Older people

It is estimated that by 2036, over one in five people in NSW (21%) will be aged over 65 years. Older people are not a homogenous group. The purpose of this chapter is to:

-

highlight for judicial officers relevant information about the differences in education, health, accommodation, geographic isolation, mobility and cultural and linguistic backgrounds of those aged over 65, including the problem and prevalence of elder abuse, and how they may impact an older person’s access to justice, and

-

provide guidance about how judicial officers may take account of this information in court — from the start to the conclusion of court proceedings. This guidance is not intended to be prescriptive.

Introduction

The concept of “older person” is not statutorily defined, unlike a “child” who is legally defined by age criteria.1 For the purposes of this chapter, we have used Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) taxonomy, which groups people into population age cohorts, and differentiates between “15–64”, “65 years and over” and “85 years and over”. People over 65 are generally classified as “older” for ABS purposes.2 Very old persons are 85 years and older. All references are to chronological age, rather than reflecting an individual’s physiological and functional state.3

The life expectancy for Aboriginal people is about 20 years less than the rest of the Australian population. Aboriginal Australians account for only one-half of one per cent (0.5%) of people 65 years and older.4 Ageing can occur at a younger age and be more debilitating.5

Older people are therefore an extremely diverse group, as this term often refers to people up to 25 years apart in age. Differences in education, health, geographic isolation, mobility and cultural and linguistic background can make a vast difference between those at 65 and those at 85. In many cases, ageing issues also reflect those faced by people with disabilities 5.1 and age can exacerbate issues faced by those with ethnic or migrant backgrounds Chapter 3.1 and Aboriginal people Chapter 2.1.

The Commonwealth government has identified demographic trends which indicate that between 2010 and 2050, the 65 to 85 year cohort is expected to double and the 85 plus cohort is expected to more than quadruple from 0.4 million people today to 1.8 million people in 2050.6

It is important not to make assumptions about the capacity of an older person based on their age. Ageist attitudes, in other words, stereotyping someone on the basis of their age, is regarded as one of the main contributing factors to various forms of exploitation, abuse and neglect of some older people.7

11.1 Some information

11.1.1 Population

-

In 2016, 16% of the population in NSW, or 1,217,261 people, were aged 65 and older (out of total population of 7,739,274). This reflects national trends where 15% (3.7 million) Australians were aged 65 and over. This proportion is projected to grow steadily over the coming decades.8

-

In NSW, 537,240 people were 75 and older and 166,065 people were 85 and older. The proportion of people in NSW aged 75 and older is more than the 0-4 age group (500,970) and those over 65 years (1,217,261) nearly outnumber those in the 0-14 age group (1,452,958).9 Nationally, 56% of older people are between the ages of 65 and 74.10

-

It is estimated that by 2036, over one in five people in NSW (21%) will be aged over 65 years. 11

-

In terms of cultural diversity, NSW was the most popular State or Territory to live in 2016 (2,072,454 people or 34% of the overseas-born population).12

-

In NSW in the year ending 30 June 2018, the percentage of people aged over 85 years increased by 1.9%, compared to the national average of 2.2%.13 The proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 65+ was considerably smaller than for non-Aboriginal people (4.8% compared to 16%).14

-

Compared to other States and Territories, NSW has received a relatively small increase in people aged 85 years and over (1.9%), compared to the Northern Territory (6.1%), WA (3.6%) and Victoria (2.6%).15

11.1.2 Education

The level of education often impacts a person’s ability to understand and access the legal system. This includes their ability to access technology (see further 11.4.1 Barriers — Access to justice).

-

In NSW in 1925, there were only 34 high schools, increasing to 184 by 1960 and 397 high schools by 2005.16

-

This helps explain national trends that those in the 65–74 years age group were more likely to have a non-school qualification than those over 85 (46% and 27% respectively) and were also more likely to have completed year 12 equivalency (37% and 25%).17

-

Whether they were in the work force or not, older people with higher levels of education were more likely to have a higher personal median income. Older people with a non-school qualification were twice as likely to still be in the labour force as those without (20% and 9.9% respectively).18

11.1.3 Employment

-

Australians are increasingly working to older ages. The work status of those aged over 50 in NSW varies significantly between age cohorts. Two-thirds (64%) of those aged 50–60 are currently employed, whereas over half (61%) of 61–69 year olds are retired. Of those aged 70–79, 90% are retired and 8% are working.19

-

More than half of all employed older people in NSW worked part-time.20 No longer wanting to work is the most common reason those over 60 have chosen to retire, particularly among retirees in their 70s (48%). Declining physical capability was also an issue for a quarter of 61–69 and 70–79 year olds (24% and 23% respectively). Almost one in five (17%) of those who are still working in their 70s do not intend to retire, significantly more than the other two age cohorts.21

-

Ageism in the workplace presents a greater fear among those in their 50s and 60s. In NSW, over one-third (37%) of workers in their 50s think the attitudes of their employers towards old people will prevent them from working as long as they would like to. In comparison, few (10%) in their 70s believe this to be a likely scenario.22

-

27% of those aged over 50 years experienced a form of age discrimination in the past two years. Of this percentage, 33% were completely discouraged from looking for employment as a result of the discrimination.23

11.1.3.1 Volunteering and unpaid work

-

In NSW, two in five (39%) older people participate in volunteering activities, with those in their 70s being significantly more likely to do so.24 Over half (51%) are volunteering for welfare and community organisations. Motivating factors are to do something worthwhile (76%), to help others and the community (74%) and personal satisfaction (69%).25

-

Nearly one in five (19%) older people were engaged in unpaid childcare for a child (under 15 years) who was not their own. Between 2006 and 2016, women aged 65–74 years experienced the greatest increase in this area (18% to 22%).26 Grandparents provided care for 18% of all children aged 0–11 years.27 See further 11.1.7 — Grandparents.

11.1.4 Income

A person’s earning capacity generally increases with age, however falls sharply after 64 years of age.

-

In NSW, the work status of those aged over 50 varies significantly between age cohorts. Two thirds (64%) of those in their 50s are currently employed, whereas a similar proportion (63%) of those in their 70s are retired. Half (51%) of those in their 60s are retired and one third (32%) are working.28

-

Access to superannuation to supplement the age pension has become increasingly prevalent. In 1997, 12% of retired Australians aged 45 and over stated that superannuation was their main source of income, compared with 25% in 2016–17. However, as compulsory superannuation only began in the 1980s, older people have not yet fully benefited from the scheme: the proportion of people aged 70 and over in 2007 who had never had superannuation coverage was 41% for males and 75% for females.29

-

96% of low and 88% of middle wealth retiree households (households where the reference person was 65+ and not in the labour force) source their income from government pensions and allowances. However, 66% of high wealth retiree households receive income from other sources (ie superannuation).30

11.1.5 Health

Life expectancy for older people is increasing, however with this has come an increase in the expected years of life with medical issues or a disability.

-

The leading cause of death for all older Australians nationally was coronary heart disease — 51,600 deaths between 2014 and 2016, followed by dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (37,400 deaths), cerebrovascular disease (29,800), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (19,500) and lung cancer (19,200). Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease featured as the second leading cause of death among people aged 75 and older.31

-

Long-term health conditions most frequently reported were eyesight problems (81%), arthritis (48%), hypertension (41%) other circulatory diseases (33%) and hearing problems (33%).32

-

63% of older people in NSW rate their mental health as very healthy, although only 32% rate their physical health the same.33

-

Dementia affects 10% of people in NSW aged over 65 years and 31% of people aged over 85 years.34

-

Studies consistently show that people with dementia have an increased risk of death due to complications and causes directly or indirectly related to dementia. Between 2014–2016, 10% of deaths of people in NSW aged 65 and over were due to dementia, with the number of deaths increasing with age, although there was a decline in deaths due to dementia for people aged 95 years and over.35

-

In NSW, the highest age-specific suicide rate is in men aged 85 years or older (37.6 per 100,000). Comparatively this rate is significantly lower for women aged 85 and older (6.5 per 100,000) and men aged 65-69 (16.4 per 100,000).36

-

Given the older prison population, and the fact that there is a 10-year differential between overall health of prisoners and that of the general population, older prisoners are more likely to experience premature ageing disease and disability, including dementia. There are other risk factors, both before and after incarceration that increase their risk, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, drug and alcohol abuse, low socio-economic status and inadequate access to health care.37

A number of medical and socio-economic conditions may impact on the cognitive ability of an older person, and may be permanent or temporary. Reference should be made to 5.2.5 — Making adjustments for people with disabilities.

