition, it is important to recognise that juveniles are frequently the victims of offences committed by other juveniles. Between 1989–90 and 2007–08, almost one-third of homicide victims aged 15 to 17 years, for example, were killed by another juvenile (Richards, Dearden & Tomison forthcoming). As Daly’s (2008) research demonstrates, the boundary between juvenile offenders and juvenile victims can easily become blurred. Cohorts of juvenile victims and juvenile offenders are unlikely to be entirely discrete and research consistently shows that these phenomena are interlinked.

The high rate of victimisation of juveniles is critical to consider, as it is widely acknowledged that victimisation is a pathway into offending behaviour for some young people.

The challenge of responding to juvenile crime

Preventing juveniles from having repeated contacts with the criminal justice system and intervening to support juveniles desist from crime are therefore critical policy issues. Assisting juveniles to grow out of crime — that is, to minimise juvenile recidivism and to help juveniles become “desisters” (Murray 2009) — are key policy areas for building safer communities.

Although juvenile crime is typically less serious and less costly in economic terms than adult offending (Cunneen & White 2007), juvenile offenders often require more intensive and more costly interventions than adult offenders, for a range of reasons.

Juvenile offenders have complex needs

Juvenile offenders often have more complex needs than adult offenders, as described above. Although many of these problems (substance abuse, mental illness and/or cognitive disability) also characterise adult criminal justice populations, they can cause greater problems among young people, who are more susceptible — physically, emotionally and socially — to them. Many of these problems are compounded by juveniles’ psychosocial immaturity.

Juvenile offenders require a higher duty of care

Juvenile offenders require a higher duty of care than adult offenders. For example, due to their status as legal minors, the state provides in loco parentis supervision of juveniles in detention. Incarcerated juveniles of school age are required to participate in schooling and staff-to-offender ratios are much higher in juvenile than adult custodial facilities, to enable more intensive supervision and care of juveniles. For these reasons, juvenile justice supervision can be highly resource-intensive (New Economics Foundation 2010).

Juveniles may grow out of crime

As outlined above, many juveniles grow out of crime and adopt law-abiding lifestyles as young adults. Many juveniles who have contact with the criminal justice system are therefore not “lost causes” who will continue offending over their lifetime. As juveniles are neither fully developed nor entrenched within the criminal justice system, juvenile justice interventions can impact upon them and help to foster juveniles’ desistance from crime. Conversely, the potential exists for a great deal of harm to be done to juveniles if ineffective or unsuitable interventions are applied by juvenile justice authorities.

Juvenile justice interventions

A range of principles therefore underpin juvenile justice in Australia. These are designed to respond to juvenile offending in an appropriate and effective way.

The doctrine of doli incapax

The rate at which children mature varies considerably among individuals. Due to their varied developmental trajectories, children learn the difference between right and wrong — and between behaviours that are seriously wrong and those that are merely naughty or mischievous — at different ages. The legal doctrine doli incapax recognises the varying ages at which children mature. In Australia, juveniles aged 10 to 13 years inclusive are considered to be doli incapax. Doli incapax is a rebuttable legal presumption that a child is “incapable of crime” under legislation or common law. In court, the prosecution is responsible for rebutting the presumption of doli incapax and proving that the accused juvenile was able at the relevant time to adequately distinguish between right and wrong. A contested trial can only result in conviction if the prosecution successfully rebuts this presumption.

The principle of doli incapax has existed since at least the fourteenth century (Crofts 2003) and is supported by the United Nations’ (1989: 12) Convention on the Rights of the Child, which requires signatory states to establish “a minimum age below which children shall be presumed not to have the capacity to infringe the penal law”. There has, nonetheless, been a great deal of debate about its continued relevance (Crofts 2003; Urbas 2000) and the principle was abolished in 1998 in the United Kingdom.

