Care and protection jurisdiction

- Note:

-

All references to sections in this chapter are, unless otherwise stated, references to sections in the Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Act 1998. Where “child” is referred to herein, the reference also includes a “young person”.

[40-000] Objects and principles of the Act

Objects

Section 8 sets out the objects of the Act:

- (a)

that children and young persons receive such care and protection as is necessary for their safety, welfare and well-being, having regard to the capacity of their parents or other persons responsible for them, and

- (a1)

recognition that the primary means of providing for the safety, welfare and well-being of children and young persons is by providing them with long-term, safe, nurturing, stable and secure environments through permanent placement in accordance with the permanent placement principles, and

- (b)

that all institutions, services and facilities responsible for the care and protection of children and young persons provide an environment for them that is free of violence and exploitation and provide services that foster their health, developmental needs, spirituality, self-respect and dignity, and

- (c)

that appropriate assistance is rendered to parents and other persons responsible for children and young persons in the performance of their child-rearing responsibilities in order to promote a safe and nurturing environment.

The Act applies to children who ordinarily live in NSW, are present in NSW, have a sufficient connection to NSW, or are subject to an event or circumstances occurring in NSW that gives rise to a report, including those outside of NSW: s 4(1), (2). Section 4(3) provides a list of factors which may be considered in determining whether a child has a sufficient connection to NSW.

The “paramountcy principle”

The paramount principle under which the Act is to be administered is that in any action or decision concerning a particular child, their safety, welfare and well-being is paramount: s 9(1).

This principle prevails over all other considerations, even where it conflicts with the rights or interests of the parents: Re Tanya [2016] NSWSC 794 at [69].

The unacceptable risk of harm test

In cases where issues such as removal, restoration, custody, placement and contact are to be determined, the proper test to be applied is that of “unacceptable risk” of harm to the child(ren) concerned: M v M (1988) 166 CLR 69 at [25]; Re Tanya, above, at [69].

The application of that test requires a determination, firstly, whether a risk of harm exists, and secondly, the magnitude of that risk: M v M, above, at [24]. Once a risk is found to exist and its magnitude is assessed, the court must balance that risk against the risk that the child may be harmed by lack of contact with the parent when determining whether the risk of harm is unacceptable: Re Hamilton [2010] CLN 2 at [45]; Re Tanya at [69].

The assessment does not require a finding, on the balance of probabilities, of facts from which an inference of unacceptable risk may be drawn. There may be several possible sources of risk, none of which is proved on the balance of probabilities, but nonetheless the accumulation of those possible risks could justify an overall finding of unacceptable risk. However, caution should be exercised before making a finding on that basis: Re Benji and Perry [2018] NSWSC 1750 at [51]–[52].

Although the High Court in M v M was concerned with the risk of harm by sexual abuse, it is well established that the “unacceptable risk” test does not arise solely in respect of allegations of physical or sexual abuse; it can include any or all matters that compromise the safety, welfare and well-being of a child, and is examined in light of an accumulation of factors proved: DFaCS (NSW) and the Colt Children [2013] NSWChC 5 at [146]–[149]; Secretary, DFaCS and the Harper Children [2016] NSWChC 3 at [32]–[33].

Additional principles to be applied

Subject to the paramount principle, other principles to be applied in the administration of the Act are (s 9(2)):

- (a)

-

the child’s views must be given due weight

- (b)

-

account must be taken of the culture, disability, language, religion and sexuality of the child and, if relevant, those with parental responsibility for the child

- (c)

-

the least intrusive intervention in the life of the child and his/her family must be taken, consistent with the paramount concern of protecting the child from harm and promoting their development

- (d)

-

children temporarily or permanently deprived of their family environment are entitled to special protection and assistance from the State, and his/her name, identity, language, cultural and religious ties should, as far as possible, be preserved

- (e)

-

arrangements for out-of-home care should be made in a timely manner; the younger the child, the greater the need for early decisions regarding permanent placement

- (f)

-

a child in out-of-home care is entitled to a safe, nurturing, stable and secure environment. Unless contrary to his/her best interests, and taking into account their wishes, this includes retention of relationships with people significant to the child (birth or adoptive parents, siblings, extended family, peers, family friends and community)

- (g)

-

if a child is placed in out-of-home care, the permanent placement principles (see below) are to guide all actions and decisions regarding permanent placement.

The principle of least intrusive intervention in s 9(2)(c) is confined to when it is necessary to take action in order to protect a child from harm. There must be a prospect of harm if action is not taken, and the question is then the nature of the action. Where the court is considering whether or not to displace existing care arrangements and return a child to the child’s family, the principle has limited application, although the preference for existing care arrangements to continue may still be a material matter: Re Tracey (2011) 80 NSWLR 261 at [79].

Australia’s treaty obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child are also relevant to determinations under the Act: Re Tracey, above, at [43]–[49]. Although the paramountcy principle is reflected in Art 3.1 of the Convention, other Articles may be relevant in determining the best interests of the child, particularly Arts 3.2, 5, 8.1, 9.1, 12.1, 29 and 30.

Principle of making “active efforts”

For applications made on or from 15 November 2023, subject to the “paramountcy principle”, functions under the Act must be in accordance with the principle of active efforts: s 9A(1), (5); Sch 3 Pt 14 cl 2(a). The “principle of active efforts” means making active efforts to prevent the child from entering out-of-home care, and in the case of removal, restoring the child to the parents, or if not practicable or in the child’s best interests, with family, kin or community: s 9A(2). Active efforts are to be timely, practicable, thorough and culturally appropriate, amongst other things, and can include providing, facilitating or assisting with access to support services and other resources — considering alternative ways of addressing the needs of the child, family, kin or community: s 9A(3), (4).

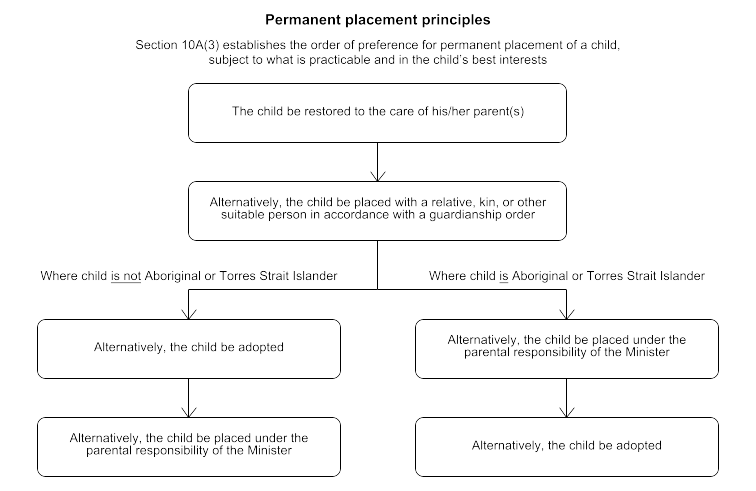

Permanent placement principles

Section 10A(1) defines “permanent placement” as “a long-term placement following the removal of a child or young person from the care of a parent or parents pursuant to this Act that provides a safe, nurturing, stable and secure environment for the child or young person”.

Subject to ss 8 and 9, a child in need of permanent placement is to be placed in accordance with the permanent placement principles: s 10A(2). Section 10A sets out a hierarchy to prioritise the placement of children with family: A v Secretary, Family and Community Services [2015] NSWDC 307 at [473]–[476].

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander principles

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Principles are enshrined in Ch 2, Pt 2 of the Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Act.

Section 11(1) provides that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are to participate in the care and protection of their children with as much self-determination as is possible.

