People from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

NSW has a culturally diverse population, born in more than 300 countries, having more than 310 ancestries, communicating in more than 280 languages at home and around 139 different religious beliefs.1 The purpose of this chapter is to:

-

highlight for judicial officers relevant information about the different values, cultures, lifestyles, socioeconomic disadvantage and/or potential barriers in relation to full and equitable participation in court proceedings for people from culturally diverse backgrounds in NSW; and

-

provide guidance about how judicial officers may take account of this information in court — from the start to the conclusion of court proceedings. This guidance is not intended to be prescriptive.

3.1 Introduction2

-

Population — The NSW population according to the 2021 census was 8.07 million residents, up from 7.48 million residents in the 2016 census.

-

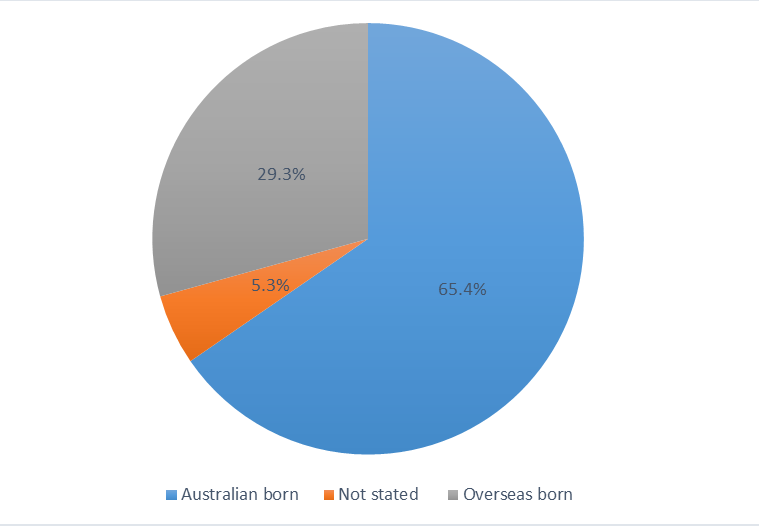

Figure 3.1 shows the breakdown of Australian born and overseas born NSW residents using figures from the 2021 census:

Figure 1.

-

Of the 2.37 million of those born overseas, 1.85 million (or around 78%) were born in an other than main English-speaking country (OTMESC) — that is, a country other than that classified by the ABS as a main English-speaking country (MESC: New Zealand, United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, South Africa, United States of America and Canada).3

-

Approximately 22% of those born overseas were born in a MESC (520,665) — predominantly in the UK, South Africa and New Zealand. Many MESCs have values, customs, laws and legal systems that are similar (although not identical) to those in Australia.

-

Around 30% of those born in an OTMESC were born in China, India and the Philippines. Table 3.1 ranks OTMESC birthplaces according to the percentage of the NSW population born there:

Table 3.1 — NSW residents born in OTMESC: 2021 census figuresBirthplace Number of NSW residents % of NSW population China (excluding SARs and Taiwan) 247,595 3.1 India 208,962 2.6 Philippines 106,930 1.3 Vietnam 97,995 1.2 Nepal 64,946 0.8 Lebanon 63,293 0.8 Iraq 55,353 0.7 South Korea 51,816 0.7 -

The overseas birthplace countries listed above showing the greatest increase between 2016 and 2021 are India, Nepal, Iraq and the Philippines.

-

-

Language spoken:

-

26.6% (2.15 million) of NSW residents speak a language other than English at home.

-

After English, the most common languages spoken at home are Mandarin (3.4%), Arabic (2.8%), Cantonese (1.8%), Vietnamese (1.5%) and Hindi (1%).

-

Around 16.9% of those who speak a language other than English at home speak English “not well” or “not at all”4 (note that this figure differs according to age, with much higher rates of limited English among the older population). Those most likely to be in this situation are migrants from South East Asian countries such as China and Vietnam. However, it should be noted that even those who do speak English reasonably well may need an interpreter in a court situation. For more on this see 3.3.1 below.

-

-

Place of residence — Sydney is recognised internationally as one of the most culturally and ethnically diverse cities in the world. The majority of people born in OTMESCs live in specific areas of Sydney, as do those with varying or lower levels of English proficiencies, that is, those who speak English “not well” or “not at all” (1.7 million). In 2021, almost half (47.9%) of the Sydney Inner City population (218,000) was born overseas, from 183 different countries. The areas of NSW with the highest proportion of their population born overseas were Auburn (61.7% – the highest proportion in Australia), Fairfield (56.1%), Parramatta (54.9%), Strathfield-Burwood-Ashfield (50.2%) and Canterbury (49.4%).5In general, a much smaller percentage of the local population outside Sydney was born in an OTMESC compared with Sydney, and the same can be said for those who speak English “not well” or “not at all”.

-

In NSW during 2019–2020, the areas with the highest net gains through regional overseas migration were both in Sydney — the Inner South West (8,100) and Parramatta (8,000).6 Immigration was impacted due to COVID-19 during 2020–2022 due to Australian border closures.

-

Ancestry or ethnic background:

-

65.4% (5.28 million) of NSW residents are Australian born. Of all NSW residents (those born in Australia and overseas):

-

43.7% (3.53 million) have both parents born in Australia

-

6.3% (509,789) have their father born overseas

-

4.6% (369,492) have their mother born overseas

-

37% (3.18 million) have both parents born overseas

-

6% (481,824) not stated,

-

-

-

Religion — In 2021, of the 12.1% of people in NSW who were affiliated with a non-Christian religion, the most common were Islam (4.3%), Hinduism (3.4%) and Buddhism (2.8%).7It must be noted that the religious affiliations of all people are various and do not necessarily match the dominant religion of their birth country or country of ancestry. For more information about religious affiliation — see Section 4.

-

Socio-economic status:

-

People from culturally diverse communities are more likely than people who were born in Australia and grew up speaking English at home to experience socio-economic disadvantage. General poverty rates are higher among migrants from OTMESCs. In 2019–2020, while 11% (or 1,454,000) of people born in Australia were living in poverty, as well as 11% (or 218,000) of people born in a MESC, there was a poverty rate of 18% (or 887,000 people) among those from OTMESCs.8

-

The unemployment rate for people born overseas is slightly higher than the rate for people born in Australia. However, the gap between the Australian-born unemployment rate and the migrant unemployment rate reduces when the general unemployment rate goes down. In Australia, in 2021, the unemployment rate was 5.2% for Australian born people compared with 5.3% for those born overseas.9 However, this is an aggregated statistic.