Welfare and justice approaches to juvenile justice

Western juvenile justice systems are often characterised as alternating between welfare and justice models. The welfare model considers the needs of the young offender and aims to rehabilitate the juvenile. Offending behaviour is thought to stem primarily from factors outside the juvenile’s control, such as family characteristics. The justice model conceptualises offending as the result of a juvenile’s free will, or choice. Offenders are seen as responsible for their actions and deserving of punishment.

In reality, the welfare and justice models are ideal types and juvenile justice systems rarely reflect purely welfare or justice models. Instead, individual elements of the juvenile justice system in Australia reflect each of these paradigms. Even specific policies such as restorative justice conferencing (see Richards forthcoming for an overview) can be underpinned by both welfare and justice principles. As noted above, juvenile justice systems are, on the whole, more welfare-oriented than adult criminal justice systems.

Reducing stigmatisation

A range of measures aim to protect the privacy and limit the stigmatisation of juveniles. Prohibitions on the naming of juvenile offenders in criminal proceedings, for example, exist in all Australian jurisdictions (Chappell & Lincoln 2009). In each jurisdiction, except the Northern Territory, juveniles’ identities must not be made public, although exceptions are sometimes allowed. In the Northern Territory, the reverse is the case — juvenile offenders can be named, unless an application is made to suppress identifying information (Chappell & Lincoln 2009).

In some instances, juveniles’ convictions may not be recorded. This strategy aims to avoid stigmatising juveniles and assist juveniles to “grow out” of crime rather than become entrenched in the criminal justice system. In most jurisdictions, for example, juveniles who participate in a restorative justice conference and complete the requisite actions resulting from the conference (such as apologising to the victim and/or paying restitution), do not have a conviction recorded, even though they have admitted guilt. Similarly, in some jurisdictions, a juvenile can be found guilty of an offence without being convicted. In the Australian Capital Territory during the three month period from January to March 2008, 25% of juveniles who appeared before the ACT Children’s Court pleaded guilty but did not have a conviction recorded. A further 18% pleaded not guilty and did not have a conviction recorded (although no juvenile who pleaded not guilty during this period was acquitted; ACT DJCS 2008). The proportion of juveniles’ convictions that were not recorded varied by offence type, from zero percent for homicide and sexual assault offences to 100% for public order offences. Although these calculations are based on very small numbers and must be interpreted cautiously, they demonstrate the principle of avoiding the stigmatisation of juveniles. It is unknown to what extent this occurs in jurisdictions other than the Australian Capital Territory (Richards 2009).

It is important to consider in this context the extent to which juveniles’ psychosocial immaturity affects their pleading decisions in court. One study found that juveniles aged 15 years and younger are significantly more likely than older adolescents and adults to have compromised ability to act as competent defendants in court (Grisso et al 2003). One-third of 11 to 13 year olds and one-fifth of 14 to 15 year olds were found to be “as impaired in capacities relevant to adjudicative competence as are seriously mentally ill adults who would likely be considered incompetent to stand trial” (Grisso et al 2003: 356). This pattern of age differences was found to apply even when gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic status were controlled for and was evident among both juveniles who had had contact with the criminal justice system and those in the general community. This demonstrates that immaturity is a significant factor in shaping juveniles’ competence in court, irrespective of other influences.

Related to the above discussion is the theory of labelling. Labelling theory, which emerged in the 1960s, posits that young people who are labelled “criminal” by the criminal justice system are likely to live up to this label and become committed career criminals, rather than growing out of crime, as would normally occur. The stigmatisation engendered by the criminal justice system therefore produces a self-fulfilling prophecy — young people labelled criminals assume the identity of a criminal.

Labelling and stigmatisation are widely considered to play a role in the formation of young people’s offending trajectories — whether young people persist with, or desist from, crime. Avoiding labelling and stigmatisation is therefore a key principle of juvenile justice intervention in Australia.