Health, income and accommodation can be linked. The sometimes precarious nature of renting in the private rental market, where no social housing is available, has more profound negative impacts on the health and quality of life of older people than the general population.38 This is due, in part, to the relatively large amount of time older people spend inside their home. It is especially so for those with a disability (including a disability such as dementia) or other health and mobility issues. Older people have a greater likelihood of ill health, disability, widowhood and living alone, in addition to low incomes. See further 11.1.8 — Accommodation and living arrangements.

11.1.6 Care and assistance

-

As people age, they are more likely to require assistance with everyday activities such as household chores, transport and health care tasks, although the proportion of older people with a disability decreased from 2012 to 2015. In NSW in 2015, there were a total of 857,200 carers (12% of population). Nationally, nearly 1 in 5 (18.4%) of older people were carers in 2015. Of this percentage, 37% were a primary carer; 86% of older primary carers were caring for a spouse or partner. 39

-

Over the next 30 years, in NSW the number of carers is projected to rise by 57% while the number of aged people needing care will rise by 160%.40

-

The proportion of older people who use aged care (which includes home support, home care packages and residential care) increases markedly as they age. Around 1.3% of 70-year-olds use home care or residential care; this compares to around 15 % of 85-year-olds and 50% of 95-year-olds. These services cost around $20 billion each year.41 The current expected wait times for approved home care packages is generally 12+ months.42

-

In 2009, 25.6% of older people fell at least once in the last 12 months.43

-

Alongside population growth, in NSW the number of older people with a diagnosable mental illness is projected to increase from approximately 190,000 in 2016 to 260,000 in 2026.44

-

As of 2016, 87% of older people living in non-private dwellings reported a need for assistance (ie for mobility, communication or self-care).45

-

Older people received 79% of all Home and Community Care Services in NSW in 2002–2003 (commonly domestic assistance, transport, home care service assessment and home meal services).46

-

Participation in unpaid carer roles affects an older person’s capacity to remain in paid work. As of 2015, 41.5% of older primary carers in NSW spent an average of 40 hours or more per week in a caring role. One in eight older carers who were not in the labour force reported the main reason for leaving work was to commence a caring role.47

11.1.7 Grandparents

Grandparents as parents — Child Care and Protection and the Family Law Act

-

In 2017, 17,387 children in NSW were in formal out-of-home care (nationally 45,756). Of those, 51% were in relative/kinship care. The majority of children in relative/kinship care at 30 June 2017 were placed with grandparents (52%), 20% were placed with an aunt/uncle, and 17% in a non-familial relationship.48

-

Of these numbers, 95% of children in out-of-home care were also on care and protection orders. It is important to note that these statistics relate only to formal kinship care, and do not include unofficial kinship care where the care of children has been arranged by the family without involvement of child protection or welfare authorities. Maternal grandmothers are the most frequent caregivers of children in out-of-home care.49

-

At 30 June 2021, 6,829 First Nations children in NSW were in out-of-home care (16 times the rate for non-Aboriginal children). The rate has increased by 4% since 2018, and First Nations children make up 43% of all children in the system.50 Across Australia, in 2017–18, 65% of First Nations children were placed with relatives/kin, with other First Nations caregivers, or in Aboriginal residential care. These informal arrangements will have multiple effects on the grandparent caregiver, including financial, physical and mental health.51

-

All these figures exclude “baby-sitting/child-care” arrangements undertaken by grandparents for their working children.

-

There are no current statistics on the number of parenting orders under the Family Law Act 1975 that have been dealt with by the Family Court. Available cases suggest that it is unusual to see intervention by grandparents and circumstances are generally confined to those cases which see grandparents fulfilling roles which parental absence (such as death of a parent or incarceration), illness or dysfunction.52 In parenting orders, grandparents will have reasonable prospects of success only when they are opposing everyone else and there are cogent, child-focussed reasons referenced to in s 60B(2) of the Family Law Act for doing so.53

-

Many grandparents-as-parents in informal arrangements may need to cease their employment to look after their grandchildren or use their retirement savings to provide for their grandchildren.54

11.1.8 Accommodation and living arrangements

-

In NSW, the majority (71%) of individuals in their 60s currently live in a detached freestanding house. Nearly a fifth (19%) rent their home, and 17% still have a mortgage. The vast majority (80%) of 70-79 year olds live in a detached house. A similar proportion (84%) own their homes outright, with only 7% renting. Around three-quarters (76%) of those over 80 live in a detached (freestanding) house. The majority (86%) own their property outright and almost two-thirds (63%) have been living in their current property for more than 20 years. Nearly one in 10 (9%) are residing in a retirement village.55

-

Of the 60–79 year cohort in NSW, 24% are interested in living in a retirement village in the future. Nearly one in 10 (9%) of those aged over 80 currently reside in a retirement village.56

-

The quantity of public, community and Aboriginal housing is not keeping pace with increases in population. In NSW during April 2018, there were 55,949 on the waiting list for social housing, with wait times of a decade across much of the State. Older people are particularly vulnerable in the private rental market as they age. The current age for prioritisation (80 years) does not acknowledge the inherent risks to this group.57

-

In NSW, there was an estimated 15,126 people aged 50 and over who were currently living in marginal, temporary or improvised housing on census night in 2016. A report from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare also indicated that people aged 55 or older experiencing housing insecurity is increasing rapidly with a 3-fold increase compared to the general population in the year to 2016–2017.58

Coinciding with the increase in family accommodation agreements is an increase in instances of elder financial abuse in relation to family accommodation agreements. In 2016–17 the NSW Elder Abuse Helpline and Resource Unit received 1800 calls, of which 39% were related to financial abuse and 58% were related to psychological abuse, which often co-occurs with financial abuse.59 See further 11.2.3 — Succession/financial abuse.

11.1.9 Rural, regional and remote areas

-

Older people living in rural areas have the same information needs as those in urban areas, however access to information sources and services will differ because of the difficulties of travelling and the barriers of distance and time. This is particularly true for those living in remote areas.

-

The health of older people in rural and remote areas is generally poorer than that of older people living in metropolitan areas. Poorer health outcomes in rural and remote areas may be due to a range of factors, including a level of disadvantage related to education and employment opportunities, income and access to health services. 60

-

Overall, the more remote the area in which you live, the poorer your health status.

-

Twelve of the 20 least advantaged federal electoral divisions and 36 of the 40 poorest areas of Australia are classified as rural or remote.61

-

Factors such as social isolation, fewer economic means to plan for retirement, and limited access to transport, residential and community care, medical and preventive health care means that many rural older people are coping with these consequences by themselves.62

-

There is particular difficulty in attracting and retaining health and other professionals in rural, regional and remote areas, and the costs of constructing and operating facilities in remote areas can be prohibitive.