-

Newly arrived migrants and those from OTMESCs have higher unemployment rates than those who have been in Australia longer10 and those who come from MESCs — in August 2021, the unemployment rate for migrants from OTMESCs (7.9%) was significantly higher than for those from MESCs (4.2%).11 In the twelve months to February 2023, particularly high unemployment rates were seen from people born in North Africa and the Middle East (7.5%), which the Australian labour market for migrants publication suggests could reflect English language proficiency and period of residence in Australia.12 Additionally, in February 2018 only 39% of adults who had migrated from the Middle East or North Africa were employed 5–10 years after arriving in Australia, compared to 83% of migrants from North-West Europe.13

-

Young migrants from OTMESCs recorded lower labour force participation rates than other cohorts — 59.2%, compared to 70.9% for MESC migrants and 68.5% for youth born in Australia.14

-

Interestingly, the gap between the Australian born unemployment rate and the migrant unemployment rate widens the higher the educational qualification of the migrant — presumably to do with the difficulty of getting overseas qualifications recognised and race discrimination within recruitment and selection practices. However, in 2019 data, recent migrants who had obtained a non-school qualification before arrival had a higher employment rate than those who had not (82% vs 59% for those who did not).15

-

Migrants, and particularly those from culturally diverse backgrounds, often take at least one generation to establish themselves at the same professional level as where they came from due to a combination of the delays caused by migrating and resettling, their varied or lower levels of English proficiency, difficulties negotiating a different culture, the difficulty in getting their overseas qualifications recognised, and some race discrimination in recruitment and selection processes.

-

-

Stigma and assumptions relating to crime rates — within some sections of the community there is a perception (sometimes fed by the media) that members of particular culturally diverse groups are more likely to resort to crime than other cohorts. However, research indicates that statistics about ethnicity and crime rarely take into account social and economic variables. In other words, social disadvantage would appear to be the main influencing factor in relation to propensity to crime, not ethnicity.16

Australian Bureau of Statistics figures17 reveal that of the NSW prison population in 2022 of 12,372 inmates, 9527 were Australian born (7.7%) and of the overseas born groups listed, those born in New Zealand, Vietnam, Lebanon, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, Iran and Sudan are over-represented in the prison population. As stated above, there is likely a correlation between the levels of imprisonment in these groups and general socio-economic disadvantage (with the possible exception of New Zealand), similar to that in Australia’s First Nations population — see 2.1, 2.2.2.

3.2 Cultural diversity

3.2.1 Cultural differences

-

It is now well-accepted among medical scientists, anthropologists and other students of humanity that “race” and “ethnicity” are social, cultural and political constructs, rather than matters of scientific “fact”.18

-

Each culturally diverse group will have its own set of cultural customs.

-

Each culturally diverse group also contains its own set of variances and sub-cultures — for example, there is not just one Vietnamese or Lebanese cultural “norm”. Multicultural communities are steeped in diversity, not limited to language, faith, cultural values and geography. The assumption that a single individual or organisation represents their entire community can risk isolating members of the community.

-

Each culturally diverse group has also generally deviated from at least some of the cultural customs that are common in their country of ancestry — due to the impact of the (for many, extremely difficult) migration and settlement experience and then acculturation to living in Australia.

-

It is also important to note that not all members of particular culturally diverse groups follow the cultural customs for their group, or they may alter their behaviour (particularly in public) to better align with Western cultural customs. For example, some individuals from culturally diverse backgrounds feel the need to engage in “code-switching” — that is, adapting their behaviour, speech, appearance, name or expression to better reflect the dominant white culture — to decrease the risk of discrimination and exclusion, particularly in a professional environment.19

-

However, there are some common cultural differences between people from many culturally diverse backgrounds and people accustomed to Western cultural customs that may influence:

-

The way in which people from different culturally diverse backgrounds present themselves and behave in court.

-

The way in which they perceive justice to have been done or not done.

-

The way in which justice actually is or is not done. For example, justice may not have been done if false assumptions have been made about a person from a culturally diverse background based on how a person accustomed to Western cultural customs would behave.

-

3.2.2 Examples of common cultural differences

Some of the common cultural differences between people from culturally diverse groups and people accustomed to Western cultural customs can be grouped as follows:

-

Different naming systems and modes of address — see 3.3.2.1 below.

-

Differences in family make-up and in how individual members of the family are perceived and treated — see 3.3.6.2 below.

-

Different styles of behaviour and appearance, and allied with this, different customs about how men and women and sometimes children should behave and be treated, and/or different customs about how people in authority should behave and be treated, and/or different customs about such things as marriage, property ownership and inheritance — see 3.3.4.2 and 3.3.6.2 below.

-

Different communication styles (linguistic and body language), combined in many cases with varied or lower levels of (Australian) English proficiency.

- Note:

-

also that an individual’s ability to communicate in English is often reduced in situations of stress — such as court appearances.

-

Different understanding and experiences of how legal and court systems work and what they are capable of, and sometimes a much lesser understanding of the Australian legal and court system than those accustomed to Western cultural customs. Many culturally diverse people come from countries that use completely different systems — for example, an inquisitorial system or have experienced an extremely repressive dictatorial or corrupt and in their view unjust system. They may not have had any knowledge about the Australian jury system, cross-examination, what can and cannot be said in evidence, the importance of intent, and what bail represents and means. They may have very good reasons to fear everything to do with the legal and court system and particular reason to fear the type of questioning that can occur under strenuous cross-examination. They may be survivors of torture and trauma, which would make the court experience particularly terrifying.

-

Different customs between the generations — those from younger generations may be more likely to adhere to (or want to adhere to) Western cultural customs than those from older generations — see 3.3.6.1 below.

-

People from culturally diverse backgrounds may have experienced racism and race discrimination in Australia. Experiences of racism were widespread during COVID-19with racist verbal attacks, physical abuse and derogatory and xenophobic slurs being experienced “as though they were personally infected by COVID-19 by virtue of their foreign appearance.”20

3.2.3 The possible impact of these cultural differences in court

The adversarial nature of the Australian court system means it can be uncomfortable and difficult to navigate for any individual, regardless of their cultural background or dominant language. However, unless appropriate account is taken of the types of cultural differences listed in 3.2.2 above, people from culturally diverse backgrounds may be particularly likely to:

-

Feel uncomfortable, fearful or overwhelmed.

-

Feel offended by what occurs in court.

-

Not understand what is happening or be able to get their point of view across and be adequately understood.

-

Feel that an injustice has occurred.

-

In some cases, be treated unfairly and/or unjustly.

- Note:

-

that s 13A Court Security Act 2005 provides that court security staff may require a person to remove face coverings for the purposes of identification unless the person has “special justification” (s 13A(4)) which includes a legitimate medical reason. Face coverings are defined as an item of clothing, helmet, mask or any other thing that prevents a person’s face from being seen.21 The court security officer must ensure the person’s privacy when viewing the person’s face if the person has asked for privacy.22

Section 3.3, following, provides additional information and practical guidance about ways of treating people from different ethnic and/or non-English speaking backgrounds during the court process, so as to reduce the likelihood of these problems occurring.

