Patrizia Poletti

Principal Research Officer (Statistics)

Introduction

As a result of “systemic leniency in sentencing” for the drink driving offence of high range prescribed concentration of alcohol (PCA), the NSW Attorney-General made an application to the Court of Criminal Appeal for a guideline judgment. A particular concern was that too many offenders were receiving s 10 orders — that is, orders that result in either an outright dismissal or a conditional discharge that avoids the usual consequences of a recorded conviction and sentence.1 On 8 September 2004, a five judge Bench2 of the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal delivered a guideline judgment for the offence.3

The guideline defines an “ordinary case” of a high range PCA offence and the circumstances in which certain dispositions may be appropriate or inappropriate.4 The guideline also identifies particular factors that increase the moral culpability of the offender and specifies what type of penalties may or may not be appropriate in such circumstances.5 The court decided not to make use of numerical indicators, such as are found in many earlier guideline judgments where penalty ranges are specified for particular types of offences.6

Aim of study

This study analyses the impact of the guideline on sentencing patterns for the offence of high range PCA before and after the guideline was delivered. Although the guideline applies to high range PCA offences, there may be a flow-on or incidental effect on sentencing patterns for similar offences, such as middle and low range PCA offences, and these are also considered. Further, this study examines results of sentence appeals to the District Court to ascertain whether there has been any noticeable shift in the nature and outcomes of appeals since the promulgation of the guideline.

Trends in the use of s 10 orders (2003–2004)

In order to gain an appreciation of developments that might have affected the relevant sentencing patterns, the trends in the penalties imposed for high range PCA offences over a two-year period were examined.

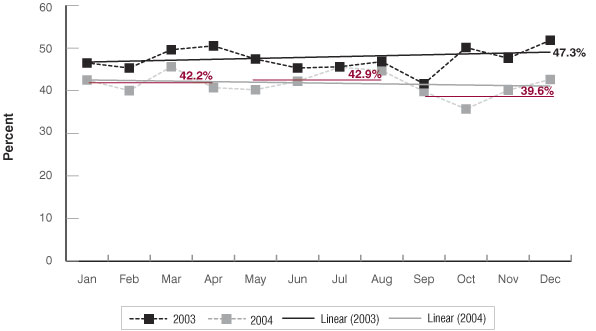

During the period prior to the promulgation of the guideline, much of the concern surrounding penalties imposed for high range PCA offences related to the excessive use of s 10 non-conviction orders (both dismissals and conditional discharges).7 Because mandatory licence disqualification can be avoided when a s 10 order is given, the corollary of this practice is an under use of licence disqualification. Figure 1 shows the trends in the use of s 10 non-conviction orders during 2003 and 2004.

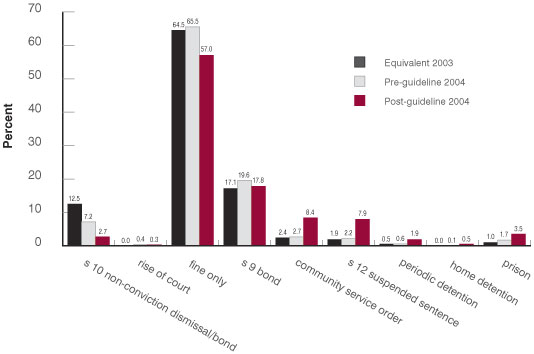

Figure 1. Trends in the use of s 10 non-conviction orders for high range PCA offences (2003–2004)

As Figure 1 shows, despite some fluctuation in the use of s 10 orders from one month to the next, a trend line applied to the sentencing data indicates a relatively constant use of s 10 orders in 2003, at around 10.4%. In 2004, however, the use of s 10 orders started to decline. They fell in January but soon rose again during February to April. More importantly, there was a significant fall in May and then another fall in September, with no further rises of any significance in subsequent months. In fact, when 2004 is divided into three equal periods — January to April, May to August and September to December, it is evident that the use of s 10 orders fell steadily from 9.3% to 5.9% and 2.2%, respectively.

At first glance, it appears that the guideline judgment (delivered in early September 2004), while also contributing to the fall in the use of s 10 orders, was not solely responsible for this decline, as this trend was apparent as early as May. A likely explanation is that the hearing date for the application of the guideline judgment also occurred in early May8 and it is possible that magistrates anticipated a forthcoming guideline relating to high range PCA offences and began to cut back on the use of s 10 orders.