-

Access to transport is a key issue for older people, particularly in remote areas. Many older people do not have their own vehicle, whether because of disability or other impediments to their driving long distances, such as cost. Public transport is often non-existent, inconvenient or too expensive.63

-

It is generally recognised that the risk of loneliness in old age is higher among migrant and refugee populations, people with same-sex attraction or gender dysphoria and people living in rural and remote areas.64

-

While Australians of all backgrounds reside in the different regions across Australia, the Indigenous population has a much greater concentration in the more remote areas.65

-

Old age dependency ratios are higher in inner regional areas, reflecting trends for many Australians to leave major cities on retirement.66

11.1.10 Gender

-

Gender significantly affects experiences of ageing. Women have a longer life expectancy than men, but older women have relatively lower incomes and fewer assets than men.67 Contributing factors to this include lower average weekly ordinary time earnings for women (a 14.1% “gender pay gap” at February 2019), as well as career breaks to undertake unpaid care work.68

-

Women tend to have lower superannuation balances and retirement payouts than men.69 Approximately 60% of women aged 65–69 in 2009–2010 had no superannuation.70 Women also make up a greater proportion of age pension recipients. At June 2013, women comprised 55.6% of recipients. Of these, 60.8% received the full rate of age pension. At June 2013, women comprised 55.6% of recipients. Of these, 60.8% received the full rate of age pension.71

-

Stereotypes such as the man being the provider and protector of the family, and social and cultural norms that require men to show strength and resilience can dissuade men from acknowledging, seeking help or reporting abuse. Even when men do report abuse, there are not always adequate services to support them, as many family crisis centres are women-only services. Older men are also more likely to be socially isolated than women.72

11.1.11 Sex and gender diversity

Many older lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LGBTQI) Australians have faced a lifetime of discrimination and abuse and they fear this will continue. There is little data on the LGBTQI community among older people. According to the Census in 2016, there were around 23,700 male same-sex couples and 23,000 female same-sex couples.

-

Overall, only 5% of people in same-sex couples were aged 65 or over, compared with 20% of people in opposite-sex couples.73

-

People who have diverse sexualities, relationships, bodies and genders face particular issues as they age, and they face specific barriers to accessing aged care.74 For the first time, the 2016 Census allowed a choice of “other” in response to the question reporting sex in a way not limited to male or female. Approximately 1300 people chose to report their gender identity in this way.75 The most common identities provided were transgender, another gender and non-binary. Just under 6% of people who responded “other” were aged 65 and over, and this proportion is likely an underrepresentation due to the decreasing preference for online forms with age.76 It is important to note that a person who may have intersex characteristics generally identifies themselves as either male or female: see further Chapter 9 at 9.3.1.

11.1.12 Digital confidence

Among older Australians, those aged 50 to 69 are significantly more engaged with technology, understand its purpose and potential value. Those aged 70 and over are more digitally disengaged, citing lack of trust, confidence, skills and personal relevance. Older Australians generally use the internet to research about goods they would like to purchase, use internet banking, pay bills online and search for information about government services.77

-

While more than nine in 10 people aged 15–54 are internet users, the number drops to eight in 10 of those aged 55–64 years, and to under six in 10 of those over 65 years.78

-

In NSW, four in five (79%) people in their 70s feel they do not struggle keeping up with technology, although it is significantly more than those in their 50s (96%) and 60s (96%). 34% of those with a high school education (compared with 22% with a university education) feel they have struggled to keep up with technology.79

-

42% of 50–69 year olds have high digital literacy. Only 21% of 70+ age group have high digital literacy.80

-

According to the ABS, 43% of internet users aged 65 and over accessed the internet to engage with social media in the three months to June 2015. This compares to 72% for the national population aged 15 and over.81 88% of use of social media is Facebook.

-

In Australia, 15% of older internet users accessed government services, health and medical information online.

-

An estimated 1,000,000 adult Australians (6%) have never accessed the internet (as at June 2015). Older Australians account for the majority of this group — 71% of offline adults fall into the age group of 65 and over. Factors contributing to these figures include: living in country areas, being out of employment, having no tertiary education, having a lower income and are single/not married. 61% of these “offline” older people are women.82

-

Research in 2011 by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation found the key barriers preventing those over 65 from using the internet were a lack of skills, confusion by technology, and concerns about security and viruses.83

11.2 Elder Abuse

The problem and prevalence of elder abuse was recognised in Australia and overseas in the late 1980s. However, it was not until 2016 that the NSW Government inquired into elder abuse to develop a policy, legal and service framework to address the issue.84 The Australian Law Reform Commission completed an inquiry in 2017.85 Like other forms of abuse, abuse of older people occurs in institutional and domestic settings.

Elder abuse is generally described as “a single or repeated act, or lack of action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust which causes harm or distress to an older person”.86 While prevalence data in Australia is limited, estimates regarding the occurrence of elder abuse in NSW range from one in 20 people or 5%87 and nationally from 2% to 6% of the older population.88 This compares with reported rates of up to 14% internationally in high and middle income countries.89 These approximations are believed to underestimate the true extent of abuse in older populations.90

Internationally, five categories of elder abuse are recognised.91 These are:

- 1.

-

Physical abuse: Non-accidental acts that result in physical pain, injury or physical coercion.

- 2.

-

Sexual abuse: Unwanted sexual acts, including sexual contact, rape, language or exploitative behaviours, where the older person’s consent is not obtained, or where consent was obtained through coercion.

- 3.

-

Financial abuse: Illegal use, improper use or mismanagement of a person’s money, property or financial resources by a person with whom they have a relationship implying trust without the person’s knowledge or consent.

- 4.

-

Psychological/emotional abuse: Inflicting mental stress through actions and threats that cause fear or violence, isolation, deprivation or feelings of shame and powerlessness. These behaviours — both verbal and nonverbal — are designed to intimidate and are characterised by repeated patterns of behaviour over time, and are intended to maintain a hold of fear over a person. Examples include treating an older person as if they were a child, preventing access to services and emotional blackmail.

- 5.

-

Intentional and unintentional neglect: Failure of a carer or responsible person to provide life necessities, such as adequate food, shelter, clothing, medical or dental care, as well as the refusal to permit others to provide appropriate care (also known as abandonment).

The Australian Network for the Prevention of Elder Abuse recognises a sixth category of social abuse, which includes the forced isolation of older people, with the sometimes additional effect of hiding abuse from outside scrutiny and restricting or stopping social contact with others, including attendance at social activities.92

Psychological and financial abuse are the most common types of reported abuse, although one study suggests that neglect could be as high as 20% among women in the older age group.93 Frequently more than one type of abuse is suffered by the same person.

Elder abuse is underreported due to a range of internal and systemic barriers including family loyalty; fear of possible consequences/retribution; cognitive and/or physical barriers; lack of knowledge about access to support services or options; cultural, religious or generational barriers to seeking support; and literacy or language barriers: see further 11.4.1.

Elder abuse commonly occurs where the older person is dependent on another person for their daily needs.94

Research indicates women are more often victims of elder abuse than men, and this is disproportionate to the number of older women in the community. Data collected by helplines in Australia indicates that approximately 70% of elder abuse victims are women, although some research shows no significant difference in the rates men and women experience abuse, and older men were more likely to be victims of abandonment.95 Rates of abuse tend to increase with age.

Intergenerational abuse within the family is thought to be the most common form of elder abuse — notably by adult children, but also by the older person’s spouse or partner. Family violence exhibits similar dynamics. This is defined in s 4AB of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) as meaning “violent, threatening or other behaviour by a person that coerces or controls a member of the person’s family or causes the family member to be fearful”.

Risk factors in relation to being abused include:

-

dependence

-

significant disability or poor physical health

-

mental disorders (such as depression)

-

low income or socio-economic status

-

cognitive impairment

-

general inability to voice needs, and

-

social isolation.

Risk factors for committing abuse include:

-

depression

-

the toll of caregiving on the health and wellbeing of the carer

-

substance abuse/ alcohol and drug misuse

-

financial, emotional and relational dependence on the older person, and

-

a history of intergenerational abuse within families.96

In Aboriginal communities, perceptions about and experiences of elder abuse are complicated by family and community networks, cultural expectations relating to kinship structures, cultural values of sharing and reciprocity, and the extent to which grandparents, particularly grandmothers, are called upon to care for grandchildren.97

For some older culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) people, limited English skills may contribute to social isolation, increase dependence on family members, and in turn increase vulnerability to exploitation and abuse.98 Older people from CALD backgrounds are not homogenous, however in general, they have poorer socio-economic status compared with Anglo-Australians, and risk having differing cultural practices and norms which may lead to lack of understanding of and barriers to using services.99

Older lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LGBTQI) people may experience abuse related to their sexual orientation or gender identity. For example, an LGBTQI older person may be abused or exploited by use of threats to “out” a person. Abuse may be motivated by hostility towards a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity. Additionally, older LGBTQI people have a higher exposure to other risk factors for abuse: for example, they have a higher likelihood of diagnosis of treatment for a “mental disorder” or major depression than the general population of older people.100 They may also be at increased risk of social isolation, which may increase their vulnerability to abuse.