Section 12A(2) sets out the five elements which make up the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children and Young Persons Principle: (a) prevention; (b) partnership; (c) placement; (d) participation, and (e) connection, which apply to the administration of the Act, as relevant to the decision being made, in relation to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young persons: s 12A(1), (3).

These are aimed at enhancing and preserving Aboriginal children’s sense of identity, as well as their connection to their culture, heritage, family and community: Second Reading Speech, Legislative Council, Family is Culture Review Report 2019, p 250.

Proper implementation of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Principles requires an acknowledgement that the cultural identity of an Aboriginal child is “intrinsic” to any assessment of what is in the child’s best interests: The Secretary of the Department of Communities and Justice and Fiona Farmer [2019] NSWChC 5 at [116]–[117].

Particular principles regarding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and their special heritage are enunciated by s 13 and are reflected particularly in ss 78(2A), 78A(4), 83(3A), 83A. Broadly speaking, these principles provide that if Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are to be removed from their parents, they should be placed with (s 13(1)):

-

extended family members or, at least

-

members of their community or, if that is not practical

-

other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons residing nearby or, as a last resort

-

a suitable person(s) approved by DCJ after consultation with members of the extended family and appropriate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations.

Section 5 provides the relevant definitions in relation to the identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. The decision of Hackett (a pseudonym) v Secretary, DCJ [2020] NSWCA 83, although relating to the Adoption Act 2000, provides guidance in respect of the application of s 5. “There is no requirement in order … to be an Aboriginal child for the child to have a specified proportion of genetic inheritance” and “descent is different from race”: Hackett per Leeming JA at [53]; [86]; Adoption Act, s 4(1), (2).

The late identification, or the de-identification, of children by DCJ can have consequences for planning and placement so, in cases where identification is an issue, the court will be assisted by timely evidence from the parties.

If a child has one Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parent and one non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parent, the child may be placed with the person with whom the best interests of the child will be served having regard to the principles of the Act: s 13(4). Arrangements must be made to ensure the child has the opportunity for continuing contact with the other parents’ family, community and culture: s 13(5).

In determining placement, account is to be taken of the child’s expressed wishes and whether they identify as an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person: s 13(2).

In relation to placement with non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons, no final order allocating sole parental responsibility for an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child to a non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person may be made except after extensive consultation and with the express approval of the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and the Minister for Community Services: s 78A(4).

Section 83A(3) provides, for care applications made on or after 15 November 2023, that a permanency plan for an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child must comply with permanent placement principles, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child and Young Persons Principle and the placement principles under s 13. The plan must also include a cultural plan that sets out how the child will maintain and develop connection with family, community and identity: s 83A(3)(b). For earlier applications, see former s 78A(3). For further information, see [40-080] Court’s consideration of care and permanency plans.

Further, if an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child is placed with a non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carer, the following principles are to determine the choice of a carer (s 13(6)):

- (a)

subject to the child’s best interests, a fundamental objective is to be the reunion of the child with his/her family or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community

- (b)

continuing contact must be ensured between the child and his/her Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family, community and culture.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander placement principles under s 13 are an aspect of the important principle in s 9(2)(d) that a child’s cultural ties should be preserved when they are removed from their family. However, s 13(1) must not be blindly implemented without regard to the principle of paramountcy and the other objects and principles set out in ss 8 and 9: Re Victoria and Marcus [2010] CLN 2. In the exceptional case of Re Victoria and Marcus, the children were placed with carers who were not Aboriginal rather than their Aboriginal grandparents as the court found there was a real risk the grandparents would actively discourage the children from identifying with their Aboriginal cultural links, “contrary to the whole purpose and spirit of the Aboriginal Placement Principles set out in s 13(1)”: at [52].

The principles in s 13(1) do not apply to emergency placements to protect a child from serious risk of immediate harm, or to a placement of less than two weeks duration: s 13(7).

[40-020] Applications

Emergency care and protection order (s 46)

In situations where there is an urgent need to protect a child, FACS can apply to the court for an emergency care and protection order (ECPO). If satisfied that a child is at risk of serious harm, the court may make an ECPO: s 46(1). The order, while in force, places the child in the care of the Secretary or person specified in the order: s 46(2).

If the child has been removed without warrant, or care is assumed by an order under s 44, the application must be made within three working days after the day on which removal or assumption of care: s 45(1A).

An ECPO has effect for a maximum of 14 days: s 46(3). However, it may be extended once only for a further maximum period of 14 days: s 46(4).

Care order (s 61)

An application for a care order must be commenced by the Secretary: s 61(1). It must specify the particular care order sought and the ground(s) under s 71(1) on which it is sought: s 61(1A); see below at [40-060] Grounds — s 71(1).

When making a care application the Secretary must:

-

provide a written report which summarises the facts, matters and circumstances on which the application relies and states whether or not the child is currently the subject of an order made by the court in the exercise of its jurisdiction under the Act (or by any other court exercising jurisdiction with respect to the custody or guardianship of children or parental responsibility for children): s 61(2); Children’s Court Rule 2000, r 21. See also Children’s Court Practice Note 2 “Initiating Reports and Service of the relevant portion of the Community Services file in Care Proceedings”

-

for care applications made on or after 15 November 2023, provide evidence of active efforts made to take alternative action in accordance with s 9A and the reasons why active efforts were unsuccessful; and provide evidence that alternatives to a care order were considered by the Secretary and the reasons why the alternatives were not considered appropriate: s 63(1); Sch 3 Pt 14 cl 2(b). This includes evidence that, before making the care application, active efforts were made to provide, facilitate or assist with support for the child and their parents’ safety, welfare and well-being, and that a parent responsibility contract, a parent capacity order, a temporary care arrangement and alternative dispute resolution were considered: s 63(2). Active efforts are not applicable when seeking an emergency care and protection order: s 63(3). If the court is not satisfied with the evidence, then neither the dismissal of the care application nor the discharge of the child to the care responsibility of the Secretary should be taken, unless in the best interests of the child’s safety, welfare and well-being: s 63(5),

-

for care applications made before 15 November 2023, see former s 63(1).

Applications for guardianship order (s 79B)

Despite the restriction under s 61(1) that a care application only be made by the Secretary, an application for a guardianship order may be made by the Secretary, or (with the Secretary’s written consent) either the agency responsible for supervising the placement of the child, or a person who is seeking to be allocated all aspects of parental responsibility for the child (including an authorised carer): s 79B(1).

The Secretary must not make, or consent to, an application unless satisfied that the person to whom parental responsibility is to be allocated has agreed to undergo, and has satisfied, the suitability assessments prescribed by cl 3 and Sch 2 Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Regulation 2022: s 79B(1A).

Interim orders

Interim care orders may be made after a care application is made and before the application is finally determined (s 69), and prior to the determination of whether a child is in need of care and protection, where the court is satisfied it is appropriate to do so: s 69(1A). An interim order is of a temporary or provisional nature pending final resolution of the proceedings, and an applicant generally speaking does not have to satisfy the court of the merits of its claim: Re Jayden [2007] NSWCA 35 at [74]–[75].

When seeking an interim care order, the Secretary has the onus of satisfying the court that it is not in the best interests of the child’s safety, welfare and well-being that he or she should remain with his or her parents or other persons having parental responsibility: s 69(2).

Other forms of interim orders may be made if the court considers them appropriate for the safety, welfare and well-being of a child, pending the conclusion of the proceedings: s 70.

An interim care order should not be made unless the court is satisfied that making the order is necessary in the interests of the child, and is preferable to making a final order or dismissing the proceedings: s 70A.