3.3 Practical and legal considerations23

3.3.1 The need for an interpreter or translator

3.3.1.1 Assessing when to use the services of an interpreter or translator

An interpreter is someone who “transfers a spoken or signed message from one language (the source language) into a spoken or signed message in another language (the target language) for the purpose of communication between people who do not share the same language”.24

A translator is someone who transfers “a written message from one language (the source language) into a written message in another language (the target language) for the purpose of communication between a writer and reader who do not share the same language”.25

Interpreters are required to act with accuracy and impartiality,26 and are subject to the Code of conduct for interpreters in legal proceedings.27 The Australian Institute of Interpreters and Translators (AUSIT) Code of ethics and code of conduct28 and Australian Sign Language Interpreters’ Association (ASLIA) Code of ethics29 also apply to relevant language service professionals.

In many cases, an appropriately credentialed interpreter or the appropriate level of translation will already have been arranged by the time the person appears in court or the document is used in court — by the solicitor or barrister who is acting on behalf of or calling the particular person to court, or who is using the particular document.

However, there will be times when this has not happened, and the court will need to assess the need for an interpreter or translator. The Judicial Council on Diversity and Inclusion (JCDI) (previously the Judicial Council on Cultural Diversity) produced a resource in 2017 Recommended national standards for working with interpreters in courts and Tribunals (Recommended national standards). A second edition was published in March 2022. The resource recommends that if a party or witness in court has difficulties understanding or communicating in English at any point, or if the person asks for an interpreter, the judicial officer should stop proceedings and arrange for an interpreter to be present. The Recommended national standards suggest that the judicial officer apply a four-part test to assess the need for an interpreter outlined in Annexure 4 of the resource.30

In November 2019 the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 2005 (NSW) Pt 31 Div 3, which is based on the Model Rules set out in the Recommended national standards, was enacted.

Legal principles

While there is no specific “right” to an interpreter, procedural fairness requires that the language needs of court users be accommodated. Various statutory provisions allow for the use of an interpreter, for example, s 30 of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW):

A witness may give evidence about a fact through an interpreter unless the witness can understand and speak the English language sufficiently to enable the witness to understand, and to make an adequate reply to, questions that may be put about the fact.

In relation to ex tempore reasons, see Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs v AAM17 (2021) 272 CLR 329, where the High Court accepted that as a matter of general fairness, rather than independent legal duty, the first respondent ought to have had the benefit of translated ex tempore reasons or written reasons at an earlier time: at [22]. However, the first respondent was not deprived of the opportunity to formulate his argument on appeal because of the fact the primary judge’s ex tempore reasons were not translated, nor was he denied the opportunity to investigate any difference in substance between those reasons and the published reasons: at [43]. See also Murray v Feast [2023] WASC 273, where it was found that the magistrate erred in not allowing an interpreter where the defendant spoke Aboriginal English and Kriol. The Court was in substance expressing, in Mr Murray’s presence, an erroneous view about the genuineness of Mr Murray’s need for interpretation and therefore an erroneous view about the honesty of Mr Murray’s approach to the giving of evidence generally: at [175].

NSW Government agencies will fund the provision of language services (that is, interpreters and translated materials) when dealing with clients, in order to provide all clients with access to Government services.

Under Article 14(3) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, a person facing criminal charges has the right to the free assistance of an interpreter if he or she “cannot understand the language of the court”. Australia has signed and ratified this convention.

An accused in a criminal trial in NSW has a right not to be tried unfairly, usually expressed as a right to a fair trial. There are many decisions where the provision of an interpreter has been discussed and then stressed as being critical wherever there is any possibility that to not provide one would disadvantage a party or their right to a fair trial. In the High Court’s decision in Re East; ex p Ngyuyen Kirby J said that:

where a trial would be unfair because of the absence of an interpreter, it is the duty of the judicial officer to endeavour to ensure that an interpreter is provided.31

The JCDI Recommended national standards for working with interpreters in courts and tribunals summarises the statutory and common law sources of the “right” to an interpreter in civil and criminal proceedings.32

3.3.1.2 Recommended national standards for working with interpreters in courts and tribunals

The JCDI’s Recommended national standards for working with interpreters in courts and tribunals35 were produced to establish recommended and optimal practices for working with interpreters, with the aim of improving access to justice and procedural fairness. This resource has been recommended by the Council of Chief Justices. The Recommended national standards centre on steps than can be taken from an institutional perspective, to ensure better working with interpreters, including:

-

provision of information to the public about the availability of interpreters

-

facilitation of training for judicial officers and court staff on the Recommended national standards and working with interpreters

-

assessing the need for an interpreter

-

coordination and engagement of interpreters by the court

-

court budget for interpreters

-

appropriate support for interpreters

-

provision of professional development to interpreters on the Recommended national standards; and

-

adoption of the Model Rules to give effect to the proposed standards.

Practice Note SC Gen 21 — Interpreters in Civil Proceedings commenced operation on 4 March 2020 and applies to all civil proceedings commenced after its commencement and to any existing proceedings which the court directs should be subject to the Practice Note, in whole or in part. The Practice Note states that the court has resolved to implement and apply the Recommended national standards, which must be read together with Uniform Civil Procedure Rules Pt 31 Div 3. The Practice Note covers when parties are assessing the need for an interpreter, matters to be considered when an interpreter is engaged, conduct of proceedings, and interpreter fees.

In 2022 the JCDI published a companion document to the Recommended national standards entitled Interpreters in criminal proceedings: benchbook for judicial officers,36 to assist judicial officers who are required to work with interpreters in criminal proceedings.

3.3.1.3 Level of interpreter or translator to employ

In general, only interpreters and translators certified by the National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters (NAATI) and only those certified at the appropriate level for the particular type of interpreting and/or translation necessary should be engaged.37 Preferably, practitioners who are also formally trained should be given preference over those who are only certified. Not all practitioners are certified and/or trained at the appropriate level for both interpreting and translation. Using the services of a non-certified practitioner can hinder communication in court and lead to a successful appeal and/or retrial if the trial is found to be unfair. The NSW Court of Criminal Appeal ordered a new trial in R v Saraya38 because “the deficiencies in interpretation were such that the appellant was unable to give an effective account of the facts vital to his defence”.

- Note:

-

that NAATI does not test for all new and emerging languages and has no specification of level of proficiency for these. However, NAATI does issue a Recognised Practising Interpreter (or Translator) credential in these circumstances. Anyone holding a Recognised Practising credential has had to demonstrate social and ethical competency as well as work experience and is still subject to continuing professional development and professional conduct obligations.39

There are several techniques of interpreting:40

-

Consecutive interpreting is when the interpreter listens to larger segments, taking notes while listening, and then interprets while the speaker pauses.