Need for a guideline judgment

At the hearing, a range of material was placed before the Court of Criminal Appeal. Included were research studies9 and sentencing statistics10 that highlighted trends in the prevalence of the offence in NSW, described the kinds of penalties imposed on drink drivers and how frequently those penalties had been utilised in the Local Court. There was also material highlighting disparities in the use of s 10 orders across courts.

After closely considering submissions, the Court of Criminal Appeal found that there was evidence of inconsistency in the sentences handed down by the courts for high range PCA offences.11 It found that such offences were prevalent in NSW and commonly heard in the Local Court.12 The court recorded the high social and economic costs associated with the offence.13 Further, considering that high range PCA ranks amongst the most serious summary offences that can be dealt with in the Local Court, the Court of Criminal Appeal held that, contrary to the aims and intent of the legislation, the courts were not imposing adequate sentences,14 including licence disqualification periods,15 that reflected the objective seriousness of the offence. The court also found that sentences needed to deter other offenders from committing like crimes and that there was a need to denounce offenders for such conduct.16 Consequently, the issuing of a guideline judgment was justified.17

The guideline judgment

The guideline at [146] is expressed in the following terms:

“(1) An ordinary case of the offence of high range PCA is one where:

(i) the offender drove to avoid personal inconvenience or because the offender did not believe that he or she was sufficiently affected by alcohol;

(ii) the offender was detected by a random breath test;

(iii) the offender has prior good character;

(iv) the offender has nil, or a minor, traffic record;

(v) the offender’s licence was suspended on detection;

(vi) the offender pleaded guilty;

(vii) there is little or no risk of re-offending;

(viii) the offender would be significantly inconvenienced by loss of licence.

(2) In an ordinary case of an offence of high range PCA:

(i) an order under s 10 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act will rarely be appropriate;

(ii) a conviction cannot be avoided only because the offender has attended, or will attend, a driver’s education or awareness course;

(iii) the automatic disqualification period will be appropriate unless there is a good reason to reduce the period of disqualification:

(iv) a good reason under (iii) may include:

(a) the nature of the offender’s employment;

(b) the absence of any viable alternative transport;

(c) sickness or infirmity of the offender or another person.

(3) In an ordinary case of a second or subsequent high range PCA offence:

(i) an order under s 9 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act will rarely be appropriate;

(ii) an order under s 10 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act would very rarely be appropriate;

(iii) where the prior offence was a high range PCA, any sentence of less severity than a community service order would generally be inappropriate.

(4) The moral culpability of a high range PCA offender is increased by:

(i) the degree of intoxication above 0.15;

(ii) erratic or aggressive driving;

(iii) a collision between the vehicle and any other object;

(iv) competitive driving or showing off;

(v) the length of the journey at which others are exposed to risk;

(vi) the number of persons actually put at risk by the driving.

(5) In a case where the moral culpability of a high range PCA offender is increased:

(i) an order under s 9 or s 10 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act would very rarely be appropriate;

(ii) where a number of factors of aggravation are present to a significant degree, a sentence of any less severity than imprisonment of some kind, including a suspended sentence, would generally be inappropriate.

(6) In a case where the moral culpability of the offender of a second or subsequent high range PCA offence is increased:

(i) a sentence of any less severity than imprisonment of some kind would generally be inappropriate;

(ii) where any number of aggravating factors are present to a significant degree or where the prior offence is a high range PCA offence, a sentence of less severity than full-time imprisonment would generally be inappropriate.”

Methodology

The main focus of this study is to determine what impact, if any, the guideline judgment has had on sentencing patterns for high range PCA offences. Sufficient data has become available since the guideline was promulgated to undertake a comparative study of trends in sentencing for this offence. The analysis is based on first instance sentencing data provided by the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) and includes only the principal offence — that is, the offence attracting the most severe penalty in the group of offences for which an offender has been convicted.18

In order to measure the impact of the guidelines, this study compares the penalties imposed on high range PCA offenders in the period since the guideline was delivered — “post” (8 September 2004 to 31 December 2004) with the penalties imposed in a similar period before the guideline was delivered — “pre” (16 May 2004 to 7 September 2004). Figure 1 shows, however, that sentencing patterns began to change well before the guideline judgment was promulgated.

As already explained, the hearing date for the issuing of the guideline judgment took place shortly before the “pre” period, which also coincided with a significant change in sentencing patterns. It could be argued that measuring changes in sentencing patterns from only the “pre” period to the “post” period masks the whole impact of the guideline judgment which began to influence the pattern of sentences even before it was delivered by the court.