Addressing juveniles’ criminogenic needs

Underpinned by the welfare philosophy, many juvenile justice measures in Australia and other Western countries are designed to address juveniles’ criminogenic needs. Outcomes of juveniles’ contacts with the police, youth justice conferencing and/or the children’s courts often aim to address needs related to juveniles’ drug use, mental health problems and/or educational, employment or family problems. Youth policing programs, for example, often focus on increasing juvenile offenders’ engagement with education, family or leisure pursuits. Specialty courts, such as youth drug and alcohol courts (see Payne 2005 for an overview), are informed by therapeutic jurisprudence and seek to address specific needs of juvenile offenders, rather than punish juveniles for their crimes.

Although many of the measures described in this paper — including specialty courts, restorative justice conferencing and diversion — are also available for adult offenders in Australia, this is the case to a far more limited extent. Many of these approaches are differentially applied to juveniles, whose youth, inexperience and propensity to desist from crime make these strategies especially appropriate for young people. This is also demonstrated by the range of measures that have recently emerged specifically for young adult offenders, such as Victoria’s dual-track system (under which 18 to 20 year old offenders can be detained in a juvenile rather than an adult correctional facility) and restorative justice measures that specifically target young adult offenders (People & Trimboli 2007). These measures further demonstrate the criminal justice system’s focus on helping young people desist from crime without being “contaminated” by older, life-course persistent criminals and the importance of providing constructive interventions that will assist young people to grow out of crime and adopt law-abiding lifestyles.

Diversion of juveniles

Each of Australia’s jurisdictions has legislation that emphasises the diversion of juveniles from the criminal justice system (see Table 1). Although there are variations among the jurisdictions, juveniles are often afforded the benefit of warnings, police cautions and youth justice conferences rather than being sent directly to court. As Richards (2009) shows, this is the case for about half of all juveniles formally dealt with by the police, although this proportion varies according to a number of factors, including offence type and juveniles’ age, gender and Indigenous status. Even those juveniles adjudicated in the Children’s Court are overwhelmingly sentenced to non-custodial penalties, such as fines, work orders and community supervision (ABS 2009).

|

NSW |

Young Offenders Act (1997) |

|

Vic |

Children, Youth and Families Act (2005) |

|

Qld |

Youth Justice Act (1992) |

|

WA |

Young Offenders Act (1994) |

|

SA |

Young Offenders Act (1993) |

|

NT |

Youth Justice Act 2005 |

|

ACT |

Children and Young People Act (2008) |

|

Tas |

Youth Justice Act (1997) |

In all jurisdictions’ juvenile justice legislation, detention is considered a last resort for juveniles. This reflects the United Nations’ (1989) Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Avoiding peer contagion

It is widely recognised that some criminal justice responses to offending, such as incarceration, are criminogenic; that is, they foster further criminality. It is accepted, for example, that prisons are “universities of crime” that enable offenders to learn more and better offending strategies and skills, and to create and maintain criminal networks. This may be particularly the case for juveniles, who, due to their immaturity, are especially susceptible to being influenced by their peers. As Gatti, Tremblay and Vitaro (2009: 991) argue, peer influence plays a fundamental role in orienting juveniles’ behaviour and “deviant behavior is no exception”. Separate juvenile and adult criminal justice systems were established, in part, because of the need to prevent juveniles being influenced by adult offenders (Gatti, Tremblay & Vitaro 2009).

Gatti, Tremblay and Vitaro’s (2009) longitudinal study of 1,037 boys born in Canada who attended kindergarten in Montreal, Canada in 1984, found that intervention by the juvenile justice system greatly increased the likelihood of adult criminality among this cohort. Even when the effect of other relevant variables had been controlled for, Gatti, Tremblay and Vitaro (2009) found that contact with the juvenile justice system increased the cohort’s odds of adult judicial intervention by a factor of seven. An increase in the intensity of interventions was also found to increase negative impacts later in life. The more restrictive and intensive an intervention, the greater its negative impact, with juvenile detention being found to exert the strongest criminogenic effect. Gatti, Tremblay and Vitaro (2009) therefore recommend early prevention strategies, the reduction of judicial stigma and the limitation of interventions that concentrate juvenile offenders together.