-

Simultaneous interpreting is interpreting while listening to the source language, ie, speaking while listening to the ongoing statement. Thus the interpretation lags a few seconds behind the speaker … In settings such as business negotiations and court cases, whispered simultaneous interpreting or chuchotage is practised to keep one party informed of the proceedings.

Note that both consecutive and simultaneous interpreting fall within the umbrella of “dialogue interpreting”, which involves a conversation between two or more people, mediated by an interpreter.

-

Sign language interpreting — see the ASLIA guidelines for interpreters in legal settings.41

-

Sight translation involves transferring the meaning of the written text by oral delivery (reading in one language, relaying the message orally in another language). An interpreter may be asked to provide sight translation of short documents.

.

Note: that besides face-to-face interpreting there are other channels of interpretation including via telephone or video conference, which should be used where appropriate and available.42

NAATI’s new certification system (which came into effect in 2019) has been designed to evaluate that a candidate demonstrates the skills needed to practise as a translator or interpreter in Australia.43 Certified specialist legal interpreters (CSLI) are experienced and accomplished interpreters who are experts in interpreting in the legal domain. They have completed training and undertake continuous professional development in specialist legal interpreting. Note that in some emerging communities, the only interpreters available may be certified provisional interpreters: their use should be monitored very carefully. See the Recommended national standards for the order of preference for an interpreter’s level of qualification and certification to be followed when engaging an interpreter in a court setting, and the extent to which the level of qualification of an interpreter is often subject to availability of interpreters in the language required.44

In many courts, due to the significant numbers of people who use specific languages, courts have arranged to have interpreters from common languages at the courthouse all day to assist anyone. For example, Liverpool Local Court has an Arabic interpreter at the courthouse every Tuesday. Use of these lists greatly assists with the efficiency of the court and promotes equitable access to the justice system.

The suppliers of interpreters and translators (see 3.3.1.4 below) can advise which level would be the most appropriate for a particular situation.

Most NAATI certified translators and interpreters belong to a professional body — the Australian Institute of Interpreters and Translators Incorporated (AUSIT). Members have to abide by AUSIT’s Code of Ethics based on eight principles: professional conduct, confidentiality, competence, impartiality, accuracy, employment, professional development and professional solidarity.45

It will greatly assist interpreters of any level to perform at a higher standard if they are briefed prior to any assignment. This may include a summary of the case in which they will be required to interpret, if possible, or at the very least, some information from the judicial officer at the commencement of their interpreting job. Interpreters should also be made aware that they are allowed to ask questions to seek clarification if needed in order for them to render accurate interpretations.46

It may also be important to consider — given the subject matter, any cultural considerations and the need to get the best possible evidence with as little difficulty as possible — whether to specifically ask for a male or female interpreter (for example in matters where the person may feel culturally uncomfortable having someone of the opposite sex interpret for them — such as matters relating to sexual activity, sexual assault or domestic violence), and/or consider both the backgrounds of the individuals who require interpretative services and of the interpreter, and whether it is advisable to do so (in order to minimise cultural discomfort and any concerns about possible misinterpretation) — for example, a Serbian Serbo-Croatian speaker as opposed to a Croatian Serbo-Croatian speaker.

And it is important to work out precisely what language, or in some cases dialect of a particular language, the interpreter needs to speak. This means care may need to be taken to establish in what country or region they learned their particular language — for example, do they speak European, Brazilian or African Portuguese?

See further UNSW’s project “Access to justice in interpreted proceedings: the role of Judicial Officers”.47

This project is using an innovative interdisciplinary approach and aims to generate new knowledge in examining the variations in judicial officers’ communications practice when working with interpreters, and their impact on the effective transmission of information in the courtroom. Expected outcomes of this project will include improved outcomes of interpreted communication and better access to justice for participants with limited English proficiency.

3.3.1.4 Suppliers of interpreters and translators

There are two main suppliers of NAATI-certified interpreters and translators in NSW:

-

Multicultural NSW — .face-to-face interpreting services are provided 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for over 120 languages and dialects (excluding Auslan) — Ph 8255 6767, or a quote can be requested online through the booking system.48 Over the financial year to 30 June 2022, Multicultural NSW provided over 22,000 interpreting services in Local Courts across NSW covering 113 languages — Arabic, Mandarin, Vietnamese, Cantonese and Persian being the most requested.49

Note: that Multicultural NSW has a contract with courts to provide interpreters in criminal matters, domestic violence and sexual assault cases free of charge.

-

The Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) run by the Commonwealth Department of Home Affairs — provides telephone interpreting services 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, on-site interpreters and a document translation service for over 150 languages and dialects — Ph 131 450.

There are also independent interpreters or translators. If any of these are engaged, you need to check that they hold appropriate NAATI certification — see 3.3.1.2.

3.3.1.5 Who pays for an interpreter or translator

It is important that individuals are made aware of who pays for language services before proceedings have begun in order to prevent confusion and provide greater clarity for all who come before the court.

If an interpreter is required in a criminal or apprehended violence matter, court staff can arrange this: the service is free. The court registry must be advised that an interpreter is required as soon as court attendance dates are known. Multicultural NSW will provide an interpreter free of charge — under their contract with courts.

In civil cases each party is generally responsible for paying for any interpreters or translators they require for themselves or their witnesses, however, at the end of the trial the successful party may ask to recover any interpreter/translator costs as part of their costs submission. If the court considers the costs would create a hardship, it may order that an interpreter be provided for the hearing. Interpreter costs have become a particular issue in cases where the parties have been ordered to participate in an ADR conference. Having limited English proficiency significantly disadvantages a person’s ability to participate in the ADR.

3.3.1.6 The provision of certified interpreters and certified translations before court proceedings start

It is important to check (at the relevant point in the proceedings), whether, in the lead up to the court proceedings, all relevant parties have had any necessary access to interpreters and/or translated documents such as statements and affidavits, that it is critical for them to have understood before signing, or to have been able to read in advance and/or adequately understand.

3.3.1.7 Working with an interpreter — guidelines for magistrates and judges50

3.3.2 Modes of address

3.3.2.1 Different naming systems

Some culturally diverse groups have different naming systems from the generally gender-specific “first” or “given” name, then middle name, then family name system used by individuals accustomed to Western cultural customs.

For example, they may:58

-

Reverse the order of names and thus start with their family name and end with their given name — for example, Chinese and Vietnamese.

-

Not have a family name at all.

-

Not often use their family name when referring to someone else — using their given name and middle name only.