If that is the case, it would be inappropriate to limit the analysis to a simple pre and post-guideline comparison. Another comparison group — “equivalent 2003” (8 September 2003 to 31 December 2003) was chosen as a control group. Besides reflecting the same days and months covered in the “post” guideline period, this comparison group was chosen because the use of s 10 orders over that period was consistent with the rest of 2003, as shown by the trend line in Figure 1.19

Definitions and groupings

Thus, three comparison periods are used throughout this study:

- Equivalent 2003 (8 September 2003 to 31 December 2003).

- Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 September 2004).

- Post-guideline judgment (8 September 2004 to 31 December 2004).

The following analysis is based on offences prosecuted under s 9(4)(a) of the Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999 — driving a motor vehicle.20

Unfortunately, there was insufficient data to determine whether the high range PCA offence was an example of an ordinary case or one where the moral culpability of an offender was increased. Nevertheless, for the purposes of this study, it is assumed that the overall nature and quality of these offences did not significantly vary from one period to the next.

While it may not be possible to test precisely how the sentencing guideline was applied in each type of case, it is possible to compare differences in the penalties imposed in the case of a first offence of high range PCA with the case of a second or subsequent high range PCA offence. The Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999 distinguishes between the statutory maximum penalties applicable to a “first offence” and a “second or subsequent offence”.21

Clause 2 of the dictionary defines first offences and second or subsequent offences. If a person is prosecuted for a second or subsequent offence that entails having been “convicted” within five years of a “major offence”.22 The relevant legislation governing first offences and second or subsequent offences is contained in the Appendix.

The guideline considers the suitability or appropriateness of sentencing options. This study, therefore, compares the differences in the kinds of penalties imposed. Where appropriate, the length of licence disqualification periods are also analysed.

District Court Appeals

This study examines the nature and outcomes of all appeals to the District Court involving high range PCA offences that were heard during each of the three comparison periods. It should be noted that there was no easy way to link data from District Court appeals with first instance matters in the Local Court.23 It was possible, however, to manually trace first instance penalties for most of the appeals that were analysed.

The research questions

The analysis is divided into three main parts:

- The impact of the guideline.

- Appeals in the District Court.

- Whether the guideline had an incidental or flow-on effect on sentencing patterns for similar offences.

The first part examines the impact of the guideline judgment on the penalties imposed by the courts for high range PCA offences and addresses the following questions:

What impact has the guideline judgment had on:

- overall penalty types?

- the duration of licence disqualification periods?

- the use of s 10 non-conviction orders between the courts?

- penalties for second or subsequent offenders?

The second part examines the results of appeals to the District Court and addresses the following questions:

- What proportion of first instance sentences were appealed?

- How often were appeals to the District Court successful?

- What changes, if any, have there been in the general patterns of outcomes for successful appeals?

The third part examines the flow-on effect, particularly the sentencing patterns for middle range and low range PCA offences.

Results of the analysis

In the three periods covered by this study there were 4,148 cases where the principal offence was high range PCA under s 9(4)(a) of the Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999. In the post-guideline judgment period, there were 1,365 cases compared with 1,329 cases in the pre-guideline judgment period and 1,454 cases in the equivalent 2003 period.24