In the context of family violence, it has been suggested that in rural and regional areas, issues such as social and geographic isolation, limited access to support and legal services, as well as complex financial arrangements and pressures, including limited employment opportunities, may heighten vulnerability and shape the experience of violence.101

People with cognitive impairment or other forms of disability have been identified as being more vulnerable to experiencing elder abuse. Where a person has a disability, this will often be correlated with other risk factors, such as the need for support and assistance, as well as an increased likelihood of social isolation and lower socio-economic resources.102

Generally speaking, Australian State and Territory laws do not provide specific offences against older persons. However a range of types of conduct, which might be described as “elder abuse”, are covered in all jurisdictions under offence provisions relating to personal violence and property offences. These include assault, sexual offences, kidnap and detain offences, and property and financial offences. The Law Council of Australia noted that “elder abuse” is rarely prosecuted under existing provisions.103

Some jurisdictions have offences for neglect,104 although these are rarely utilised in respect of older people. These offences are generally framed as “failing to provide necessaries or necessities of life, including adequate food, clothing, shelter and medical care”. There are also comprehensive family violence frameworks in all jurisdictions that provide for quasi-criminal, protective responses to abuse of older people in domestic settings.105

In their critique of legal responses to elder abuse, Harbinson et al106 observe:

constructions of ageing that view older people as frail and vulnerable have led to a focus on providing legal remedies for mentally incapacitated older people, without the clear understanding that most older people are not mentally incapacitated.

In response to a number of reviews and inquiries highlighting the need for better safeguards for abuse, neglect and exploitation, the NSW government enacted the Ageing and Disability Commissioner Act 2019. The Act establishes a Commissioner, responsible for responding to abuse, neglect and exploitation of people with disability and the elderly in home and community settings. Its main functions include:107

-

Receiving, triaging and investigating allegations of abuse, neglect and exploitation.

-

Providing support to vulnerable adults and their families and carers during and following an investigation

-

Reporting and making recommendations to government on related systemic issues.

-

Raising community awareness — including how to prevent, identify and respond to matters.

-

Administering the Official Community Visitors program in relation to disability services and assisted boarding houses.

The Ageing and Disability Commissioner officially commenced on 1 July 2019. It is an offence for a person to take detrimental action against an employee or contractor who assists the Ageing and Disability Commissioner with a report about abuse, neglect or exploitation of an adult with disability or an older adult: s 15A.108

11.2.1 Abuse and neglect in residential care

Generally

There is no comprehensive data available on the prevalence of abuse of people in residential aged care. At 30 June 2020, a total of 189,954 people were using residential aged care (permanent or respite) and 58% of those were aged over 85 years.109 Abuse may be committed by paid staff, other residents in residential care settings, or family members or friends.

The 2019-20 Report on the Operation of the Aged Care Act 1997 indicates that during the 2019–2020 financial year there were 5,718 notifications110 (5,233 in 2018–2019)111 of reportable assaults as previously defined in the Act. Of those, 4,867 (4,443 in 2018–2019) were recorded as alleged or suspected unreasonable use of force, 816 (739 in 2018–2019) as alleged or suspected unlawful sexual contact, and 35 (51 in 2018–2019) as both.112 “Reportable assaults” captured a more narrow range of conduct, referring to “unreasonable use of force on a resident, ranging from deliberate and violent physical attacks on residents to the use of unwarranted physical force” and unlawful sexual contact, meaning any sexual contact with residents where there has been no consent”.113 Amendments made to the Act by the Aged Care Legislation Amendment (Serious Incident Response Scheme and Other Measures) Act 2021 now include eight types of conduct as a “reportable incident” (see below) under the Serious Incident Response Scheme (SIRS) which commenced 1 July 2021.

Media focus on cases of abuse by paid staff in residential care facilities has brought this issue to public attention.114 The Commonwealth Government announced the terms of reference for the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety on 9 October 2018. The Royal Commission delivered its final report of 148 recommendations, which was tabled in the Australian Parliament on 1 March 2021.115

Under the 2021 amendments to the Aged Care Act 1997 (Cth), which introduced the SIRS, s 54-3 was introduced and defined new terms for the reporting of certain incidents.116 New ss 54-4 to 54-8 establish protections to ensure disclosers are supported and protected in making disclosures of information. These protections are intended to promote integrity and accountability of approved providers in providing supports and services and to safeguard care recipients.117 The definition of a “reportable incident” is far broader than the previous “reportable assault” and includes any of the following incidents that have occurred, or alleged or suspected to have occurred to a residential aged care recipient in connection with the provision of care or flexible care in a residential setting:

-

unreasonable use of force;

-

unlawful sexual contact or inappropriate sexual conduct;

-

psychological or emotional abuse;

-

unexpected death;

-

stealing or financial coercion by a staff member of the provider;

-

use of “restrictive practice”, other than in circumstances set out in the Quality of Care Principles;

-

neglect; or

-

unexplained absence from the residential care services provider: s 54-3(2).

“Restrictive practices” in s 54-9 in relation to a care recipient is any practice or intervention that has the effect of restricting the rights or freedom of movement of the care recipient.

New reporting requirements as part of SIRS mean that residential aged care providers will be required to report and manage all serious incidents which impact on the safety and well-being of consumers, with the range of serious incidents that are reportable under SIRS being broader than those under previous compulsory reporting requirements.118

Sexual abuse in residential care

In 2019-20, there was notification of 816 alleged or suspected unlawful sexual contacts occurring in residential aged care facilities across Australia. This amounts to 2.3% of those in permanent residential care.119 Reports of sexual assault in aged care settings are often dismissed or not appropriately followed up due to procedural difficulties experienced, particularly where the victim is suffering from a cognitive or communicative impairment, mental illness or physical disability.120

11.2.2 Family violence

For many older people, domestic violence has been considered a “family matter” in which police would rarely intervene, and has not historically been treated as a criminal offence. Given these preconceived views, and the fact that the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 envisages that AVOs can be made following formal application or as a consequence of a person being charged, older people may be unaware or unwilling to apply for an ADVO or APVO. Like all cases of family violence, the matter may be complicated by fear of losing their home or income, intergenerational violence, and dependency on adult children to provide care.121

Older people may seek protection from family violence under the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW). The Justice Legislation Amendment Act (No 3) 2018 amended the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 by inserting s 5A to provide that a personal violence offence by a paid carer against a dependant is treated as a domestic violence offence and an ADVO may be made for the dependant’s protection. However, a personal violence offence committed by a dependant against a paid carer is not a domestic violence offence. The paid carer may still apply for an apprehended personal violence order against the dependant.

Under s 27 of the Act, it is mandatory for police to apply for an ADVO if the police officer suspects or believes that a domestic violence offence or stalking or intimidation offence has been or is likely to be committed. The effect of s 5A is that this continues to be the case where a paid carer is alleged to have committed a domestic violence offence against a dependant, but it will no longer be mandatory where it is alleged that a dependant has committed a domestic violence offence against a paid carer. These amendments commenced 17 December 2018.

The vulnerable witness provision may apply to an older person in APVO and ADVO proceedings if the older person is cognitively impaired. Section 306ZB of the Criminal Procedure Act 1986 (NSW) permits a vulnerable person to give evidence in apprehended violence proceedings by CCTV, unless he or she is the defendant. A “vulnerable person” is a child or cognitively impaired person: s 306M(1). Refer to [22-100] of the Local Court Bench Book in relation to procedures for evidence from vulnerable persons — Div 4, Pt 6, Ch 6 Criminal Procedure Act 1986 applies to proceedings in relation to the making, variation or revocation of AVOs: s 306ZA.