-

Have particular words in their names, or prefixes or suffixes attached to one of their names that indicate such things as:

-

Gender — for example, in general the Vietnamese middle names of “Van” for men and “Thi” for women.

-

Marital status.

-

Son of, or daughter of — for example the Muslim prefix “ibn” meaning “son of”, ”binte” meaning daughter of.

-

Father of, or mother of — for example the Muslim “Abu” meaning “father of “ and “Umm” meaning mother of.

-

Using both their paternal and maternal surnames.

-

However, not all members of a group will follow the common cultural customs of their group. And many have either completely adopted Western naming system, or use alternative names that fit the Western naming system when they deal with Australian bureaucracy.

Some non-English names may be difficult for English speaking monolingual Australians to pronounce. Or the original language may be tonal. In tonal languages each word has a marker that indicates whether the tone of each word should be rising, falling, even, etc and therefore how it should be pronounced. Unfortunately, there is no easy way of indicating this in English.

3.3.2.2 The mode of address and/or naming system to use

People from some culturally diverse backgrounds may expect and prefer to be addressed very formally when in a formal situation such as a court, or when addressed by someone younger than themselves, or when addressed by someone of the opposite gender – for example, they may prefer to be addressed as Mr/Ms/Mrs given name, or Mr/Ms/Mrs family name. Others may prefer to be addressed by their given name only. Others may only know each other by a nickname that bears little resemblance to the person’s actual name, and be happy for you to use the same nickname.

3.3.3 Oaths and affirmations

See Section 4.4.2 for information on oaths and affirmations, as any differences that may be required in relation to oaths and affirmations will be largely dependent on a person’s religious affiliation or lack of religious affiliation, rather than their cultural background.

- Note:

-

however, that s 34 of the Oaths Act 1900 provides that a person witnessing a statutory declaration or affidavit must see the face of the person making the declaration or affidavit to identify the person. Therefore, the witness may request a person who is seeking to make a statutory declaration or affidavit to remove so much of any face covering worn by the person as prevents the authorised witness from seeing the person’s face. A “face covering” is defined as an item of clothing, helmet, mask or any other thing worn by a person that prevents their face from being seen.60

3.3.4 Appearance, behaviour and body language

3.3.4.1 Background information

-

It is commonly known that most people, including jurors, are likely to, at least in part, assess a person’s credibility or trustworthiness on their demeanour.

-

Yet, not only has demeanour been found to be an unreliable indicator of veracity,61 but also our appearance, behaviour and body language are all heavily culturally determined.

-

This means that it is vital that no-one in the court allows any culturally determined assumptions about what they believe looks trustworthy and what does not to unfairly mislead or influence their assessment of the credibility or trustworthiness of a person from a culturally diverse background.

-

For some people from culturally diverse backgrounds, the traits that individuals accustomed to Western cultural customs may regard as indicative of dishonesty or evasiveness (for example, not looking in the eye) are the very traits that are the cultural “norm” and/or expected to be displayed in order to be seen as polite and appropriate and not be seen as rude or culturally inappropriate.

-

Just as there are sub-cultures within Western culture that observe different styles of appearance, behaviour and body language, and also individuals who do not follow any particular cultural custom, there are similar examples within any other culture. So, it is also important not to assume that everyone born in a particular country will behave in the same way, or to assess people from the same cultural background who do not seem to follow the typical patterns of behaviour of that culture as dishonest or lacking in credibility.

3.3.4.2 Examples of differences and the ways in which they may need to take into account

3.3.5 Verbal communication

3.3.5.1 Background information

People from culturally diverse backgrounds and particularly those with limited English proficiency may face a number of difficulties in relation to aspects of verbal communication in court proceedings.

For example, as indicated earlier in this Section, they may have:

-

Difficulties understanding (Australian) English.

-

A different communication style that makes it hard for others to adequately understand them, or means that they are wrongly assessed as, for example, evasive or dishonest.

-

A different understanding of how legal and court systems work and what they are capable of, and little or no understanding of the Australian legal and court system. Many come from countries using completely different systems — for example, an inquisitorial system or have experienced an extremely repressive dictatorial or corrupt and in their view unjust system. They may not have any understanding of the jury system, cross-examination, what can and cannot be said in evidence, the importance of intent, what bail represents and means, etc. They may well have very good reasons to fear everything to do with the legal and court system and particular reason to fear the type of questioning that can occur under strenuous cross-examination. They may be survivors of torture and trauma thus making the court experience particularly terrifying.

It is critical that these matters are taken into account so as not to unfairly disadvantage the particular person. Just like everyone else, a person from a culturally diverse background who appears in court needs to understand what is going on, be able to present their evidence in such a manner that it is adequately understood by everyone who needs to be able to assess it, and then have that evidence assessed in a fair and non-discriminatory manner.

3.3.5.2 Avoid stereotyping and/or culturally offensive language

3.3.5.3 Take appropriate measures to accommodate those with limited English proficiency, or with different styles of communication

- Note:

-

that an individual’s ability to communicate in English is often reduced in situations of stress — such as court appearances. Further, some people may be more able to understand English than to speak it, or more able to speak it than understand it. Someone who appears to speak perfect English may still find the language used in court or by lawyers very difficult to follow.

People from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds may:

-

Use a much more roundabout style, for example, gradually building a picture before finally getting to the point that an individual who grew up speaking English at home would have started with.

-

Talk much more slowly, or much more quickly.

-

Use much less powerful sounding speech — that is, with many more hesitations, silences, hedges (“I think”, “it seems like”, “sort of”, “actually”) and/or terms of politeness (sir, madam, please). Native English speakers tend to do this when they are from less powerful sub-groups or have a lesser level of formal education. People from culturally diverse backgrounds may do this even if they are from relatively powerful sub-groups within their culture and/or are highly educated. See also 3.3.4.2 above, in relation to silence and/ or apparent avoidance in answering the question.

-

Talk more quietly or more submissively. This is often more pronounced in women than men, although men may also do it.

-

Prefer to agree with whatever is being put to them, or to come up with some form of compromise, rather than to openly disagree with whatever is being put to them — even when they do disagree. For example, in some cultures it is “considered impolite to flatly disagree with a questioner”.65 Some people who do this may try to indicate that they would prefer to come back to that subject later, others may not.

-

Use more, fewer or different hand gestures and body movements, and/or find the gestures and body movements used by individuals accustomed to Western cultural customs threatening, rude, or culturally unacceptable, to the extent that they retreat into silence or become unable to continue with their evidence — see 3.3.4 above for more about some of these differences. Some cultures are lower touch cultures than Western culture, whereas other cultures tend to be higher touch.

3.3.5.4 Explain court proceedings adequately

People who come from countries with completely different legal and/or court systems are likely to find the Australian legal and court system confusing, incomprehensible and/or even threatening.