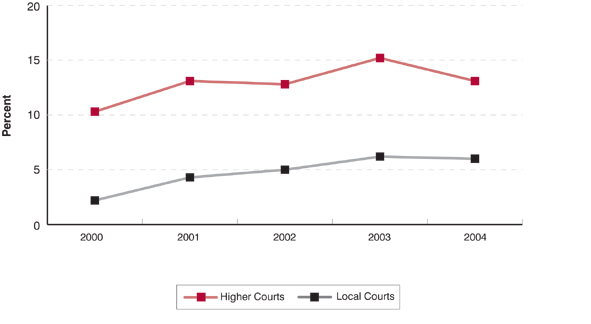

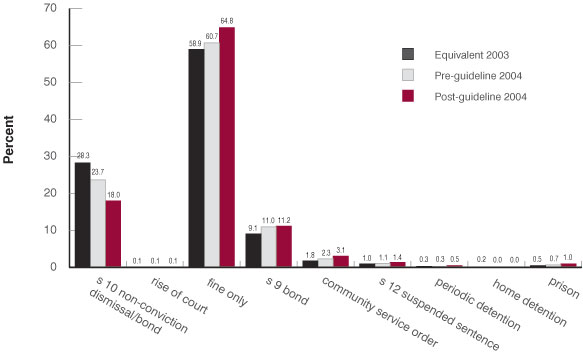

Overview of penalties

Figure 2 illustrates the types of penalties imposed for high range PCA offences for each comparison period. Clearly, it shows that there was a change in the pattern of sentencing in both the pre and post-guideline judgment periods. As mentioned, the use of s 10 non-conviction orders started falling in May 2004 — coinciding with the pre-guideline period. As Figure 2 shows, the use of s 10 orders fell from 10.3% in the equivalent 2003 period to 5.6% in the pre-guideline period. At the same time there was a small increase spread across most of the other dispositions, particularly s 9 good behaviour bonds (from 19.9% in the equivalent 2003 period to 22.6% in the pre-guideline period). There was a slight fall in the use of fines only.25

Figure 2. Trends in overall penalty types for high range PCA offences — Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Sep 2004 to 31 Dec 2004)

After the guideline judgment was delivered, however, there was a significant change in the pattern of sentencing for high range PCA offences. The use of s 10 orders further declined to just 2.2% in the post-guideline period. There was also a substantial fall in the use of penalties less severe than a community service order, particularly in the use of fines only (from 58.2% in the equivalent 2003 period to 57.3% in the pre-guideline period to 48.6% in the post-guideline period). These falls were offset by increases in the use of community service orders (from 4.4% to 5.4% to 10.5% respectively), s 12 suspended sentences (from 3.8% to 4.2% to 10.5%, respectively), periodic detention (from 1.0% to 1.3% to 2.9% respectively), home detention (from 0.1% to 0.4% to 0.7%, respectively) and full-time custody (from 2.2% to 2.9% to 6.0% respectively).

Licence disqualification periods

Licence disqualification is an essential component of the sentencing exercise for high range PCA. Parliament has stipulated four important statutory categories: for a first offence, a minimum of 12 months; for a second or subsequent offence, a minimum of three years; the automatic disqualification period for a first offence is three years; for a second or subsequent offence it is five years. Notwithstanding these statutory categories, it is common that the actual period of licence disqualification falls below the minimum or automatic level because the sentencer has taken account of the period of licence suspension prior to sentence. Licence suspension occurs from the date of the offence.

The guideline at [146](2)(iii) states that:

“in the ordinary case of an offence of high range PCA the automatic disqualification period will be appropriate unless there is a good reason to reduce the period of disqualification.”

Although the guideline did not contain an equivalent clause for a second or subsequent offence, it can be assumed that the same reasoning would apply.

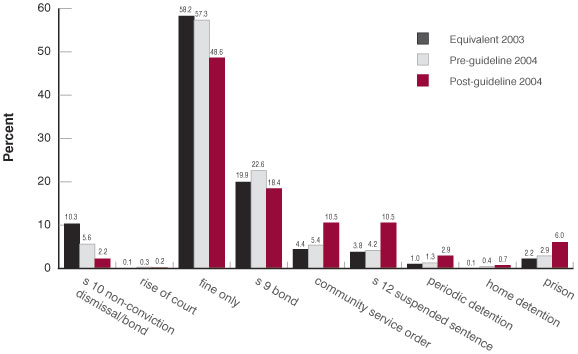

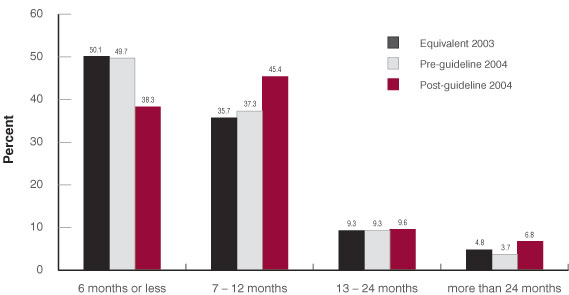

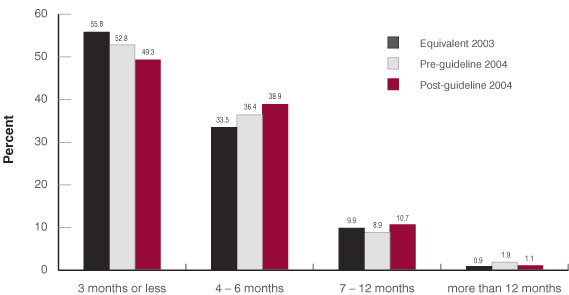

An immediate question is whether there are proportionately more licence disqualifications after the guideline. The decline in the use of s 10 non-conviction orders resulted in an increase in the proportion of high range PCA offenders who were disqualified from holding a driver’s licence (from 89.7% in the equivalent 2003 period to 94.4% in the pre-guideline period and 97.8% in the post-guideline period). Figure 3 shows the duration of licence disqualification periods imposed for high range PCA offences for each comparison period.