When applying the relevant tests under ss 69, 70 and 70A, the court may be satisfied simply by weighing the risks involved on the evidence available to it at the time (cf M v M (1988) 166 CLR 59): Re Jayden, above, at [79].

The usual interim order is for the allocation of parental responsibility to the Minister until further order: Re Mary [2014] NSWChC 7 at [27]. See Orders allocating parental responsibility (s 79) at [40-100].

[40-040] Hearings — practice and procedure

General nature of proceedings

Expeditious and non-adversarial

Children’s Court proceedings are not be conducted in an adversarial manner: s 93(1). They are to be conducted with as little formality and legal technicality and form as circumstances permit: s 93(2).

The intended purpose of not conducting the proceedings in an adversarial manner is to give effect to the paramountcy principle. Adversarial proceedings, pitting parents against each other or against another carer, would not promote the paramount interests of the child and may actually harm the child by poisoning future relationships between parties who will continue to maintain contact with the child. The risks to ongoing relationships if proceedings are conducted in an adversarial manner are self-evident and well understood: D v C (No 2) [2018] NSWCA 310 at [41].

All matters are to proceed as expeditiously as possible: s 94(1). For that purpose, the court is to set a timetable for each matter taking into account the child’s age and developmental needs, and may give such directions as it considers appropriate to ensure the timetable is kept: s 94(2)–(3).

See Children’s Court Practice Note 5 “Case management in care proceedings”, 16.6 for Standard directions.

The granting of adjournments should be avoided to the maximum extent possible. Adjournments must only be granted if the court is of the opinion that it is either in the best interests of the child, or there is some other cogent or substantial reason to do so: s 94(4).

Rules of evidence not applicable

The court is not bound by the rules of evidence unless it determines that the rules should apply in relation to particular proceedings, or particular parts of proceedings: s 93(3). The court may, upon application by a party to the proceedings, determine that rules of evidence are to apply in relation to the proof of a fact if, in the court’s opinion, proof of that fact is or will be significant to the determination of part/all of the proceedings: s 93(3A).

However, the court must be careful and examine the sources of evidence, particularly quasi-opinion and secondary evidence, to determine its strength and the weight to be given to it: LZ v FACS [2017] NSWDC 414 at [150].

Standard of proof

The standard of proof is proof on the balance of probabilities: s 93(4). The Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 principle is relevant in determining whether the burden of proof, on the balance of probabilities, has been achieved: Re Sophie [2008] NSWCA 250 at [48], [50].

Appearance and legal representation

Persons with the opportunity to be heard

The court must not make an order that has a significant impact on a person who is not a party to proceedings unless the person has been given an opportunity to be heard on the matter of significant impact: s 87(1).

If the impact of the order is on a group of persons, s 87(2) provides that only one representative of the group, approved by the Children’s Court, is to be given the opportunity to be heard. If the group affected is an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander family or community, the representative may be a member of a relevant Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander organisation or entity: s 87(2A).

However, the opportunity to be heard afforded by s 87 does not give the person who is heard the status or rights of a party to the proceedings: s 87(3).

Persons with the right to appear

Pursuant to s 98(1), in any proceedings with respect to a child, the following persons may appear in person or be legally represented or, by leave of the court, be represented by an agent, and may examine and cross-examine witnesses on matters relevant to the proceedings:

-

the child and each person with parental responsibility for the child

-

the Secretary,

-

the Minister.

Further, any other person who, in the court’s opinion, has a genuine concern for the safety, welfare and well-being of the child may, by leave, appear in the proceedings, or be legally represented, or be represented by an agent, and may examine and cross-examine witnesses on matters relevant to the proceedings: s 98(3).

Justice Slattery, considering the distinction between the rights afforded by ss 87 and 98 in Bell-Collins Children v Secretary, DFaCS [2015] NSWSC 701, noted that one of the differences in focus between s 87(1) and s 98(3) is marked out by the differing thresholds that must be passed in order to enliven each section. While s 87(1) focuses on the “impact on a person”, s 98(3) is more child-centred. Persons meriting leave under s 98(3) will sometimes be people who, by their participation, can fill an evidentiary gap in the proceedings that it may be in the best interests of the child to see filled: at [33]–[34].

Representation of the child

The court may appoint a legal representative for the child: s 99(1). Such an appointment is deemed to have been made to a Legal Aid solicitor or barrister on the filing of a care application: Children’s Court Practice Note 5 “Case management in care proceedings”, 10.1.

Section 99A provides that a legal representative for a child is to act as a:

-

direct legal representative if the child is capable of giving proper instructions and a guardian ad litem has not been appointed, or

-

independent legal representative if the child is not capable of giving proper instructions, or a guardian ad litem has been appointed.

The following rebuttable presumptions apply:

-

a child less than 12 years is not capable of giving proper instructions: s 99B(1)

-

a child not less than 12 years is capable of giving proper instructions [this presumption is not rebutted merely because the child has a disability]: s 99C(1).

The following table compares the role of direct and independent legal representatives as provided, without limitation, by s 99D.

| Role of direct legal representative (DLR): s 99D(a) | Role of independent legal representative (ILR): s 99D(b) |

| Ensuring the child’s views are placed before the court | Acting on the instructions of the guardian ad litem [where appointed] |

| Ensuring all relevant evidence is adduced and, where necessary, tested | Interviewing the child |

| Acting on the instructions of the child | Explaining the role of an ILR to the child |

| Presenting direct evidence to the court about the child and matters relevant to their safety, welfare and well-being | |

| Presenting evidence of the child’s wishes (although not bound by the child’s instructions in this regard) | |

| Ensuring all relevant evidence is adduced and, where necessary, tested | |

| Cross-examining parties and their witnesses | |

| Making applications and submissions to the court for orders considered appropriate in the child’s interests | |

| Lodging an appeal if considered appropriate |

In considering the distinction between the two forms of representation, the court in Re Sally [2011] NSWSC 1696 noted that “the critical difference … is that the Direct Legal Representative acts on instructions of the child but the Independent Legal Representative exercises a degree of independent judgment about what is in the child’s … best interests in setting the course on behalf of the child before the Court”: at [12].

Guardians ad litem

The court may appoint a guardian ad litem for a child if it is of the opinion that there are special circumstances warranting, and the child will benefit from, the appointment: s 100(1).

Special circumstances may include that the child has special needs because of age, disability or illness, or that the child is, for any reason, not capable of giving proper instructions to a legal representative: s 100(2).

The functions of a guardian ad litem are to safeguard and represent the child’s interests, and to instruct the child’s legal representative: s 100(3). Where a guardian ad litem has been appointed, the child’s legal representative is to act on their instructions: s 100(4).

In addition, if the court is of the opinion that the parent(s) of a child is incapable of giving proper instructions to their representative, they may appoint a guardian ad litem for either or both parents, or request the parent’s legal representative act as amicus curiae: s 101(1).

See Department of Human Services v Kieran; Siobhan; Robert Isaac [2010] CLN 1, in which Marien DCJ held that for children of tender years, it is unlikely that special circumstances under s 100(1) would exist, but most importantly, it is highly unlikely that the appointment of a guardian ad litem (and in the context of that case, an Aboriginal guardian ad litem), would benefit the child over and above the benefits derived from the appointment of an independent legal representative: at [30].

Explanation of proceedings

The court must take such measures as are reasonably practicable, taking into account the child’s age and developmental capacity, to ensure the child understands the proceedings, in particular the nature of any assertions made in the proceedings and the legal implications of any such assertion: s 95(1).