11.2.3 Succession/financial/capacity abuse

This is the most reported form of elder abuse, regarded as vastly unreported. Financial abuse is regarded as the “illegal use, improper use or mismanagement of an older person’s money, financial resources, property or assets without the person’s knowledge or consent”.122 It includes misuse of powers of attorney123 by spending an older person’s money in ways not in their best interests or for personal gain; coercing an older person to become a guarantor; promising care in exchange for money or property then not providing this; and pressuring an older person to take out a loan which is not for their benefit.124 The NSW Government inquiry and ALRC inquiry viewed financial abuse of older people as “a widespread and increasing problem” with “inheritance impatience” often being a factor in such cases.125

In 2016–2017, the NSW Elder Abuse Helpline and Resource Unit received 1800 calls, 39% of which were related to financial abuse and 58% were related to psychological abuse, which often co-occurs with financial abuse.126

Section 49 of the Powers of Attorney Act 2003 (NSW) provides that it is an offence if an attorney acts after the principal has terminated the enduring power of attorney appointment. There is a maximum penalty of imprisonment of 5 years. However, this is of limited use in elder abuse situations, where the misuse usually occurs while the power is still in effect.

In some circumstances, offences such as fraud, deceptive conduct/obtain benefit by deception, stealing and other property-related offences are available to prosecute abuse of older people’s estates and finances.

Presumption of advancement

Coinciding with the increase in family accommodation agreements (such as granny flats or an agreement to allow a parent to reside in the premises with adult children), is an increase in instances of elder financial abuse in relation to family accommodation agreements.127

Such agreements are usually undocumented and, if they sour, may lead to disputes and litigation if the parent has made a financial contribution to the acquisition or improvement of property.

Such litigation usually involves the defendant seeking to rely on the presumption of advancement. The law presumes that, in certain circumstances, where person A has purchased property in the name of person B, they intended to make a gift to person B. To rebut the presumption, the purchaser must lead evidence of their actual intention which is inconsistent with the application of the presumption (ie evidence that, at the time of the purchase, the purchaser did not intend for the property to be a gift). The onus is on the purchaser to prove this evidence on the balance of probabilities. The evidence must relate to the purchaser’s intention at the time of the purchase. It will not be sufficient to show that the purchaser subsequently had a change of heart.

In Spink v Flourentzou128 the court held that the presumption of advancement should only arise where all the joint recipients of the money or property are in a relationship with the payer that is of a category that gives rise to the presumption: at [308]. In this case, the presumption did not arise because one of the recipients was the son-in-law. The court ordered that the plaintiff was entitled to the return of her contribution to the acquisition and renovation of the property, plus interest, secured by an equitable charge over the property: at [293].129

Capacity abuse

In NSW, the Office of the Legal Services Commission dealt with 35 “capacity complaints”130 (that is, lawyers failing to identify warning signs of potentially impaired capacity, acting when client capacity was clearly impaired, not seeking appropriate medical input on client decision-making capacity) between 2011 and 2015. By 2016, the number of capacity complaints was 1.2% of all written complaints received, rising from 0.4% in 2012.

Guardianship and financial management orders may be sought from the NSW Civil and Administrative Tribunal as a way of addressing financial abuse of an older person with capacity issues.

The demographic reality of an ageing population means that the likelihood of challenges to wills on the ground of testamentary capacity is increasing.131 Where there is doubt about a person’s capacity, the transaction is always in some danger of being attacked unless it can be shown that the action was a free will action of the elderly person.132 This is most readily demonstrated by the older person obtaining adequate, competent and relevant independent legal advice (well) prior to the impugned transaction.133

The Law Society of NSW publication “When a client’s mental capacity is in doubt: a practical guide for solicitors”134 provides some guidelines for solicitors to assist in the assessment of capacity when taking instructions. See also the Law Council of Australia’s “Best practice guide for legal practitioners on assessing mental capacity”.135

In Ryan v Dalton [2017] NSWSC 1007 at [107], the court made a number of observations for dealing with the “increasing number” of challenges to testamentary capacity. Justice Kunc, noting the ALRC recommendation 8-1,136 and bearing in mind matters such as elder abuse in probate matters, undue influence and testamentary capacity suggested:

It seems to me that the following is at least a starting point for dealing with this increasingly prevalent issue:

- 1.

The client should always be interviewed alone. If an interpreter is required, ideally the interpreter should not be a family member or proposed beneficiary.

- 2.

A solicitor should always consider capacity and the possibility of undue influence, if only to dismiss it in most cases.

- 3.

In all cases, instructions should be sought by non-leading questions such as: Who are your family members? What are your assets? To whom do you want to leave your assets? Why have you chosen to do it that way? The questions and answers should be carefully recorded in a file note.

- 4.

In case of anyone:

- (a)

over 70;

- (b)

being cared for by someone;

- (c)

who resides in a nursing home or similar facility; or

- (d)

about whom for any reason the solicitor might have concern about capacity;

the solicitor should ask the client and their carer or a care manager in the home or facility whether there is any reason to be concerned about capacity including as a result of any diagnosis, behaviour, medication or the like. Again, full file notes should be kept recording the information which the solicitor obtained, and from whom, in answer to such inquiries.

5. Where there is any doubt about a client’s capacity, then the process set out in sub-paragraph (3) above should be repeated when presenting the draft will to the client for execution. The practice of simply reading the provisions to a client and seeking his or her assent should be avoided.

The NSW Court of Appeal found that a solicitor should have ceased to act on being instructed by a wife attorney to transfer a farm in the sole name of her husband to her four daughters for $1.00 when the solicitor knew that (a) the husband had now lost capacity (b) the transaction was improvident (c) the transaction was inconsistent with the husband’s will which left the farm to his son and (d) he acted for both parties. Though the land had by now been registered in the daughters’ names, the court found that the equity could be traced with the result that the daughters were obliged to account for the loss to the now deceased husband’s estate.137

See further 11.5.1 — Legal capacity.

11.3 Older persons and crime

11.3.1 Prosecuting crimes committed against older persons

Generally speaking, Australian State and Territory laws do not provide specific offences against older persons. Although the Constitution contains certain heads of power which may provide a basis for the Commonwealth to legislate on matters for “ageing”, none specifically enables the Commonwealth to legislate or otherwise provide for protection against elder abuse.138 However, types of conduct which might be described as “elder abuse” are covered in all jurisdictions under offence provisions relating to personal violence and property offences. These include assault, sexual offences, kidnap and detain offences, intimidation and harassment, property and financial offences, fraud and theft offences.139 In its submission to the ALRC inquiry, the Law Council of Australia noted that “elder abuse” is rarely prosecuted under existing provisions.140 General neglect offences exist in all State and Territory jurisdictions141 although these are rarely utilised in respect of older people.142 Neglect is a Table 1 offence in NSW (ie indictable offence to be dealt with summarily) under s 44 of the Crimes Act if a person “who is under a legal duty to provide another person with the necessities of life and … who without reasonable excuse, intentionally or recklessly fails to provide that person with the necessities of life, is guilty of an offence if the failure causes a danger of death or causes serious injury”. The offence has a maximum penalty of five years and requires proof of a legal duty and causation. All State and Territory jurisdictions also have comprehensive family violence frameworks that provide for quasi-criminal, protective responses to abuse of older people in domestic settings.143

Under 21A(2)(h) of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW), the court is to take into account as an aggravating factor whether the offence was motivated by hatred for, or prejudice against, a group of people to which the offender believed the victim belonged (such as age, or having a particular disability), when determining the appropriate sentence for an offence.