Figure 3. Trends in licence disqualification periods for high range PCA offences — Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Sep 2004 to 31 Dec 2004)a

a The disqualification periods imposed by the courts usually fell in the upper limit of each duration category — that is, 12 months, 18 months, 2 years, 3 years, 4 years and 5 years. The most common period longer than 5 years was 10 years.

While proportionately more high range PCA offenders were disqualified from driving, there clearly was little change in the duration of disqualification periods until after the guideline judgment was delivered. As Figure 3 illustrates, there was a significant increase in the length of disqualification periods in the post-guideline period. For example, licence disqualification periods of 12 months or less almost halved from 43.5% in the pre-guideline period to 23.1% in the post-guideline period. On the other hand, licence disqualification periods lasting longer than two years almost doubled from 22.1% in pre-guideline period to 41.6% in the post-guideline period. Most of the increase was due to the greater imposition of disqualification periods of three years from 13.4% in the pre-guideline period to 27.7% in the post-guideline period.

Interestingly, the proportion of offenders disqualified from driving for less than three years increased from 76.8% in the equivalent 2003 period to 79.8% in the pre-guideline period. This finding is understandable when one considers that proportionately more offenders were disqualified from driving in the pre-guideline period compared to the equivalent 2003 period. Those offenders who previously would have been given a s 10 order would most likely have received shorter disqualification periods than offenders who previously would not have been given the benefit of a s 10 order. Not until the guideline judgment was delivered were more substantial disqualification periods imposed.

The use of s 10 non-conviction orders and court location

Howie J said in the guideline judgment at [133]:

“there appears to me to be both generally and in some particular courts an over-utilisation of the section [10] in dealing with high range PCA offences, presumably in order to avoid the statutory consequences of a conviction. In my opinion, in the overwhelming majority of the 199 cases in the qualitative study where the offence was dismissed or the offender was discharged; there was no proper basis for the application of the section.”

As Figure 1 demonstrated, the use of s 10 orders has decreased. But part of the reason to issue a guideline judgment for high range PCA offences was the concern that some courts were imposing excessively lenient sentences. Material presented at the hearing showed that there was a strong relationship between the location of the sentencing court and the use of s 10 non-conviction orders.26 Table 1 shows the trends in the use of s 10 orders for high range PCA offences for each comparison period and the location of the court.27

Table 1. Trends in use of s 10 non-conviction orders for high range PCA offences by court location — Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Sep 2004 to 31 Dec 2004)

| Court Locations(a) | Equivalent 2003 | Pre-guideline 2004 | Post-guideline 2004 | ||||||

| N | n | % | N | n | % | N | n | % | |

| Sydney | 705 | 40 | 5.7 | 696 | 23 | 3.3 | 652 | 6 | 0.9 |

| Inner Sydney | 59 | 3 | 5.1 | 59 | 2 | 3.4 | 53 | 1 | 1.9 |

| Eastern Sydney | 57 | 1 | 1.8 | 66 | 2 | 3.0 | 53 | 0 | 0.0 |

| St George – Sutherland | 71 | 2 | 2.8 | 57 | 1 | 1.8 | 71 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Canterbury – Bankstown | 24 | 2 | 8.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Fairfield – Liverpool | 80 | 2 | 2.5 | 71 | 4 | 5.6 | 65 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Outer South Western Sydney | 39 | 3 | 7.7 | 33 | 2 | 6.1 | 38 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Inner Western Sydney | 36 | 1 | 2.8 | 82 | 1 | 1.2 | 59 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Central Western Sydney | 34 | 0 | 0.0 | 41 | 0 | 0.0 | 34 | 2 | 5.9 |

| Outer Western Sydney | 74 | 2 | 2.7 | 87 | 0 | 0.0 | 90 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Blacktown | 30 | 1 | 3.3 | 35 | 0 | 0.0 | 27 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Lower Northern Sydney | 34 | 3 | 8.8 | 32 | 3 | 9.4 | 33 | 1 | 3.0 |