Conclusion

Juvenile offenders differ from adult offenders in a variety of ways, and as this paper has described, juveniles’ offending profiles differ from adults’ offending profiles. In comparison with adults, juveniles tend to be over-represented as the perpetrators of certain crimes (eg graffiti and fare evasion) and under-represented as the perpetrators of others (eg fraud, road traffic offences and crimes of serious violence).

In addition, by comparison with adults, juveniles are at increased risk of victimisation (by adults and other juveniles), stigmatisation by the criminal justice system and peer contagion. Due to their immaturity, juveniles are also at increased risk of a range of psychosocial problems (such as mental health and alcohol and other drug problems) that can lead to and/or compound offending behaviour.

Some of the key characteristics of Australia’s juvenile justice systems (including a focus on welfare-oriented measures, the use of detention as a last resort, naming prohibitions and measures to address juveniles’ criminogenic needs) have been developed in recognition of these important differences between adult and juvenile offenders.

It should be noted, however, that while juvenile offenders differ from adults in relation to a range of factors, juvenile offenders are a heterogeneous population themselves. Sex, age and Indigenous status, for example, play a part in shaping juveniles’ offending behaviour and criminogenic needs and these characteristics should be considered when responding to juvenile crime.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Australasian Juvenile Justice Administrators (AJJA). The author would like to acknowledge the support and assistance provided by the AJJA.

References

All URLs correct at December 2010.

Allard T et al, “Police diversion of young offenders and Indigenous over-representation” Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice (2010) no 390. https://www.aic.gov.au/en/publications/current%20series/tandi/381-400/tandi390.aspx

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Criminal courts Australia 2007–08, cat no 4513.0, Canberra, ABS, 2009.

Australian Capital Territory Department of Justice and Community Safety (ACT DJCS), ACT criminal justice statistical profile: March 2008 profile, Canberra, ACT DJCS, 2008.

Australian Federal Police (AFP), ACT policing annual report 2008–2009, Canberra, AFP, 2009.

Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC), Australian crime: facts & figures 2009, Canberra, AIC, 2010. https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current%20series/facts/1-20/2009.aspx

Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC), Australian crime: facts & figures 2007, Canberra: AIC, 2008. https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current%20series/facts/1-20/2007.aspx

Boyer T, “The development of risk-taking: a multi-perspective review”, Developmental Review (2006) 26 291–345.

Carrington K & Pereira M, Offending youth: Sex, crime and justice, Federation Press, Leichhardt, 2009.

Chappell D & Lincoln R, “‘Shhh … we can’t tell you’: an update on the naming prohibition of young offenders” Current Issues in Criminal Justice (2009) 20(3) 476–484.

Cottle C, Lee R & Heilbrun K, “The prediction of criminal recidivism in juveniles: a meta-analysis” Criminal Justice and Behaviour (2001) 28(3) 367–394.

Crofts T, “Doli incapax: why children deserve its protection” Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law (2003) 10(3). https://www.murdoch.edu.au/elaw/issues/v10n3/crofts103.html

Cunneen C & White R, Juvenile justice: youth and crime in Australia, 3rd ed, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2007.

Daly K, “Girls, peer violence, and restorative justice” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology (2008) 41(1) 109–137.

Fagan A & Western J, “Escalation and deceleration of offending behaviours from adolescence to early adulthood” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology (2005) 38(1): 59–76.

Farrell J, “All the right moves? Police ‘move-on’ powers in Victoria” Alternative Law Journal (2009) 34(1) 21–26.

Farrington D, “Age and crime” in Tonry M & Morris N (eds) Crime and justice: an annual review of research, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1986, pp 189–250.

Fernandez J, Walsh M, Maller M & Wrapson W, Police arrests and juvenile cautions Western Australia 2006, University of Western Australia Crime Research Centre, Perth, 2009.

Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R & Hamby S, “Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth” Pediatrics (2009) 125(5) 1–13.