For the purpose of enabling the court to perform its duties under s 95(1), the court may request the child’s legal representative advise it of the steps taken to ensure the child understands the necessary aspects of the proceedings: Children’s Court Practice Note 5 “Case management in care proceedings”, 21.1.

Support persons

Any participant in proceedings before the court may, with leave, be accompanied by a support person: s 102(1). Leave must be granted unless:

-

the support person is a witness

-

the court is of the opinion, having regard to the child’s wishes, leave should not be granted, or

-

there is some other substantial reason not to grant leave: s 102(2).

Persons excluded from proceedings

Sections 104–104C deal with exclusions of certain persons from the proceedings, as set out in the table below:

|

Provision |

Relevant person |

Court’s power |

|---|---|---|

|

s 104 |

The child the subject of the proceedings |

May be directed by court:

Only if, in the court’s opinion, the prejudicial effect of excluding the child is outweighed by the psychological harm likely to be caused if the child remained present. |

|

s 104A |

Any person (other than the child) [even if directly interested in the proceedings] |

May be directed by court:

Only if, in the court’s opinion, such a direction is in the interests of the child |

|

s 104B |

Any person not directly interested in the proceedings |

Must be excluded unless the court otherwise directs |

|

s 104C |

News media |

Entitled to enter and remain unless court otherwise directs |

Publication of names and identifying information

Section 105 prohibits publication or broadcast of certain information in any form that may be accessible by a person in NSW (whether before, during or after proceedings). This includes the name of a child who is the subject of the proceedings, is or is likely to be a witness, mentioned or otherwise involved in any capacity in the proceedings, or who is the subject of a report under the Act: s 105(1).

It is also prohibited to express the name of any child in a way that identifies them as being or having been under the parental responsibility of the Minister or in out-of-home care, for example by identifying them as a foster child or as a ward of the State: s 105(1AA).

The prohibition includes any information, picture or other material that is likely to lead to identification: s 105(4).

Exceptions apply, such as where a young person consents, where the court consents, or where the Minister with parental responsibility consents: s 105(3).

Examination and cross-examination of witnesses

A Children’s Magistrate is entitled to examine and cross-examine a witness to any proceedings to the extent deemed proper for the purpose of eliciting the information relevant to the exercise of the court’s powers: s 107(1).

The court must forbid offensive, scandalous, insulting etc questions, and oppressive or repetitive examination, unless satisfied it is essential in the interests of justice for the examination to continue or for the question to be answered: s 107(2)–(3). Questions to a witness, who is a parent or primary care-giver of a child, the subject of a care application, concerning the witness’s previous history of dealings with any child, are taken not to be intrinsically offensive, scandalous or oppressive: s 107(3A).

Views of siblings

The court has a discretion to obtain and consider the views of any siblings of a child with respect to whom proceedings are brought and must take account of the interests of any siblings in determining what orders (if any) to make in the proceedings: s 103.

[40-060] The “establishment” phase

Determination — “child in need of care and protection”

A final care order may only be made if the court is satisfied that the child is in need of care and protection, pursuant to either ss 71 or 72. Satisfaction of one of these two bases for making a care order is commonly described as the “establishment issue” or “establishment phase” of proceedings: Re Alistair [2006] NSWSC 411 at [65]; SB v Parramatta Children’s Court [2007] NSWSC 1297 at [44].

Section 71 provides a number of grounds on which the court can find that the child is in need of care and protection (see Grounds — s 71(1) below). The reasons identified in s 71(1) are not merely facts or particulars but are grounds, at least one of which the court must be satisfied before a care order is made: SB v Parramatta Children’s Court, above, at [51].

By contrast, s 72(1) provides that a care order may only be made if the court is satisfied either that the child “is in need of care and protection” (the s 71 criterion) or, in the alternative, that the child is “not then in need of care and protection”, but:

- (a)

was in need of care and protection when the circumstances that gave rise to the care application occurred or existed, and

- (b)

would be in need of care and protection but for the existence of arrangements for the care and protection of the child made under ss 39A, 49, 69 or 70.

Read together, ss 71 and 72 provide alternative bases for making a care order. The alternative created by s 72(1) is relevant and applicable only when the court is not satisfied there is an existing need for care and protection. The court must be satisfied that, despite the absence of existing need, both the circumstances identified in paragraphs (a) and (b) of s 72(1) exist: VV v District Court of NSW [2013] NSWCA 469 at [19]–[20].

If the court is not satisfied of either basis for a need for care and protection, it may dismiss the application: s 72(2).

Presumption — previous removal of another child

Section 106A(1) obliges the court to admit any evidence adduced that a parent or care-giver of a child, the subject of a care application, (a) has previously had a child removed from, and not restored to, their care and protection, or (b) is a person named or otherwise identified by the coroner or police as having been involved in causing a reviewable death of a child or young person. Evidence under s 106A(1)(b) is prima facie evidence that the child, the subject of the application, is in need of care and protection: s 106A(2).

The presumption in s 106A(2) may be rebutted if the court is satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that the parent or primary care-giver was not involved in causing the relevant reviewable death of the child or young person: s 106A(3).

The presumption under s 106A is not itself a ground for making a care order: SB v Parramatta Children’s Court at [49]–[51]; RC v Director-General, DFaCS [2014] NSWCA 38 at [43].

Grounds — s 71(1)

Section 71(1) sets out the grounds on which a care order may be made:

- (a)

there is no parent available to care for the child as a result of death or incapacity or for any other reason,

- (b)

the parents acknowledge that they have serious difficulties in caring for the child and, as a consequence, the child is in need of care and protection,

- (c)

the child has been, or is likely to be, physically or sexually abused or ill-treated,

- (d)

the child’s basic physical, psychological or educational needs are not being met, or are likely not to be met, by his or her parents or primary care-givers,

- Note:

the court cannot conclude the child’s basic needs will likely not be met only because of a parent or primary care-giver’s disability or poverty: s 71(2)

- (e)

the child is suffering or is likely to suffer serious developmental impairment or serious psychological harm as a consequence of the domestic environment in which he or she is living,

- (f)

in the case of a child who is under the age of 14 years, the child has exhibited sexually abusive behaviours and an order of the Children’s Court is necessary to ensure his or her access to, or attendance at, an appropriate therapeutic service,

- (g)

the child is subject to a care and protection order of another State or Territory that is not being complied with,

- (h)

s 171(1) applies in respect of the child [the Secretary has requested that the child be removed from statutory or supported out-of-home care].

The court may make a care order for a reason not listed under s 71(1), but only if it was pleaded by the Secretary in the care application: s 71(1A).

[40-080] The “placement” or “welfare” phase

Assessment orders — referral to Children’s Court Clinic

Section 53(1) permits the court to order the physical, psychological, psychiatric or other medical examination and/or assessment of a child. If they have sufficient understanding to make an informed decision, the child may refuse to submit to an examination or assessment: s 53(4).

The court may also appoint a person to assess the capacity of a person who has, or is seeking, parental responsibility for the child: s 54(1). An assessment may only be carried out with the person’s consent: s 54(2).

Assessment orders may be made on the application of the Secretary (at any time), or by a party to a care application: s 55(1). The Act does not provide for the court to make an assessment order on its own initiative: Re M (No 5) — BM v Director-General, DFaCS [2013] NSWCA 253 at [128].

Applications for assessment orders under s 53 or s 54 should be filed as soon as possible after establishment: Children’s Court Practice Note 5 “Case management in care proceedings”, 16.6.2(a). See also Children’s Court Practice Note 6 “Children’s Court Clinic assessment applications and attendance of Authorised Clinicians at hearings, dispute resolution conferences and external mediation conferences” which contains procedures for the making of assessment applications.