| Central Northern Sydney | 33 | 1 | 3.0 | 20 | 1 | 5.0 | 24 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Northern Beaches | 51 | 1 | 2.0 | 44 | 0 | 0.0 | 34 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Gosford – Wyong | 83 | 18 | 21.7 | 69 | 7 | 10.1 | 71 | 2 | 2.8 |

| Outside Sydney | 749 | 110 | 14.7 | 633 | 52 | 8.2 | 713 | 24 | 3.4 |

| Hunter | 173 | 47 | 27.2 | 114 | 15 | 13.2 | 155 | 7 | 4.5 |

| Illawarra | 75 | 3 | 4.0 | 101 | 2 | 2.0 | 91 | 4 | 4.4 |

| Richmond – Tweed | 120 | 16 | 13.3 | 89 | 7 | 7.9 | 73 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Mid-North Coast | 92 | 9 | 9.8 | 84 | 4 | 4.8 | 93 | 3 | 3.2 |

| Northern | 49 | 7 | 14.3 | 42 | 6 | 14.3 | 52 | 0 | 0.0 |

| North Western | 37 | 6 | 16.2 | 28 | 1 | 3.6 | 36 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Central West | 47 | 7 | 14.9 | 57 | 5 | 8.8 | 47 | 0 | 0.0 |

| South Eastern | 62 | 7 | 11.3 | 60 | 2 | 3.3 | 74 | 4 | 5.4 |

| Murrumbidgee | 47 | 3 | 6.4 | 31 | 4 | 12.9 | 37 | 2 | 5.4 |

| Murray | 36 | 3 | 8.3 | 20 | 3 | 15.0 | 43 | 2 | 4.7 |

| Far West | 11 | 2 | 18.2 | 7 | 3 | 42.9 | 12 | 1 | 8.3 |

| Total | 1454 | 150 | 10.3 | 1329 | 75 | 5.6 | 1365 | 30 | 2.2 |

(a) ABS statistical divisions(SD) include Sydney and the 11 locations outside Sydney. The 14 locations within Sydney are known as ABS statistical subdivisions (SSD).

N refers to the total number of cases.

n refers to the number of cases given a s 10 non-conviction order.

% refers to the proportion of cases given a s 10 noon-conviction order.

It is certainly evident, that the majority of courts have reduced their use of s 10 orders for high range PCA offences. Out of the 14 statistical subdivisions within Sydney, only one (Central Western Sydney) recorded a higher use of s 10 orders after the guideline judgment was delivered. Of the 12 statistical divisions in NSW, only one (Illawarra) used s 10 orders slightly more often in the post-guideline period. It should be noted, however, that only a very small number of s 10 orders were imposed — especially in the post-guideline period — and, in all likelihood, were for cases with most exceptional circumstances.

Also evident was the number of courts that had not imposed a s 10 order in the post-guideline period. For example, in the equivalent 2003 period, only one location within Sydney (Central Western Sydney) and none outside of Sydney had not imposed a s 10 order. In the pre-guideline period, four locations within Sydney had not imposed a s 10 order. In the post-guideline period, however, nine locations within Sydney and three locations outside of Sydney had not imposed a s 10 order.

In Sydney courts, the use of s 10 orders fell from 5.7% in the equivalent 2003 period to 3.3% in the pre-guideline period to 0.9% in the post-guideline period. Within Sydney, the largest reduction in the use of s 10 orders occurred in the Gosford–Wyong region (from 21.7% in the equivalent 2003 period to 10.1% in the pre-guideline period and 2.8% in the post-guideline period). The use of s 10 orders in courts located outside Sydney also declined (from 14.7% in the equivalent 2003 period to 8.2% in the pre-guideline period to 3.4% in the post-guideline period). Courts in the Hunter region accounted for the largest falls outside Sydney (from 27.2% in the equivalent 2003 period to 13.2% in the pre-guideline period and 4.5% in the post-guideline period).

Generally speaking, the use of s 10 orders was always higher for courts located outside Sydney. At [146] (2)(iii) and (iv)(b) of the guideline judgment — in the ordinary case of a first high range PCA offender — the court states that a good reason to reduce the automatic period of disqualification may include the absence of any viable alternative transport. The absence of viable transport in many NSW country and regional areas may also explain the higher use of s 10 non-conviction orders in courts located outside Sydney.