Frize M, Kenny D & Lennings C, “The relationship between intellectual disability, Indigenous status and risk of reoffending in juvenile offenders on community orders” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research (2008) 52(6): 510–519.

Gatti U, Tremblay R & Vitaro F, “Iatrogenic effect of juvenile justice” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry (2009) 50(8) 991–998.

Grisso T et al, “Juveniles’ competence to stand trial: a comparison of adolescents’ and adults’ capacities as trial defendants” Law and Human Behavior (2003) 27(4) 333–363.

Haigh Y, “Desistance from crime: reflections on the transitional experiences of young people with a history of offending” Journal of Youth Studies (2009) 12(3) 307–322.

Hay D, Payne A & Chadwick A, “Peer relations in childhood” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry (2004) 45(1) 84–108.

Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC), Indigenous young people with cognitive disabilities and Australian juvenile justice systems: a report, HREOC, Sydney, 2005.

Livingston M, Stewart A, Allard T & Ogilvie J, “Understanding juvenile offending trajectories”, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology (2008) 41(3) 345–363.

Murray C, “Typologies of young resisters and desisters” Youth Justice (2009) 9(2) 115–129.

Najman J et al, “The impact of puberty on aggression/delinquency: adolescence to young adulthood” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology (2009) 42(3) 369–386.

New Economics Foundation (NEF), 2010. Punishing costs: how locking up children is making Britain less safe, NEF, London, 2010. https://www.neweconomics.org/sites/neweconomics.org/files/Punishing_Costs.pdf

Northern Territory Police, Fire and Emergency Services (NTPF&ES), 2009 annual report, NTPF&ES, Darwin, 2009.

Payne J, Specialty courts in Australia: report to the Criminology Research Council Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra, 2005. https://www.criminologyresearchcouncil.gov.au/reports/2005-07-payne/

People J & Trimboli L, An evaluation of the NSW community conferencing for young adults pilot program, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Sydney, 2007. https://www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/lawlink/bocsar/ll_bocsar.nsf/vwFiles/L16.pdf/$file/L16.pdf

Prichard J & Payne J, Alcohol, drugs and crime: a study of juveniles in detention, Research and public policy series no 67, Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra, 2005. https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current%20series/rpp/61-80/rpp67.aspx

Queensland Police Service, Annual statistical review 2008–09, Queensland Police Service, Brisbane, 2009.

Reyna V & Rivers S, “Current theories of risk and rational decision making” Developmental Review (2008) 28 1–11.

Richards K (forthcoming), “Restorative justice for juveniles in Australia” Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra.

Richards K, Juveniles’ contact with the criminal justice system in Australia, Monitoring report no 07, Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra, 2009. https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current%20series/mr/1-20/07.aspx

Richards K, Dearden J & Tomison (forthcoming), “Child victims of homicide in Australia” Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra.

Romer D & Hennessy M, “A biosocial-affect model of adolescent sensation seeking: the role of affect evaluation and peer-group influence in adolescent drug use” Prevention Science (2007) 8 89–101.

Skardhamar T, “Reconsidering the theory of adolescent-limited and life-course persistent anti-social behaviour” British Journal of Criminology (2009) 49 863–878.

Steinberg L, “Cognitive and affective development in adolescence” Trends in Cognitive Sciences (2005) 9(2) 69–74.

South Australia Police, Annual report 2007/2008, South Australia Police, Adelaide, 2008.

United Nations, Convention on the rights of the child, adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989. https://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/crc.htm

United Nations, United Nations standard minimum rules for the administration of juvenile justice (the Beijing rules), adopted by General Assembly resolution 40/33 of 29 November 1985. https://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/40/a40r033.htm

Urbas G, “The age of criminal responsibility” Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice (2000) no 181. https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current%20series/tandi/181-200/tandi181.aspx

Victoria Police, Crime statistics 2008/2009 Victoria Police, Melbourne, 2009.