In determining whether to make an assessment order, the court must have regard to (s 56(1)):

- (a)

whether the proposed assessment is likely to provide relevant information that is unlikely to be obtained elsewhere,

- (b)

whether any distress the assessment is likely to cause the child or young person will be outweighed by the value of the information that might be obtained,

- (c)

any distress already caused to the child or young person by any previous assessment undertaken for the same or another purpose,

- (d)

any other matter the Children’s Court considers relevant.

The court must also ensure a child is not subjected to unnecessary assessment: s 56(2).

If the court makes an assessment order it is to appoint the Children’s Court Clinic to prepare and submit the report, unless the Clinic informs the court that it is unable to do so or considers it is more appropriate for another person to do so: s 58(1). If the Clinic so informs the court, the court is to appoint another person whose appointment, so far as possible, is agreed to by the child, the parents and the Secretary: s 58(2).

Section 58 is absolute in its terms. The discretion as to whether it is appropriate that the Children’s Court Clinic, or some independent person, make the assessment is vested in the Clinic rather than in the court. Therefore, an order for an assessment report which does not appoint the Clinic in compliance with s 58(1) will be invalid: Re Oscar [2002] NSWSC 453 at [13]–[14].

An assessment report submitted to the court is taken to be a report to the court, rather than evidence tendered by a party: s 59.

Dispute resolution

Before or at any stage during a hearing, the court may refer a care application to a Children’s Registrar for the Registrar to arrange and conduct a dispute resolution conference (DRC): s 65. The purpose of a DRC is to give parties an opportunity to agree on action that should be taken in the best interests of the child: s 65(2). As far as practicable, a DRC should be held as early as possible in the proceedings: Children’s Court Practice Note No 3, “Alternative dispute resolution procedures in the Children’s Court”, 11.1.

DRC’s are conducted using a conciliation model, with the Registrar acting as conciliator: s 65(2A).

The court may also make an order under s 65A(1) that the parties to a care application participate in an alternative dispute resolution process (external ADR). It may do so on its own initiative or on the application of a party: s 65A(2).

Section 244B provides that the following, where made during the course of, or prepared for the purposes of, a DRC or external ADR, are not admissible in any proceedings unless the persons participating, or identified, consent to admission:

-

evidence of anything said or any admission

-

the conduct of any party

-

any document.

Further, a person who conducts or participates in a DRC or external ADR must not disclose anything said or done or any admission made during the process to any other person (s 244C), except in certain circumstances permitted by s 244C(2)–(4).

Care plans and permanency planning

Care plans

Once a child is found to be in need of care and protection, and an order is sought for removal of the child from the care of his or her parents, it becomes the responsibility of the Secretary to prepare a care plan: s 78(1). A care plan must also be prepared by an applicant for a guardianship order: s 79B(8).

A court must not make a final order for removal of a child or for the allocation of parental responsibility for the child unless a care plan has been considered: s 80.

Section 78(2) provides that the care plan must make provision for the following:

- (a)

allocation of parental responsibility between the Minister and the parents for the duration of any period for which the child is removed from the care of the parents,

- (b)

the kind of placement proposed, including:

- (i)

how it relates in general terms to permanency planning for the child, and

- (ii)

any interim arrangements proposed for the child pending permanent placement and the timetable proposed for achieving a permanent placement,

- (c)

arrangements for contact between the child and parents, relatives, friends and other persons with whom they are connected,

- (d)

the agency designated to supervise the placement in out-of-home care,

- (e)

the services that need to be provided to the child.

It must also contain information about the child’s circumstances such as their family structure, history, development and experience, relationship with their parents, cultural background, etc. See further Children and Young Person (Care and Protection) Regulation 2022, cl 10 and Sch 3.

Further matters are also required to be set out pursuant to Sch 3 of the Regulation, including resources required, roles and responsibilities of each person, agency or body participating, and the frequency and means by which the progress of the plan will be assessed.

Section 78(3) provides that the care plan “is to be made as far as possible with the agreement of the parents of the child”. In context, the expression “as far as possible” requires the Secretary to assess what is possible by reference not merely to the wishes of the parents, but to the objects of the Act and the circumstances which have generated the application for removal of the child from the parents’ care: Re M (No 5) — BM v Director-General, DFaCS, above, at [133].

If a care plan made on or after 15 November 2023 is for an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child, it must include a cultural plan to show how the connection with First Nation’s family, community and identity will be maintained and developed: s 78(2A)(a), Sch 3, Pt 14 cl 2(c). The plan must be developed in consultation with the child, their parents, family and kin, and relevant First Nation’s organisations and entities: s 78(2A)(b). The plan must comply with permanent placement principles, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children and Young Persons Principles and the placement principles for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children under s 13: s 78(2A)(c). For earlier applications, see former s 78A(3).

The care plan is to be in the form approved by the Secretary in consultation with the Children’s Court Advisory Committee and regulations: s 78(5) and (6).

See further Court’s consideration of care and permanency plans, below, at [40-080].

Permanency planning

“Permanency planning” refers to the making of a plan that aims to provide a child with a stable placement that offers long-term security and:

-

has regard, in particular, to the principles set out in s 9(2)(e) and (g)

-

meets the child’s needs

-

avoids the instability and uncertainty arising through a succession of different placements or temporary care arrangements: s 78A(1).

Where the Secretary makes a care application seeking removal of the child, it must prepare a permanency plan and submit it to the court for consideration: s 83.

A care plan is required to provide how the placement sought relates to the permanency planning of the child: s 78(2)(b)(i). Therefore, in practice, the care plan incorporates the permanency plan required by s 83: Re M (No 5) — BM v Director-General, DFaCS at [107].

Realistic possibility of restoration?

The Secretary is required to assess whether there is a realistic possibility of the child being restored to his or her parents within a reasonable period: s 83(1). A “reasonable period” is no more than 24 months: s 83(8A).

There are two limbs involved in the assessment of whether there is a realistic possibility of restoration, as prescribed by s 83(1). This requires regard to be given to:

- (1)

the child’s circumstances, and

- (2)

evidence, if any, that the parent(s) are likely to be able to satisfactorily address the issues that led to the removal of the child from their care.

The requirement that the possibility of restoration be “realistic” was clearly inserted to require that the possibility of restoration be real or practical and not fanciful, sentimental or idealistic, or based upon “unlikely hopes for the future”: Re Saunders and Morgan v Department of Community Services [2008] CLN 10 at [13]–[14]; endorsed in In the matter of Campbell, above, at [56]. The concept is not to be confused with the mere hope that a parent’s situation might improve: Re Tanya [2016] NSWSC 794 at [69].

The words “within a reasonable period” in s 83 enable the court to take into account future likely events which might occur within a reasonable period. The court may consider whether a parent has already commenced a process of improving his or her parenting, and whether there has already been some significant success which enables a confident assessment that continuing success might be predicted: DFaCS v The Steward Children [2019] NSWChC 1 at [33].

Depending on the Secretary’s assessment, the permanency plan must provide for either restoration or another suitable long-term placement: s 83(2)–(3). A plan prepared under s 83(3), for a care application made on or after 15 November 2023, must include the reasons why there is no realistic possibility of restoration within a reasonable period, and details of active efforts made to restore the child to their parents or, if not practicable or in the child’s best interests, to their family, kin or community: s 83(3A); Sch 3, Pt 14 cl 2(f). For earlier applications, see former s 78A(3).