Licence disqualification periods

An analysis of the licence disqualification periods imposed on high range PCA offenders revealed that courts located outside Sydney were more likely than Sydney courts to impose disqualification periods shorter than 3 years. This was the case for each comparison period (78.7% compared with 75.0% in the equivalent 2003 period, 83.0% compared with 77.1% in the pre-guideline period and 63.4% compared with 58.4% in the post-guideline period). As mentioned earlier, licence disqualification periods got longer after the guideline judgment was delivered. This was true whether the sentencing court was situated in Sydney or outside Sydney.

Second or subsequent offenders

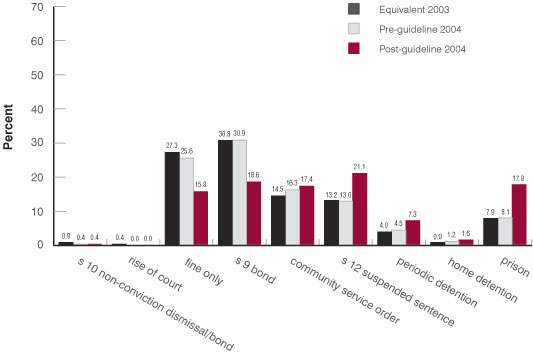

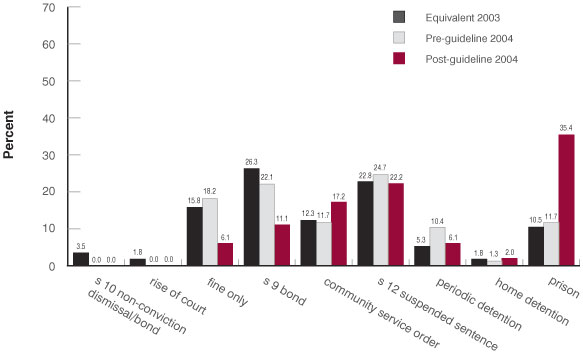

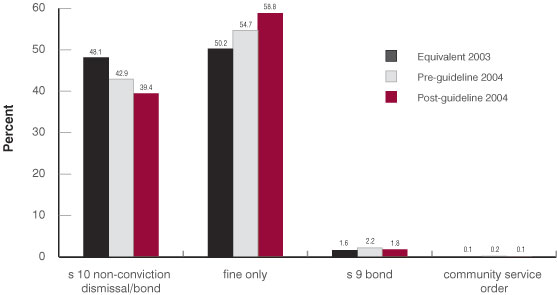

The guideline judgment differentiates between sentencing options that should apply to first offenders and second or subsequent offenders in both the ordinary case and where the moral culpability of the offender has increased. Figure 4 shows the trends in the types of penalties imposed for each comparison period in the case of a first high range PCA offence. Figure 5 presents the same information in the case of a second or subsequent high range PCA offence.

Figure 4. Trends in overall penalty types imposed for high range PCA offences — first offence — Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Sep 2004 to 31 Dec 2004)

Figure 5. Trends in overall penalty types imposed for high range PCA offences — second or subsequent offence — Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Sep 2004 to 31 Dec 2004)

Figure 5. Trends in overall penalty types imposed for high range PCA offences — second or subsequent offence — Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Sep 2004 to 31 Dec 2004)

Looking at both figures it was clearly apparent that, regardless of the time period selected, second or subsequent high range PCA offenders received harsher sentences and very few were given a s 10 non-conviction order. Second or subsequent offenders were less likely than first high range PCA offenders to receive fines only and more likely to receive other dispositions higher up the sentencing hierarchy.

Moreover, the figures show the impact of the guideline judgment on the sentencing patterns for both first and subsequent offenders. Since the majority of high range PCA offenders in this study were first offenders, the sentencing patterns were very similar to those already described in the overview. The differences relate only to the magnitude of the decline in the use of s 10 orders (from 12.5% in the equivalent 2003 period to 7.2% in the pre-guideline period to 2.7% in the post-guideline period) and fines only (from 64.5% in the equivalent 2003 period to 65.5% in the pre-guideline period to 57.0% in the post-guideline period) and the magnitude of the increase in the use of other dispositions, especially community service orders (from 2.4% in the equivalent 2003 period to 2.7% in the pre-guideline period to 8.4% in the post-guideline period) and s 12 suspended sentences (from 1.9% in the equivalent 2003 period to 2.2% in the pre-guideline period to 7.9% in the post-guideline period).