3.3.6 The impact of different customs and values in relation to such matters as family composition and roles within the family, gender, marriage, property ownership and inheritance

3.3.6.1 Background information

-

Each culture has its own customs and values in relation to such things as family composition, the role of the family versus the individual, individual roles within the family, gender roles, marriage, property ownership and inheritance.

-

Often customs and values are heavily influenced by the particular religious affiliation/s of an ethnic group or sub-group. For more on religious affiliations, see Section 4.

-

These sets of customs and values can be slightly different or very different from Western cultural customs.

-

Just as there are sub-cultures among Australians accustomed to Western cultural customs that have slightly or completely different customs and values about these fundamental aspects, and also families or individuals who do not seem to follow any particular cultural customs, there are similar examples within any other culture. So, it is important not to assume that everyone who is, for example, Arabic will adhere to a similar set of values or customs, or even to assume that everyone born, for example, in Lebanon will adhere to the same customs and values, or even to assume that all Christian Lebanese people will adhere to the same set of customs and values.

-

In addition, many people from culturally diverse backgrounds have varied their customs and values from those in their home country, in order, for example, to adapt to having a smaller family here, or to adapt to mainstream Western customs and values, (for example, to have a better chance of succeeding in a professional environment – see the comment on “code-switching” in 3.2.1 above),67 or because they are now in families comprising members from different ethnic backgrounds. In the reverse, some older generations within ethnic communities may hold fast to customs and values that have in fact shifted in their own home countries.

-

There may also be considerable inter-generational conflict as younger generations move away from the customs and values of their parents’ generation.

-

Similarly there may be considerable conflict or problems within mixed race families — for example, disinheritance, inability to negotiate differences of opinion about fundamental aspects of custom and values, vulnerability of one partner due to their lower level of English or not having any of their own birth family members in Australia.

3.3.6.2 Examples of different customs and values68

-

In almost all diverse cultures, the family is regarded as central and one of the most important parts of upholding the particular group’s traditions and culture.

-

In many diverse cultures the family comes before the individual. For example69 in many Vietnamese families, Confucian values require members of the family to act according to their roles in the family, including by fulfilling duties to other relatives and ancestors. Family members’ distinct roles are reflected in the language, where most family members have a title indicating their position within the family group (eg among some Vietnamese groups, Anh Hai (“second brother”) is the title given to the eldest brother, with corresponding titles continuing down the line of siblings).

This concept of the family before the individual may even extend to the “collective” or social group needing to come before the individual.

-

Larger families and extended family networks. The family in some cultures is often much broader than the Western concept of the nuclear family of parents and children. The extended family may include aunts, uncles, siblings, nieces, nephews, cousins, grandparents, grandchildren and even in-laws and their families. Marriage and other such religious and cultural rituals may also be used to expand the family networks even further, drawing in people such as the best man or woman at a marriage, or a sponsor at a baptism.70

For example, for Greek people, “the best man at weddings or the sponsor at a child’s baptism (“Koumparos”) is considered a spiritual relative and enters lasting and binding commitments. Similarly, the sponsor of “Kivrelik” (the ritual performed through the rite of circumcision) becomes a part of the family of the young male and assumes duties related to his education and wellbeing .

There may also be strong obligations to overseas family members including the need to send money overseas, the need to sponsor family members into Australia, and the need to arrange marriages between people resident in Australia and people currently resident in the country of origin.

-

A greater sense of the male as head of the family, with women taking more subordinate roles than men and maybe not allowed or expected to own or even jointly own property or inherit family assets, although there are also some cultures which are, or have been, matriarchal and others where women’s matrimonial property rights are legally protected. The sons in the families of some cultures may also have specifically defined roles.

-

Different courtship and marriage customs including arranged marriages where the partner may be sought from overseas not just from within Australia, a dowry needing to be provided by the family of the bride, overseas polygamous marriages, and/or a very strong push to marry within the particular ethnic group. In many families from culturally diverse backgrounds, the choice of marriage partner is a family not a personal decision. For some of these families, marriage outside the community or family wishes could lead to exclusion from the family and/or community.

-

In some instances, less tolerant views about such things as de facto relationships, having children outside a marriage, abortion, and/or homosexuality. This may be more likely to be the case where the religion (or denomination or branch of religion) practised by the particular family group is not tolerant of such things — see Section 4.

-

Grandparents frequently live with and are cared for by a member of the family and different cultures assign the caring responsibility to different members of the family.

Allied to the stronger concepts of family, there may be stronger “concepts of family honour and shame”71 which may act as a significant means of control and rationale for why members of particular cultural groups act as they do.

These concepts also impact on whether family members attend court to support an individual facing a court sentence.

-

More extreme differences in behaviour and/or appearance between different levels, classes or “castes”.

3.3.6.3 Ways in which you may need to take account of these different customs and value

3.3.7 Directions to the jury — points to consider

As indicated at various points in 3.3 above, it is important that you ensure that the jury does not allow any ignorance of cultural difference, or any stereotyped or false assumptions about people from particular culturally diverse backgrounds to unfairly influence their judgment.

3.3.8 Sentencing, other decisions and judgment or decision writing — points to consider

3.4 Further information or help

-

Interpreting and translating services — see 3.3.1.3 above.

-

The following NSW government agency can provide further information or expertise about migrant or ethnic communities and their cultural or language differences or needs, and also about other appropriate community agencies, individuals, and/or written material, as necessary.

Multicultural NSW

PO Box 618

Parramatta NSW 2124

Ph: (02) 8255 6767

contact@multicultural.nsw.gov.au

https://multicultural.nsw.gov.auTranslating and Interpreting Service (TIS National)

GPO Box 241 MELBOURNE VIC 3001

Ph: 131 450

www.tisnational.gov.auCultural Advice

Local agencies such as a Migrant Resource Centre, or an ethno-specific cultural organisation may also be useful sources of further information.Judicial Council on Diversity and inclusion

PO Box 4758

Kingston ACT 2604

Ph: (02) 6162 0361

Email: secretariat@jcdi.org.au

www.jcdi.org.au

3.5 Further reading

Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration Inc, Bench Book for Children Giving Evidence in Australian Courts, 2020, Melbourne, accessed 30/8/2023.

Australian Bureau of Statistics website, accessed 30/8/2023.

Australian Law Reform Commission, Multiculturalism and the law, ALRC Report No 57, 1992, Canberra, accessed 30/8/2023.

H Bowskill, “The Judicial Council on Diversity and inclusion — an update”, (2023) 35(4) JOB 33, accessed 6/9/2023.