Where the permanency plan provides for restoration, it must include (s 84(1)):

- (a)

a description of the minimum outcomes the Secretary believes must be achieved before it would be safe for the child or young person to return to his or her parents,

- (b)

details of the services the Department is able to provide, or arrange the provision of, to the child or young person or his or her family in order to facilitate restoration,

- (c)

details of other services that the Children’s Court could request other government departments or funded non-government agencies to provide to the child or young person or his or her family in order to facilitate restoration,

- (d)

a statement of the length of time during which restoration should be actively pursued.

A permanency plan need not provide details as to the exact placement of the child in the long-term but must be sufficiently clear and particularised so as to provide the court with a reasonably clear picture as to the way in which the child’s needs, welfare and well-being will be met in the foreseeable future: s 78A(2A).

Permanency planning and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander considerations

For care applications made on or after 15 November 2023, s 83A sets out the requirements for the preparation of a permanency plan for an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child: Sch 3 Pt 14 cl 2(g). For earlier applications, see former s 78A(3).

Further, if a plan indicates an intention to provide permanent placement of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child through adoption by a non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person, certain requirements under s 78A(4) must be met.

See further, above, at [40-000] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander principles.

Court’s consideration of care and permanency plans

The court’s obligations to consider care and permanency plans may be summarised as follows:

-

the court cannot make a final order for removal of a child or allocating parental responsibility unless it has first considered a care plan presented by the Secretary: s 80

-

the court must decide whether to accept the Secretary’s assessment of whether or not there is a realistic possibility of restoration within a reasonable period: s 83(5A). Before making this determination, for care applications made on or after 15 November 2023, the court may direct the Secretary to provide the reasons why restoration within a reasonable period is not possible, and evidence of the active efforts made to restore the child to the parents, or, if not practicable or in the best interests of the child, to family, kin or community: s 83(5B); Sch 3 Pt 14 cl 2(f). For earlier applications, see former s 83. (Further, if the Secretary’s assessment is not accepted, the court may direct the Secretary to prepare a different permanency plan: s 83(6))

-

the court must not make a final order unless it expressly finds (s 83(7)):

- (i)

-

permanency planning for the child has been appropriately and adequately addressed, and

- (ii)

-

if the permanency plan involves restoration, that there is a realistic possibility of restoration within a reasonable period,

-

for care applications made on or after 15 November 2023, s 83A sets out the requirements for the preparation of a permanency plan for an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child: Sch 3 Pt 14 cl 2(g). For earlier applications, see former s 83.

Permanency planning was found not to have been appropriately and adequately addressed as required by ss 78A(2A) and 83(7A) in Re Hamilton [2010] CLN 2. In that case, the three children each had special needs. At the time the care plan was presented, two of the children had not undergone a full psychological assessment and no suitable placements had been found. The care plan did not provide a reasonably clear picture as to the way in which the child’s needs, welfare and well-being would be met: at [66].

See also DFaCS and Boyd [2013] NSWChC 9; Re Tracey (2011) 80 NSWLR 261; Re Rhett [2008] CLN 1.

[40-100] Final care orders

Care orders generally

The orders available to the court in care proceedings, and discussed in further detail below, are the following:

-

orders accepting undertakings (s 73)

-

supervision orders (s 76)

-

orders allocating parental responsibility (s 79)

-

guardianship orders (s 79A)

-

contact orders (s 86)

-

prohibition orders (s 90A)

-

orders for provision of support services (s 74)

-

orders to attend therapeutic treatment (s 75).

It is possible to make consecutive care orders: s 67A.

The fact a particular care order is sought in the care application before the court does not preclude a different or additional order being made, provided all pre-requisites to the making of that order are satisfied: s 67.

Orders accepting undertakings (s 73)

If the court is satisfied a child is in need of care and protection, it may make an order accepting undertakings given by (s 73(1)):

- (a)

a responsible person, with respect to the care and protection of the child, or

- (b)

the child, with respect to their own conduct, or

- (c)

both of the above.

A “responsible person” may be a person with parental responsibility for the child, birth or adoptive parents or primary care-givers (whether or not they have parental or care responsibility): s 73(7).

The undertaking must be signed by the person giving it: s 73(2)(a). The order remains in force for its duration or until the child attains 18 years (whichever is sooner): s 73(2)(b).

The following are examples of undertakings under s 73:

-

the parent is to accept the advice, guidance and support of DCJ officers

-

the parents keep DCJ officers informed of their place of residence and that of the child, and not change such address without first notifying such officers

-

the child be presented by the parents for all medical appointments

-

to comply with the terms of any contact order made by the court with respect to the child,

-

not to consume alcohol 24 hours before contact with the child, and/or not to be under the influence of alcohol or any other substance during contact.

As to breaches of undertakings, see [40-200] Breach of care orders.

Supervision orders (s 76)

If the court is satisfied a child is in need of care and protection, it may make an order placing the child under the supervision of the Secretary: s 76(1).

A supervision order must specify the reason for the order, the purpose of the order and the length of the order: s 76(2).

The maximum period of supervision is 12 months (s 76(3)), however the court may specify a maximum period longer than 12 months, but less than 24 months, if satisfied there are special circumstances warranting an order of that length: s 76(3A). Where a longer period is ordered, the order may be revoked (on the court’s own motion or on the Secretary’s application) after expiration of the first 12 months if the court considers there is no longer a need for supervision in order to protect the child: s 76(7).

The court may also extend, on its own motion or on application by the Secretary, the period of supervision as it considers appropriate, provided the total period does not exceed 24 months: s 76(6).

The court may require a report to be presented before the end of the period of supervision that discusses the outcomes of the supervision, whether the purposes of supervision have been achieved, and whether there is a need for further supervision and/or other orders in order to protect the child: s 76(4)(a). The court can also order one or more progress reports during the supervision period: s 76(4)(b). The court may consider a report after the period of supervision ends, provided it is both reasonable in the circumstances and in the best interests of the child and, after considering such a report, may make a new supervision order for a duration of no more than 24 months from the start of the original supervision order: s 76(4A), (4B).

Orders allocating parental responsibility (s 79)

Parental responsibility means all the duties, powers, responsibilities and authority which, by law, parents have in relation to their children: s 3.

Where the court finds a child is in need of care and protection, it may make an order allocating all, or one or more specific aspects of, parental responsibility for a specified period: s 79(1).

The court cannot make an order unless particular consideration has been given to the permanent placement principles and the court is satisfied the order is in the child’s best interests: s 79(3). The permanent placement principles are to be read subject to the objects of the Act in s 8 and the principles in s 9: LZ v FACS [2017] NSWDC 414 at [236].

Who may be allocated parental responsibility?

Parental responsibility may be allocated to the following person(s) (s 79(1)):

- (a)

to one parent to the exclusion of the other, or to both parents jointly, or

- (b)

solely to the Minister, or

- (c)

to one or both parents and to the Minister jointly, or

- (d)

to one or both parents and to another person or persons jointly, or

- (e)

to the Minister and another suitable person or persons jointly, or

- (f)

to a suitable person or persons jointly.

The court must not allocate parental responsibility jointly between two or more persons unless satisfied they can work together co-operatively in the child’s best interests: s 79(8).

If aspects of parental responsibility are allocated jointly between the Minister and another person(s), either the Minister or the other person may exercise those aspects but if they disagree the disagreement is to be resolved by order of the court: s 79(7).

Aspects of parental responsibility

Section 79(2) sets out, without limitation, specific aspects of parental responsibility which may be allocated:

- (a)

the child’s residence

- (b)

contact

- (c)

education and training

- (d)

religious and cultural upbringing

- (e)

medical and dental treatment.