11.3.2 Older persons as victims of crime

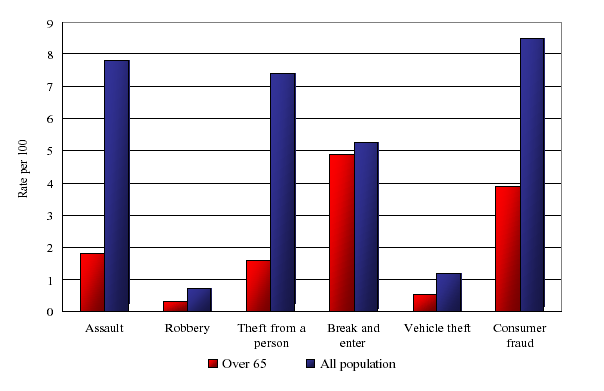

The victimisation rate for older Australians remains lower than the general population. This is due to their unique nature of social relationships and activities. Older people are victims of homicide most often as a result of an assault in their own home.144 Table 1 provides selected crime victimisation rates for people aged 65 years and over, compared with the total population.145

|

Often older Australians have more accumulated wealth which make them an attractive target for scammers. Common online scams targeting older people include dating site scams pretending to be prospective partners and investment, rebate and inheritance scams.146 Some crimes are specifically targeted at older people because of their perceived or actual vulnerability or because they are potentially easy to steal from. Offences under this heading include:

-

bogus worker cases where a person pretends that certain works require to be done to a property which are not required or where a person exaggerates the cost or value of any work which needs to be done

-

robberies

-

rogue traders

-

theft/doorstep theft

-

financial abuse — for example the illegal or unauthorised use of a person’s property, money, pension book or other savings

-

investment scams/fraudulent investment schemes, including where the internet is a vehicle for the crime. Older people are particularly susceptible to internet scams due to their lower digital confidence.147

-

A 2016 study found that vulnerability was related to the type of fraud invitation and that respondents aged 65 years and over were more likely to send money in response to a fraudulent invitation online than other age groups.148

Crimes against older people are often not reported. Research has found that many older people have little awareness of their legal rights and lack confidence in enforcing those rights. They can be reluctant to take legal action and find the law is disempowering and cannot solve their problems. Studies149 have identified the following as some of the possible reasons for under reporting:

- 1.

-

Reluctance to complain (the most common theme).150

- 2.

-

Lack of access to trusted people to tell of concerns or allegations; this may be a particular issue for older people who are socially isolated.

- 3.

-

Older people with mental health issues may find it especially difficult to report crime.

- 4.

-

Fear that the authorities will remove the victim from the abusive situation in the belief that it is the best course of action for the victim (as a consequence of which the victim may lose the home or be placed into an institution or care home which may be the exact outcome that the abuser was hoping for). See further Elder abuse at [11.2].

- 5.

-

Lack of access to telephone or other means of informing trusted people.

- 6.

-

Embarrassment, particularly if the abuser is a family member.

- 7.

-

When crimes against older people occur in a private home, there may be less chance that this comes to the attention of social care or other professionals.

- 8.

-

In cases of financial abuse, older people can be too embarrassed to report fraud if they have been duped into giving away money or valuable possessions.

- 9.

-

English is not the person’s first language. A person may lack confidence to come forward and might need the support of an independent interpreter, especially if a crime is committed by a family member or friend.

11.3.3 Older persons as witnesses in criminal proceedings

Generally, there is no reason that age impacts the capacity of a witness. A judicial officer can take steps to assist an elderly person who may have specific health and cognitive issues. See below at 11.5 — Practical considerations.

An older person may find the experience of cross-examination challenging or bewildering. Note that s 41 of the Evidence Act 1995 provides for the statutory control of improper cross-examination in both civil and criminal proceedings. Section 41 imposes an obligation on the court to disallow a “disallowable question” and is expressed in terms of a statutory duty whether or not objection is taken to a particular question (s 41(5)). The section specifically refers to the need to take account of the witness’s age and level of maturity and understanding (s 41(2)(a)). A judicial officer may control the manner and form of questioning of witnesses (ss 26 and 29(1)), and s 135(b) of the Evidence Act 1995 allows the court to exclude any evidence that might be misleading or confusing.

A line of cross-examination may be rejected by applying s 41: “Judges play an important role in protecting complainants from unnecessary, inappropriate and irrelevant questioning by or on behalf of an accused. That role is perfectly consistent with the requirements of a fair trial, which requirements do not involve treating the criminal justice system as if it were a forensic game in which every accused is entitled to some kind of sporting chance”.151

Vulnerable persons (including an older person with a cognitive impairment)152 in criminal proceedings or civil proceedings arising from the commission of a personal assault offence have a right to alternative arrangements for giving evidence when the accused is unrepresented. A vulnerable person who is a witness (other than the accused or defendant) must be examined in chief, cross-examined or re-examined by a person appointed by the court instead of by the accused or the defendant (s 306ZL).

See further [10-000] Evidence from vulnerable persons in Local Court Bench Book.

11.3.3.1 Older persons as witnesses in sexual assault matters

An older person who is a victim or is called as a witness in a sexual assault matter may lack access to information about what constitutes sexual assault. Given the most frequent perpetrators are family members, an older person may face barriers in reporting their experiences to others.153

Some points to consider include:

-

accessibility of the court for older people

-

ensuring provisions are made for those with a disability if required

-

cognitive impairment, short term memory loss combined with trauma can confuse a witness, particularly during cross-examination.

11.3.4 Older persons as perpetrators of crime

NSW has seen an overall increase in the prison population of 25% for the 10 years 2005-2015. Offenders aged over 55 increased on average 91% for this same period. This growth was most marked in the over 65 year olds, with elderly men increasing by approximately 225%.154

An ageing population increases the likelihood that older persons will be the perpetrators of crime. Offending rates for persons aged 50+ years have also increased since 2000. Older offenders increasingly contributed to all types of offences, with the most notable increases occurring among PCA/DUI offences, other traffic offences, drug offences and violent/sexual offences.155

Brain disease can contribute towards criminal behaviour.156 Some dementia patients have been found to have profound behavioural and psychological symptoms, and criminal manifestations in individuals with dementia have been reported in aged care facilities.157 Clinical interviews of 28 consecutive first-time offenders in a group of people aged over 65 years found a prevalence of dementia of 21%. There is a growing body of evidence that some people with dementia can show impaired moral judgments, decline in social interpersonal conduct, transgression in social norms and antisocial acts”. One study showed that some dementia patients committed sociopathic acts because of disinhibition, and others had sociopathic behaviour associated with agitation paranoia, rather than primarily from poor impulse control.158 A study in Sweden of 210 offenders aged 60 and over159 found that 7% had a diagnosis of dementia, 32% psychotic illness, 8% depressive or anxiety disorder, 15% substance abuse or dependence, and 20% personality disorder. Older offenders were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia or a personality disorder, and more likely to have dementia or an affective psychosis compared to younger ones. Typically older offenders with a diagnosis of dementia are charged with sexual offences.160

A NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) study161 found that between 2000 and 2015 there was a 94% increase in the proportion of older offenders (ie over 50) found guilty of a principal offence with a 228% increase in older Aboriginal offenders.162 Although older offenders are increasingly contributing to all offence types, the most notable increases over time in the proportion of older offenders were observed for drug offences (277%), other traffic offences (157%), PCA /DUI (90.2%) and violent/ sexual offences (81.5%). By 2015, nearly one in five PCA / DUI offenders were aged 50+ while around one in 10 persons found guilty of a traffic, violent, or drug offence were aged 50 years or more.163 The most common offence committed by an older person (over 50) was PCA/DUI, although the proportion of offenders in this category fell from 34% to 26% in the study period.164

The study found that the proportion of offenders aged 50 and over who received a custodial penalty rose by 111% between 2000 and 2015 with a 452% increase in the rate of older Aboriginal offenders.165 The most common offences for which older offenders were imprisoned in 2015 were violent/sexual offences (36.1%), drug offences (14.5%), justice procedure offences (13.8%) and property offences (13.0%).166 Possible reasons for why older people are appearing in court more often than in the past include older offenders being convicted of historical offences (mostly sexual offences as findings emerge from the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse) and older first time offenders with a decline in cognitive health.167

NSW has also observed an increase in Indigenous and female inmates among the aged population in this period. Although the actual numbers are small, aged females in custody have increased approximately 84% since 2005.168

Older offenders are increasingly presenting with a prior proven offence and/or have reoffended within two years of their index offence.169 The proportion of aged offenders in NSW with a history of prior imprisonment increased from 38.5% of the aged offender population in full-time custody in 1999 to 54.6% in 2009.170

Given the older prison population, and the fact that there is a 10-year differential between overall health of prisoners and that of the general population, older prisoners are more likely to experience premature ageing disease and disability, including dementia: see 11.1.4 — Health.