J Downes, “Oral Evidence in Arbitration”, speech to the London Court of International Arbitration’s Asia-Pacific Users’ Council Symposium, Sydney, 14 February 2003, accessed 30/8/2023.

R French, “Equal justice and cultural diversity — the general meets the particular”, paper presented at the Judicial Council on Cultural Diversity, Cultural Diversity and the Law Conference, 14 March 2015, Sydney, accessed 30/8/2023.

S Hale, The discourse of court interpreting, John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, 2004.

S Hale, “Helping interpreters to truly and faithfully interpret the evidence: the importance of briefing and preparation materials” (2013) 37(3) Aust Bar Rev 307.

S Hale, “Interpreter Policies, Practices and Protocols in Australian Courts and Tribunals: a National Survey”, Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration Inc, 2011 at www.aija.org.au/online/Pub%20no89.pdf, accessed 30/8/2023.

S Hale and L Stern, “Interpreter quality and working conditions: comparing Australian and international courts of justice” (2011) 23(9) JOB 75.

S Hale, “The challenges of court interpreting — intricacies, responsibilities and ramifications” (2007) 32(4) Alternative Law Journal 198.

S Hale (ed), Translation & Interpreting, The international journal of translation and interpreting research, accessed 15 May 2013.

Judicial Council on Cultural Diversity, Recommended National Standards for working with interpreters in courts and Tribunals, 2017, accessed 30/8/2023.

MD Kirby, “Judging: reflections on the moment of decision” (1999) 4 TJR 189.

J Kowalski, “Managing courtroom communication: reflections of an observer”, (2008) 20(10) JOB 81.

E Kyrou, “Hot topic: judging in a multicultural society” (2015) 2(3) Law Society of NSW Journal 20.

W Martin, “Access to justice in multicultural Australia”, paper presented at the Judicial Council on Cultural Diversity, Cultural Diversity and the Law Conference, 13 March 2015, Sydney.

S Mukherjee, “Ethnicity and crime”, Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice No 117, May 1999, Australian Institute of Criminology, accessed 30/8/2023.

National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters, website , accessed 30/8/2023.

M Perry and K Zornada, “Working with interpreters: judicial perspectives”, paper presented at the Judicial Council on Cultural Diversity, Cultural Diversity and the Law Conference, 13 March 2015, Sydney, accessed 30/8/2023.

Judicial Commission of NSW, Sentencing Bench Book, 2006, under “Race and ethnicity”, at [10-470], accessed 30/8/2023.

L Re, “Oral evidence v written evidence: The myth of the ‘impressive witness’” (1983) 57 ALJ 679.

Supreme Court of Queensland, Equal Treatment Benchbook, 2nd ed, 2016, Supreme Court of Queensland Library, Brisbane, Chapters 4 and 6, accessed 30/8/2023.

D Tran, “Vietnamese community” (2002) 5(4) TJR 359.

3.6 Your comments

The Judicial Commission of NSW welcomes your feedback on how we could improve the Equality before the Law Bench Book.

We would be particularly interested in receiving relevant practice examples (including any relevant model directions) that you would like to share with other judicial officers.

In addition, you may discover errors, or wish to add further references to legislation, case law, specific Sections of other Bench Books, discussion or research material.

Section 15 contains information about how to send us your feedback.

1Multicultural NSW, website, accessed 23/08/2022.

2Unless otherwise indicated, the statistics in 3.1 are drawn from Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2021 census data QuickStats and Snapshot of NSW, accessed 23/8/2023.

3The ABS states: “The list of main English-speaking countries (MESC) is not an attempt to classify countries on the basis of whether or not English is the predominant or official language of each country. It is a list of the main countries from which Australia receives, or has received, significant numbers of overseas settlers who are likely to speak English. It is important to note that being from a non-main English-speaking country does not imply a lack of proficiency in English.” “Other than main English-speaking countries” (OTMESC) are defined as non-main English-speaking countries comprising all countries that are not listed above: ABS, “Glossary”, Migrant data Matrices,released 15/12/2021, accessed 23/8/2023.

4The ABS generally classifies proficiency in spoken English (that is “the ability to speak English in every day situations”) as: very well, well, not well or not at all. See ibid.

5ABS, Cultural diversity of Australia, 20/9/2022, accessed 23/8/2023.

6ABS, Migration, Australia, 2019–20 financial year, released 23/4/2021, accessed 23/8/2023.

7ABS, Snapshot of New South Wales, 2021, released 28/6/2022, accessed 18/7/2023.

8UNSW and ACOSS, Poverty in Australia 2023: who is affected, p 57. Note that MESCs are referred to as “major English-speaking countries” in this report.

9OECD, Data, Migration, native-born unemployment and foreign-born unemployment, accessed 23/8/2023.

10Australian Government, Jobs and Skills Australia, Australian labour market for migrants — July 2023, p 3, accessed 18/7/2023.

11ibid, p 5.

12ibid, p 4.

15ABS, Characteristics of recent migrants, Australia, Nov 2019, ABS cat no 6250.0, Table 2, accessed 23/8/2023.

16S Mukherjee, “Ethnicity and Crime”, Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice No 117, May 1999, Australian Institute of Criminology, accessed 23/8/2023; S Poynting, G Noble, P Tabar, Middle Eastern appearances: “Ethnic gangs”, moral panic and media framing (2001) 34 Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 67.

17Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4517.0 — Prisoners in Australia, 2022, accessed 23/8/2023.

18Hackett (A pseudonym) v Secretary, Dep of Communities and Justice [2020] NSWCA 83 at [149].

19Diversity Council Australia, Culturally and racially maginalised women in leadership, Synopsis report, March 2023, p 22, accessed 19/7/2023.

20L Berg and B Farbenblum, “As if we weren’t humans: The abandonment of temporary migrants in Australia during COVID-19”, Migrant Worker Justice Initiative, 2020.

21Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002, s 3.

22Premier’s Memorandum M2012-01 Policy on Identity and Full Face Coverings for NSW Public Sector Agencies and the policy on Identity and Full Face Coverings, developed by the then Community Relations Commission (now Multicultural NSW), addresses the need for laws that allow for the identification of people in certain circumstances. The Identification Legislation Amendment Act 2011 amended the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002, the Court Security Act 2005 and the Oaths Act 1900 to permit particular officers to require, in certain circumstances, the removal of a face covering.

23Much of the information in 3.3 is sourced from the Judicial Council on Cultural Diversity and Inclusion, Recommended national standards for working with interpreters in Courts and Tribunals, 2022, 2nd ed, accessed 29/8/2023; Supreme Court of Queensland, Equal Treatment Benchbook, 2016, 2nd ed, Supreme Court of Queensland Library, Brisbane, accessed 3/3/2023; Chapter 6; the National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters (NAATI) website.

24NAATI, “Certification glossary of terms”, accessed 19/7/2023.