Special requirements where all aspects are allocated to the Minister

If all aspects of parental responsibility are allocated to the Minister, the maximum period for the order is 24 months, if the permanency plan approved by the court involves restoration, guardianship or adoption (unless the court finds there are special circumstances warranting a longer period): s 79(9)–(10). For care applications made on or after 15 November 2023, in determining whether there are special circumstances warranting the allocation of parental responsibility for more than 24 months, the court is to have regard to the matters set out in s 79AA; Sch 3 Pt 14 cl 2(e).

The Minister must, so far as is reasonably practicable, have regard to the views of the persons who had parental responsibility for the child before the order was made while still recognising that the child’s safety, welfare and well-being remains the paramount consideration: s 79(6).

Restrictions on s 79 orders

Parental responsibility cannot be allocated to an organisation or principal officer of a designated agency (other than the Secretary): s 79(4A).

The court must not make an order under s 79:

-

if, taking into account the permanent placement principles, it would be more appropriate to make a guardianship order under s 79A: s 79(4)

-

if the order would be inconsistent with:

- (a)

-

any Supreme Court order exercising jurisdiction with respect to the custody and guardianship of the child, or

- (b)

-

a guardianship order made by the Guardianship Tribunal: s 79(5).

Suitability reports and progress review

When making an order under s 79 allocating parental responsibility to any person other than a parent, the court may order a party to prepare a written report concerning the suitability of the arrangements for the care and protection of the child: s 82(1).

The report must:

-

be provided to the court within 24 months (or an earlier period if the court specifies), or after that time if it is reasonable in the circumstances and in the best interests of the child, and

-

include an assessment of progress in implementing the care plan, including progress towards the achievement of a permanent placement, and

-

be given to each other party to the proceedings (unless the court orders otherwise): s 82(2).

If the court considers the report and is not satisfied that proper arrangements have been made for care and protection of the child it can, on its own motion, re-list the matter for the purpose of conducting a review of progress in implementing the care plan (a “progress review”): s 82(3).

If the court intends to conduct a progress review, it must give notice of its intention within 30 days of receiving the report: s 82(3A)(a). It may also invite the party to give evidence and make submissions at the progress review, regarding progress in implementing the care plan, including progress towards achieving a permanent placement: s 82(3A)(b).

Allocation of parental responsibility by guardianship order (s 79A)

Guardianship orders are governed by s 79A of the Act. The court may make an order allocating to a suitable person all aspects of parental responsibility for a child who is in statutory or supported out-of-home care, or who it finds is in need of care and protection until the child reaches 18 years of age: s 79A(2).

The court must be satisfied of each of the following (s 79A(3)):

-

there is no realistic possibility of restoration of the child to the parents, and

-

that the prospective guardian will provide a safe, nurturing, stable and secure environment for the child or young person and will continue to do so in the future, and

-

if the child or young person is an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child or young person — permanent placement of the child or young person under the guardianship order is in accordance with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child and Young Person Placement Principles that apply to placement of such a child or young person in statutory out-of-home care under s 13, and

-

if the child or young person is 12 or more years of age and capable of giving consent — the consent of the child or young person is given in the form and manner prescribed by the regulations: cl 12.

Parental responsibility may be allocated jointly to more than one person under a guardianship order: s 79A(4).

A guardianship order cannot be made if it would be inconsistent with any Supreme Court order with respect to the child made under its custody and guardianship of children jurisdiction, or a guardianship order made by the Guardianship Tribunal: s 79A(5).

Unless varied or revoked under s 90, a guardianship order remains in force until the child reaches age 18: s 79A(6).

The court’s power to order suitability reports or to undertake a progress review applies only to orders allocating parental responsibility under s 79, and not to orders allocating parental responsibility by guardianship order under s 79A: s 82(1).

Contact orders (s 86)

Section 86(1) provides that the court may make an order doing any one or more of the following:

- (a)

stipulating minimum requirements concerning the frequency and duration of contact between a child or young person and his or her parents, relatives or other persons of significance to the child or young person,

- (b)

requiring contact with a specified person to be supervised,

- (c)

denying contact with a specified person if contact with that person is not in the best interests of the child or young person.

Contact orders may be made (s 86(1A)):

on application by a party to proceedings before the court with respect to a child, or

on application, with leave, by any person who:

- (i)

was a party to care proceedings with respect to the child,

- (ii)

considers himself or herself to have a sufficient interest in the child’s welfare.

The court may grant leave if it appears there has been a significant change in any relevant circumstances since a final order was made: s 86(1B). Before granting leave, the court must consider whether there has been an attempt to reach an agreement about contact arrangements by participation in alternative dispute resolution, and may order participation in dispute resolution under s 65 or s 65A: s 86(1D).

For assistance in determining the matters to be considered in making a decision regarding contact, regard should be had to the Children’s Court Contact Guidelines.

In identifying the contact arrangements which will properly answer the needs of the individual child, the court is required to consider a number of factors depending on the circumstances of the particular case, and to balance the benefits and risks of contact with the primary focus on the child’s best interests: Re Helen [2004] NSWLC 7.

Section 86 requires the court not only to consider whether any contact, and if so of what nature, should be ordered, but also whether any such contact should be supervised: Re Liam [2005] NSWSC 75 at [42]. The court must obtain the consent of the proposed supervisor before making an order for supervised contact. If the supervisor does not accept the requirement then contact should not be given: s 86(2), (4); Re Liam, above, at [48]; SM v Director-General, Department of Human Services [2010] NSWDC 250 at [11].

- Note:

-

Contact orders do not prevent a person having parental responsibility consenting to contact. In order to prevent a person having parental responsibility giving such consent it is necessary to make an order under s 90A (see, below, Prohibition orders at [40-100]).

As there is no provision in the Act for the enforcement of contact orders, it may be advisable to make an order accepting undertakings to comply with the contact order (see above, Orders accepting undertakings at [40-100]).

Duration of contact orders

A contact order has effect for the period specified in the order, unless varied or rescinded under s 86A or s 90: s 86(5). However, if the court finds there is no realistic possibility of restoration of a child to his or her parent, the maximum period for the order is 12 months: s 86(6).

Contact orders and children the subject of guardianship orders

Supervision must not be ordered in relation to contact with a child who is the subject of a guardianship order: s 86(2).

The 12-month limitation under s 86(6) does not apply to a contact order concerning a child the subject of a guardianship order if the court is satisfied a contact order longer than 12 months (for example, for the duration of the guardianship order) is in the child’s best interests: s 86(8).

Variation of contact orders by agreement

The terms of a contact order may be varied by agreement between the parties. A contact variation agreement must be in writing, signed and dated by the affected parties (and the child’s legal representative, if the variation agreement is made within 12 months of the order), and registered with the court: s 86A(2).

Prohibition orders (s 90A)

At any stage in care proceedings, the court can make an order prohibiting a person (including a parent or any person who is not a party to the care proceedings), in accordance with the terms of the order, from doing anything that could be done by the parent in carrying out his or her parental responsibility: s 90A(1).

The terms of s 90A are wide and permit the court to make a variety of orders. Examples include:

-

an order prohibiting the father from allowing the mother to have unsupervised contact with the child: Re M (No 5) — BM v Director-General, DFaCS [2013] NSWCA 253

-

an order prohibiting the parents from removing the children from the Commonwealth of Australia without the prior written consent of the Secretary: LZ v FACS [2017] NSWDC 414

-

an order prohibiting the mother from having any contact with the children until the children attain the age of 18: FACS v Dimitri [2012] NSWChC 12

-

an order prohibiting the mother from living alone with the child: Secretary, DFaCS and M [2015] NSWChC 1.