The study estimated that the number of older inmates in NSW custody is estimated to exceed 1,600 by 2020.171 The increasing proportion of older offenders in the prison population means that strategies will need to be put in place to cater for the specific requirements of older offenders, particularly Aboriginal offenders.172 Older inmates often have complex health issues and specific needs and vulnerabilities related to their age. Frail inmates have functional difficulties with the physical environment, including difficulties due to the number of steps, uneven surfaces, steep gradients and narrow doorways.173 There are few aged care beds available.174

Australia does not have specialist aged care providers for people who have committed serious criminal offences, and few private providers are keen to take them on. That leaves many older prisoners, particularly older sex offenders, in prison long after their earliest release date, which in turn leaves prison hospitals to operate as proxy aged care providers.175

11.4 Barriers

11.4.1 Access to justice

The Law and Justice Foundation conducted an extensive review of older people’s access to law.176 This highlighted both general barriers and particular barriers for older people in accessing legal services. The Law Council of Australia released their final report on the Justice Project in 2018.177 Examples of particular barriers are those relating to specific groups of older people, such as those living in residential aged care facilities and retirement villages; older people with specific health issues; those who have experienced abuse; those with difficulties with financial arrangements; and issues concerning older people with diminished capacity who require decision-making support.

Older people with a disability will require different levels of support in order to make their own decisions. This reflects the move toward supported decision-making principles that are part of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with a Disability,178 the recommendations of the ALRC Report on Equality, Capacity and Disability,179 and recent proposals to amend the NSW Guardianship Act 1987 to legislate for supported decision-making instead of substitute decision-making.180The NSW Government has enacted the Ageing and Disability Commissioner Act 2019 in response to a number of reports and inquiries, to assist in raising awareness of abuse, neglect and exploitation of older persons. This Act commenced on 1 July 2019.

The general barriers identified as impacting on an older person’s access to legal services included:

-

a lack of awareness of where to obtain legal information and assistance

-

a lack of appropriately communicated legal information

-

the high cost of legal services (financial barriers)

-

a lack of interest by some legal practitioners in older clients

-

potential conflict of interests when legal practitioners for older people are arranged by family members

-

difficulties in accessing legal aid, including restrictive eligibility tests

-

technological barriers, particularly for telephone and web-based services

-

a lack of availability of legal aid for civil dispute

-

lack of specialised legal services for older people, particularly in rural, regional and remote areas

-

lack of resources in community legal centres to tailor their services to the needs of older people.

See further Legal Aid NSW “Policy Bulletin 2019/12”, where the Legal Aid NSW Board approved changes to eligibility policies to clarify that legal aid is available to people who are experiencing, or are at risk of, elder abuse.181

Some of the specific issues impacting older people and their access to justice are set out below.

11.4.1.1 Disabilities, mobility and vulnerability

Some older persons may suffer from physical disabilities associated with ageing, such as deafness or a hearing impairment, blindness or a visual impairment, or fatigue or frailty.

Older people may require assistance in the form of a walker or walking stick. Courtroom facilities may be inaccessible (for example, stairs rather than lifts, narrow doors, no nearby parking, heavy doors) which make it difficult for them to participate.

Some older people may be unable to sit or stand in one position either at all or beyond a particular time or may become easily fatigued. Refer to Section 5 of this Bench Book for further information regarding practical considerations for people with disabilities.

11.4.1.2 Dementia

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia. As Alzheimer’s disease affects each area of the brain, certain functions or abilities are lost. Memory of recent events is the first to be affected, but as the disease progresses, long-term memory and other aspects of behaviour are affected.

Additional barriers may limit the ability of older people with Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias, to participate in the legal process. These include:

-

communication barriers: the language used may be too complex, fast or abstract, and/or the proceeding too lengthy. They may become easily distracted, very jumbled, severely distressed, anxious, frightened, aggressive or angry

-

fatigue

-

difficulty understanding or recalling dates, such as when events occurred, or appointments, such as court dates, and

-

as well as facing one or more of the above barriers, their communication barriers may be exacerbated by, for example, being unable to concentrate and/or process information easily, memory difficulties and/or by having disinhibited behaviour.

These barriers may be taken into consideration when the court is deciding whether or not to disallow a question in cross-examination: see s 41(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) and see further at 11.3.3 — Older persons as witnesses in criminal proceedings.

The vulnerable witness provisions may also apply to an older witness who is cognitively impaired: see Ch 6, Pt 6 of Criminal Procedure Act 1986 (NSW) and 11.5.1.1 — Competence of an older person to give evidence.

11.4.2 Digital exclusion

Older Australians are embracing the digital life. Seventy-nine per cent of older Australians have accessed the internet at some point in their lives.182Although the internet has the potential to assist older people with information needs, according to the Australian Digital Inclusion Index (ADII) 2017, Australians aged 65 years and over are the most digitally excluded age group.183 This is despite initiatives such as “Tech Savvy Seniors” digital literacy program, and the Tech Savvy Elders Roadshow, targeting older Aboriginal people, which provides free or low cost courses to seniors and was initiated in 2013. Aboriginal older people tend not to use institutional sources, even those set up for them by governments; rather they rely on social and family networks.184 The penetration of new technology among certain groups, especially older people from CALD backgrounds, Aboriginal older people and those in remote areas, still remains low.185 Further, the level of online engagement reduces in the older age cohorts.186

For some older persons, the shift to online services and communication has made it more difficult to find sources of legal information and access legal assistance.187 Further, effective internet searching is a complex skill.188 In submissions to the ALRC inquiry, it was noted that many government agencies require online form completion, which makes access (particularly for those in rural and remote areas) more difficult. Demographic differences reveal that within the older age group who are “offline”, they are more likely to be unemployed, have no tertiary education, have lower income, live outside major capital cities and be single/not married.189

Along with privacy concerns, older Australians frequently cite concerns about security and viruses as a reason for not accessing the internet.190 These are valid concerns as people over the age of 65 years are increasingly vulnerable to scams, particularly those involving the loss of money.191 In 2017 alone, there were almost 16,000 reports involving a loss of over $9 million to Scamwatch by people aged 65 years over.192

Vision decline, motor skill diminishment and cognition effects can also impair an older person’s ability to use a computer (although many government websites provide speech-enabled devices).

The lack of access to, and confidence with, information technology may be relevant where an older person is called for jury duty or appears as a witness or complainant in a trial, particularly in regional and remote areas.

11.4.3 Rural, regional and remote (RRR) issues

Lower population density and more geographically dispersed populations make it more difficult and expensive to create and maintain comprehensive service infrastructure such as transport, health care, social services, education, information and communications technology and culture, compared to urban areas. Consequently, rural populations have less access to services and activities and their situation may be further aggravated when combined with poorer socio-economic conditions. This puts rural populations at a disadvantage compared to urban ones and can be particularly problematic for older people who may face a greater risk of social isolation, reduced mobility, lack of support and health care deficits as a result of the place in which they live.193

Research consistently identifies the RRR population as having particular vulnerability to legal problems, a lack of capacity to resolve legal problems on their own and limited access to professional legal services. For older adults, legal problems can arise in matters that include:

the complexity of assets held by families resident in rural areas such as farming properties; lack of access to services that may assist with asset management arrangements and responses to situations where elder abuse is occurring or expended; and the dynamics involved in reporting or disclosing elder abuse in rural communities, where shame and concern to protect the family name potentially play an inhibiting role.194

Lawyer availability in some RRR areas varies and can impact a person’s access to justice. Some areas in NSW have no or few registered practising solicitors. Studies by the Law and Justice Foundation of NSW195 revealed that there were 19 local government areas (LGAs) in NSW without a single registered practising solicitor (private or public), and a number of other LGAs had only one or two. Access to solicitors in these outer regional, remote and very remote areas typically involved one or more parties travelling substantial distances. Further, the impacts on the justice system and rural communities of reduced levels of legal aid funding and increased demand for grants of legal aid are perceived as broad and adverse.