25ibid.

27ibid, Sch 1, pp 27–28.

28AUSIT, Code of ethics, November 2012, accessed 19/7/2023.

29ASLIA, Code of ethics and guidelines for professional conduct, 2007, revised 2020, accessed 19/7/2023.

31(1998) 196 CLR 354 at [82]–[83]. See also Dietrich v The Queen (1992) 177 CLR 292 at 330-1; Ebatarinja v Deland (1998) 194 CLR 444 at [27]; R v Johnson (unrep, 22/5/87, QCCA) and Adamopoulos v Olympic Airways SA (1991) 25 NSWLR 75 at 75–77.

33This question is derived from the JCDI, Recommended national standards , above n 23, p 96ff.

35See both the online and in person training the JCDI provides for judicial officers on working with interpreters on its website. See also a summary of the publication in (2018) 30(4) JOB 36.

36JCDI, Interpreters in criminal proceedings: benchbook for judicial officers, August 2022, accessed 25/7/2023.

37See NAATI’s online directory for a list of accredited translators and interpreters, accessed 3 March 2023. The NAATI website provides online verification of NAATI certification. See also JCDI above n 23, p 90.

38(1993) 70 A Crim R 515 at 516.

39Recognised Practising is an award in a totally separate category from certification. It is granted only in languages for which NAATI does not test and it has no specification of level of proficiency. Recognised Practising does not have equal status to certification, because NAATI has not had the opportunity to testify by formal assessment to a particular standard of performance. It is, in fact, intended to be an acknowledgment that, at the time of the award, the candidate has had recent and regular experience as a translator and/or interpreter, but no level of proficiency is specified. Source: www.naati.com.au, accessed 3 March 2023.

41ASLIA, Guidelines for interpreters in legal settings, vers 2, 2018, accessed 6/3/2023.

43See further M Painting, “The new national certification system for the translating and interpreting profession in Australia” (2019) 31 JOB 63.

45The Code of Ethics and a register of members are available on the AUSIT website, accessed 22/2/2023.

46S Hale, “Helping interpreters to truly and faithfully interpret the evidence: the importance of briefing and preparation materials” (2013) 37(3) Aust Bar Rev 307.

47UNSW, “Access to justice in interpreted proceedings: the role of judicial officers”, accessed 22/2/2023.

48See the Multicultural NSW website.

49Local Court of NSW, Annual review 2022, 3/7/2023, p 41, accessed 2/8/2023.

50Refer to the JCDI, above n 23, “Recommended standards for judicial officers”, pp 19–20; “Annexure 5 — Summary: what judicial officers can do to assist the interpreter”, p 98.

52ibid, p 98.

53ibid, p 22.

54ibid pp 45, 98.

55S Hale, The discourse of court interpreting, John Benjamins Publishing Co, 2004.

56See s 26 Evidence Act 1995 (NSW), on dealing with the court’s control over questioning of witnesses.

57S Hale, “The challenges of court interpreting: intricacies, responsibilities and ramifications” (2007) 32(4) Alt LJ, pp 198-202.

59D Tran, “Vietnamese community” (2002) 5(4) TJR 359 at p 362.

60See s 3 (the definition of “face covering”) Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002.

61See Goodrich Aerospace Pty Ltd v Arsic (2006) 66 NSWLR 186 at [21]–[27]. See also, L Re, “Oral evidence v written evidence: the myth of the ‘impressive witness’” (1983) 57 ALJ 679; M Kirby, “Judging: reflection on the moment of decision” (1999) 4(3) TJR 189 at 193–4; and Downes J, “Oral evidence in arbitration”, speech to the London Court of International Arbitration’s Asia-Pacific Users’ Council Symposium, Sydney, 14 February 2003, accessed 30/8/2023. Kirby J also addressed this theme in a judicial context in State Rail Authority of NSW v Earthline Constructions Pty Ltd (in liq)(1999) 160 ALR 588.

64Note that s 41 Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) provides for the statutory control of improper cross-examination in both civil and criminal proceedings. The section is in line with the terms of the repealed s 275A Criminal Procedure Act 1986, rather than the common law position. Section 41 imposes an obligation on the court to disallow a “disallowable question” and is expressed in terms of a statutory duty whether or not objection is taken to a particular question (s 41(5)). A “disallowable question” is one which is misleading or confusing (s 41(1)(a)), unduly annoying, harassing, intimidating, offensive, oppressive, humiliating or repetitive (s 41(1)(b)), is put to the witness in a manner or tone that is belittling, insulting or otherwise inappropriate (s 41(1)(c)), or has no basis other than a stereotype (s 41(1)(d)). A question is not a “disallowable question” merely because it challenges the truthfulness of the witness or the consistency or accuracy of any statement made by the witness (s 41(3)(a)) – or because the question requires the witness to discuss a subject that could be considered distasteful to, or private by, the witness (s 41(3)(b)). Sections 26 and 29 Evidence Act also enable the court to control the manner and form of questioning of witnesses, and s 135(b) allows the court to exclude evidence if its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger that the evidence might be misleading or confusing.

66ibid.

68Much of the information in 3.3.6.2 is sourced from the Supreme Court of Queensland, Equal Treatment Benchbook, above n 23.

69ibid, p 22, drawing on R T Schaefer (ed), Encyclopedia of race, ethnicity and society, Sage Publications, 2008, p 477; A Fauve-Chamoux and E Ochiai, “Introduction” in A Fauve-Chamoux and E Ochiai (eds), The stem family in Eurasian perspective, Peter Lang AG, 2009, p 1, 30; K Thu Hong, “Stem family in Vietnam” in A Fauve-Chamoux and E Ochiai (eds), The stem family in Eurasian perspective, Peter Lang AG, 2009, pp 431, 448–9.

70ibid, p 22, quoting S Sarantakos, Modern families: an Australian text, Macmillan Education Australia, 1996, p 69.

71ibid, p 40.

74Judicial Commission of NSW, Criminal Trial Courts Bench Book, 2nd edn, 2002 accessed 30/8/2023, and www.judcom.nsw.gov.au.

75Judicial Commission of NSW, Local Courts Bench Book, 1988 and www.judcom.nsw.gov.au, accessed 30/8/2023.

76See also Judicial Commission of NSW, Sentencing Bench Book, 2006, “Race and ethnicity” at [10-470], accessed 30/8/2023, and R v Henry (1999) 46 NSWLR 346 at [10]–[11].

77See Pt 3, Div 2 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW) and the Charter of Victims Rights contained in Div 2 Victims Rights and Support Act 2013 (which allows the victim access to information and assistance for the preparation of any such statement). Note that any such statement should be made available for the prisoner to read, but the prisoner must not be allowed to retain it.