As to breaches of undertakings, see below, [40-200] Breach of care orders.

Order for provision of support services (s 74)

Under s 74(1), the court may make an order directing a person or organisation to provide support for a child (other than a child the subject of an application for a guardianship order) for a specified period (not exceeding 12 months).

The preconditions for such an order are set out in s 74(2):

-

the person or organisation who would be required to provide the support has been notified, given an opportunity to appear and be heard by the court, and consents to the making of the order, and

-

the child’s views in relation to the proposed order have been taken into account.

The parents of a child cannot be compelled to accept the provision of support services, particularly if the services relate to the parents rather than to the child, although acceptance can be the subject of an undertaking under s 73.

Order to attend therapeutic treatment (s 75)

The court may require a child (aged less than 14 years) to attend a therapeutic program relating to sexually abusive behaviours, and require the child’s parents to take whatever steps are necessary to enable the child to participate in the program: s 75(1). The order is only available in relation to a child who has exhibited sexually abusive behaviour: s 75(1A).

The court may also order a parent to attend either:

-

a therapeutic program relating to sexually abusive behaviours, or

-

any other kind of therapeutic or treatment program: s 75(1B).

The court must be presented with, and consider, a treatment plan outlining the proposed treatment before an order can be made: s 75(3).

Orders are not available under this provision if the child (or parent) has been convicted in criminal proceedings arising from the same sexually abusive behaviours: s 75(2).

Orders under this provision are not available in relation to applications for a guardianship orders: s 75(4).

[40-120] Costs in care proceedings

The court cannot make an order for costs in care proceedings unless there are exceptional circumstances that justify it in doing so: s 88.

Examples of cases in which exceptional circumstances have been found to justify an order for costs include:

-

Re: A foster carer v DFaCS (No 2) [2018] NSWDC 71 (FACS knowingly relied on inadequate investigations)

-

Secretary, DFaCS v Tanner [2017] NSWChC 1 (Secretary’s Care Plan was “deliberately misleading” and “baseless”)

-

Secretary, DFaCS and the Knoll Children [2015] NSWChC 2 (Department’s handling of matter required carers to obtain separate legal representation)

-

Director General, DFaCS v Robinson-Peters [2012] NSWChC 3 (Mother ordered to pay father’s costs due to gross incompetence of legal representation)

-

Department of Community Services v SM (2008) 6 DCLR (NSW) 384 (Department’s appeal without grounds or merit)

The situations in which exceptional circumstances may be found are not exhaustively defined or limited by prior cases; the court may have regard to the particular circumstances of the case, including evidence adduced, conduct of the parties and the ultimate results: Secretary, DFaCS and the Knoll Children, above, at [26].

Section 88 does not provide the court with power to award costs against a non-party such as a legal representative: Director General, DFaCS v Robinson-Peters, above, at [54].

[40-140] Alternatives to care applications — registration/approval of a care plan (s 38)

A care plan developed by agreement during alternative dispute resolution may be registered with the court: s 38(1). A care plan is taken to be registered with the court when it is filed with the registry, without any order or other action by the court: s 38F.

A registered care plan allocating parental responsibility, or aspects of parental responsibility, to any person other than the child’s parents only takes effect if the court makes an order by consent to give effect to the proposed changes: s 38(2). No care application needs to be made, and the court does not need to be satisfied of any ground under s 71 that the child is in need of care and protection: s 38(2A).

However, the court is required to be satisfied that:

-

the proposed order will not contravene the principles of the Act, and

-

the parties to the care plan understand its provisions and have freely entered into it, and

-

any party other than the Secretary has received independent legal advice concerning the provisions to which the proposed order will give effect, and of the nature and effect of the proposed order: s 38(2B).

The court may also make such other care orders as it could make under Ch 5, Pt 2 of the Act to give effect to the care plan (for example, an order accepting undertakings), if satisfied of the same matters as required by s 38(2B): s 38(3).

Section 79B(1A), (8)(b)–(c) applies to the Secretary in seeking a guardianship order by consent to give effect to a care plan under s 38 in the same way as they apply to an application for a guardianship order: s 38(4). Further, the information required under s 79B(9)–(10) must also be included in a care plan developed by agreement which seeks guardianship orders: s 38(5). See above, Allocation of parental responsibility by guardianship order s 79A at [40-100].

[40-160] Applications for rescission or variations of care orders

Application to rescind or vary final orders — leave of the court required

Applications for rescission or variation of final care orders may be made with the leave of the court: s 90(1). Applications for leave may be made by the following (s 90(1AA)):

-

the Secretary

-

the child

-

a person with parental responsibility for the child

-

a person from whom parental responsibility for the child was removed

-

any person who considers him or herself to have a sufficient interest in the child’s welfare.

The court may only grant leave if it “appears that there has been a significant change in any relevant circumstances since the care order was made or last varied”: s 90(2).

The range of “relevant circumstances” will depend upon the issues presented, but may not necessarily be limited to just a “snapshot” of events occurring between the time of the original order and the date the leave application is heard: In the matter of Campbell [2011] NSWSC 761 at [42].

The issue of “significant change” requires that the change appear to be of sufficient significance to justify the court’s consideration of a rescission or variation application: S v Department of Community Services [2002] NSWCA 151 at [23]. A comparison is required between the situation at the time the application is heard and the facts underlying the decision when the order was made or last varied: S v Department of Community Services at [27]. A non-exhaustive list of factors which indicate a significant change are listed in cl 4 Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Regulation 2022.

The discretion available to the court in determining whether to grant leave under s 90(1) is very wide; even if a parent has established a significant change in a relevant circumstance since the care order was made or last varied, the court is not compelled to grant leave. Further, even if the parent has addressed all the issues of concern which led to removal of the child, the length of time the child has been in a stable placement, the age of the child and the expressed wishes of the child that their placement not be disturbed may together strongly support a finding that it is not in the best interests of the child to disturb their current placement: Kestle v Director, DFaCS [2012] NSWChC 2 at [51].

Section 90 prescribes mandatory matters for the court’s consideration when determining whether to grant leave: s 90(2A).

The list of considerations to be considered by the court is split into two categories as follows:

| Primary considerations — s 90(2B) | Additional considerations — s 90(2C) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The court may dismiss applications if satisfied they are frivolous, vexatious or an abuse of process, or if satisfied the application has no reasonable prospect of success and the applicant has previously made a series of unsuccessful applications for leave: s 90(2D), (2E).

The court may restrict the grant of leave to a particular issue or issues: Kestle v Director, DFaCS, above, at [53]; Re M (No 6) [2016] NSWSC 170 at [66]. An example of when a restricted grant of leave may be appropriate is where the court determines that an applicant parent does not have an arguable case for restoration of the child to their care, but does have an arguable case on the issue of increased parental contact: Kestle at [53].

Refusal of leave under s 90(1) is an order of the court: S v Department of Community Services at [48].

Variation of interim orders

The law in relation to variation of interim orders was previously unclear: see Re Mary [2014] NSWChC 7 at [23]–[33]; Re Timothy [2010] NSWSC 524 at [59]–[60].

The Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Amendment Act 2018 (commenced 4 February 2019) inserted s 90AA to provide that a party to care proceedings may apply to the court to vary an interim care order. The court may vary an interim care order if satisfied that it is appropriate to do so: s 90AA(2).

Section 90(9) now expressly provides that s 90 does not apply to an application to vary an interim care order.

Section 90AA extends to proceedings before the court that were pending (but not finally determined) immediately before 4 February 2019.

[40-180] Parent capacity orders