Limited access to transport together with mobility restrictions for some older people compound the barriers they face in seeking legal assistance.

The lack of access to legal advice is compounded by patchy, unreliable or absent mobile coverage in many rural and remote areas. Internet services, particularly in more isolated areas, only make available relatively small download allowances and these come at a much higher cost and slower speed than those services available in metropolitan areas.196 Data capped plans are common in non-urban areas, and would affect the capacity of those outside major capital cities to access some digital content.

Inadequate technological infrastructure in courts in RRR areas is a key contributing factor to RRR access to justice problems that must be addressed. The Law Council has suggested that the profession’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic offers an opportunity to build upon delivery of online courts, tribunals and dispute resolution forums, as well as to address issues faced by people experiencing disadvantage who may, for a variety of reasons, experience difficulties in adapting to legal services moving online — including members of RRR communities.197

Isolation also puts an older person at risk of neglect and financial exploitation: see, for example, NAD [2018] NSWCATGD 1 where an 84-year-old woman of Turkish heritage was being cared for by her son in regional NSW. Mrs NAD’s daughter initiated proceedings seeking the appointment of a guardian and financial manager for her mother, alleging the son was controlling, bullying and aggressive to the mother, neglected her and allowed no visitors to the home. A guardianship and financial management order was made in respect of Mrs NAD, as the tribunal found her interests were paramount.

In 2020, the Law Council of Australia (drawing upon the expertise of the Constituent Bodies, the Law Council’s RRR Committee, and the Justice Project Report) developed a RRR National Strategic Plan focusing on five key areas for action, with the corresponding projects to be implemented by the Law Council over 2021-23. The Law Council developed the strategies to address the main challenges faced by RRR lawyers and their communities, which include:

-

difficulties in recruiting and retaining lawyers, and ensuring succession plans

-

general shortages of lawyers in RRR areas

-

conflict of interest problems due to scarcity of locally available lawyers; and

-

scarce and over-stretched legal assistance services.

A copy of the National Strategic Plan can be found here.

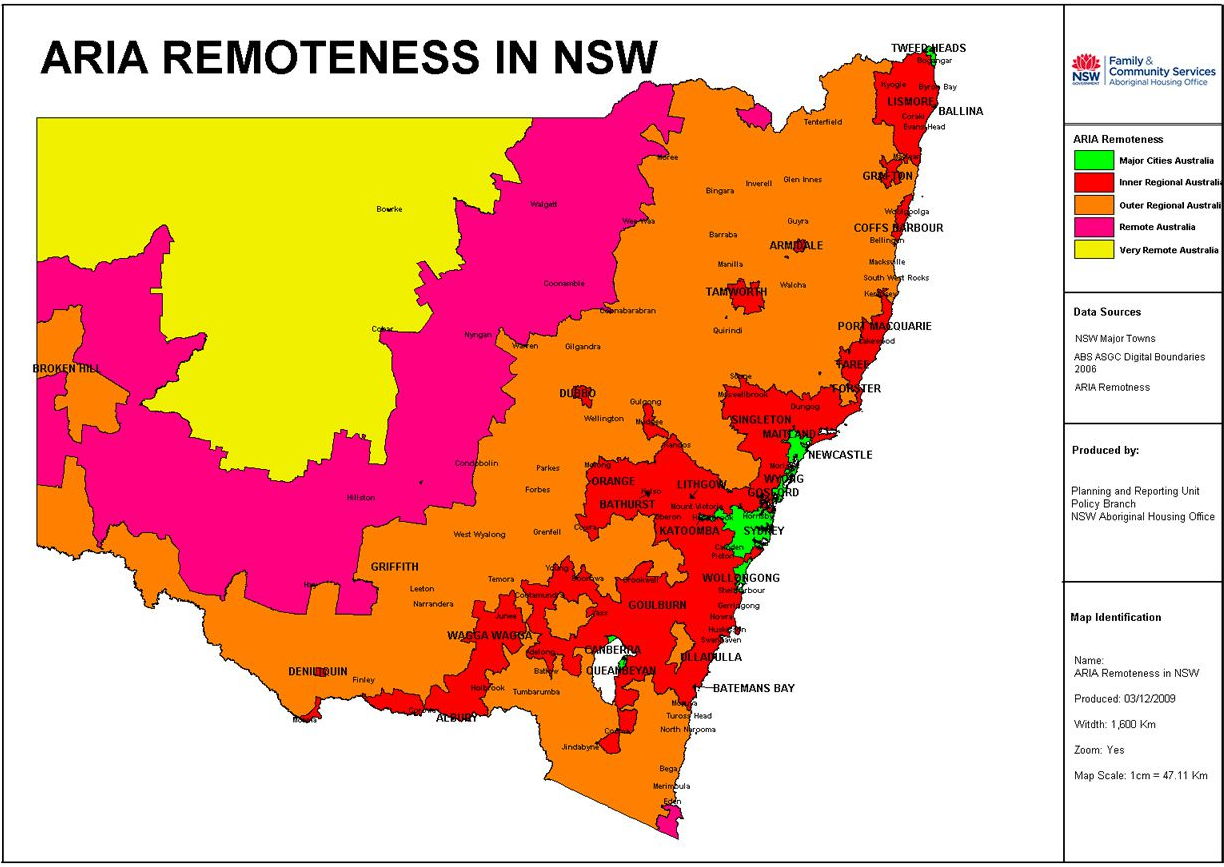

Figure 1 – Map of NSW showing areas of varying geographic remoteness198

11.5 Practical considerations

11.5.1 Legal capacity

Not all older clients will experience a cognitive impairment, however, dementia is the leading cause of disability in people aged 65 years and over.199

Capacity is the ability to make decisions. A presumption of capacity exists for all legal activities except the making of wills,200 but courts are reluctant to use a presumption as the foundation for a decision on an issue such as capacity and instead decide through close analysis of the facts of each case.201

Capacity is task or domain-specific, that is, peculiar to the particular type of decision made. Thus, the capacity task is different for entering into a contract; executing a power of attorney, will or deed; appointing an enduring guardian or an attorney under a power of attorney; or consenting to treatment, divorce or marriage.202

The degree of complexity of an older person’s affairs directly affects the level of cognitive function required to make a testamentary instrument. That is, the more complex the action, the more cognitive function is required.203 This represents an aspect of inherent vulnerability which greatly impacts legal capacity.204 A person’s inherent vulnerability may be exacerbated by situational factors, including family conflict. See further [11.2.3] — Succession/financial/capacity abuse.

The current NSW guidelines for capacity assessment caution lawyers about the potential for undue influence and the need to safeguard older people from abuse,205 however, family conflict is not raised separately as a factor that may influence decision-making capacity. See also the Law Council of Australia’s “Best practice guide for legal practitioners in relation to elder financial abuse” and its attachment “Best practice guide for legal practitioners on assessing mental capacity”206 which were developed in response to a recommendation in the Australian Law Reform Commission's report Elder abuse: a national legal response (2017).207 The best practice guides aim to assist legal practitioners to identify and respond to clients who may be subject to elder financial abuse and mitigate the risks of such abuse, and provide guidance on a legal practitioner’s obligations in relation to assessing a client’s mental capacity and how to assess capacity in various circumstances.

11.5.1.1 Competence of an older person to give evidence