In the case of second or subsequent high range PCA offenders, however, there was a substantial reduction in the use of fines only (from 27.3% in the equivalent 2003 period to 25.6% in the pre-guideline period to 15.8% in the post-guideline period) and s 9 bonds (from 30.8% in the equivalent 2003 period to 30.9% in the pre-guideline period to 18.6% in the post-guideline period). These falls were offset by increases in the use of more severe penalties, especially full-time imprisonment (from 7.9% in the equivalent 2003 period to 8.1% in the pre-guideline period to 17.8% in the post-guideline period), s 12 suspended sentences (from 13.2% in the equivalent 2003 period to 13.0% in the pre-guideline period to 21.1% in the post-guideline period) and periodic detention (from 4.0% in the equivalent 2003 period to 4.5% in the pre-guideline period to 7.3% in the post-guideline period).

The guideline, however, at [146] (3)(iii) and 6(ii), also distinguishes between sentences for second or subsequent offenders where the prior offence was a high range PCA offence. Figure 6 shows the trends in the types of penalties imposed for such offenders for each comparison period.

Figure 6 shows that, since the guideline judgment was delivered, subsequent high range PCA offenders where the prior offence was high range PCA have received harsher sentences. For example, the use of penalties less severe than a community service order have significantly decreased (from 47.4% in the equivalent 2003 period and 40.3% in the pre-guideline period to just 17.2% in the post-guideline period). Alternatively, there has been a trebling in the proportion of such offenders sentenced to full-time imprisonment (from 10.5% in the equivalent 2003 period and 11.7% in the pre-guideline period to 35.4% in the post-guideline period).

Figure 6. Trends in overall penalty types imposed for high range PCA offences — prior high range PCA offence —Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Se 2004 to 31 Dec 2004)

Licence disqualification periods

As already mentioned, different minimum and automatic disqualification periods apply to first offenders (12 months and three years respectively) and second or subsequent offenders (three years and five years respectively).

An analysis of the licence disqualification periods imposed on first and second or subsequent high range PCA offenders revealed, unsurprisingly, that second or subsequent offenders were more likely than first offenders to receive longer disqualification periods, regardless of the time period.

More importantly, however, the analysis also revealed that longer disqualification periods were imposed after the guideline was delivered. For example, the median disqualification period imposed in both the equivalent 2003 period and the pre-guideline period was 12 months for first offenders and three years for second or subsequent offenders. In the post-guideline period, however, the median disqualification period imposed on first offenders was twice as long (two years). While the median disqualification period imposed on second or subsequent offenders was unchanged (three years), proportionately fewer offenders received periods of three years or less in the post-guideline period (56.1% compared with 75.5% in the pre-guideline period and 74.2% in the equivalent 2003 period).

In the case of second or subsequent offenders where the prior offence was high range PCA, the median disqualification period imposed increased from three years in the equivalent 2003 period and the pre-guideline period to four years in the post-guideline period.

Appeals to the District Court

The District Court, in its appellate jurisdiction, plays an important role in sentencing for summary offences. The appeals are conducted as rehearings of the evidence although fresh evidence may be given.28 In Budget Nursery v Commissioner of Taxation,29 Hunt J (as he then was), explained the appeal jurisdiction in the following terms:

“It is certainly inappropriate for the judge to consider only whether he should either reduce or increase the penalty imposed by the magistrate; it is also inappropriate to consider only whether he should interfere with that penalty. He must in every case proceed to consider for himself in the exercise of his own discretion what penalty should be imposed. That is not to say that he cannot agree with what the magistrate has done, but he may do so only if such penalty imposed by the magistrate accords with his own independent assessment of the circumstances of the case.”

Rate of Appeal

The proportion of first instance sentences for high range PCA offences that were appealed to the District Court was estimated30 to be 5.4% in the equivalent 2003 period. In the pre-guideline period, the proportion that appealed increased to 7.4% and was 6.7% in the post-guideline period. Defendants appealing against the severity of their sentence accounted for the vast majority of appeals to the District Court. There was only a small number of Crown appeals (only 7 cases) and for the purposes of this study they had very little statistical value.

In absolute terms the number of severity appeals increased from 84 in the equivalent 2003 period to 100 in the pre-guideline period and 94 in the post-guideline period and as a percentage of first instance cases from 5.3% to 6.9% and 6.5%, respectively. Table 2 portrays the nature and outcome of all appeals to the District Court for high range PCA offences for each comparison period.

Table 2. Nature and outcome of appeals to the District Court for high range PCA offences — Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Sep 2004 to 31 Dec 2004)

| Equivalent 2003 | Pre-guideline 2004 | Post-guideline 2004 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Severity appeals | 84 | 100 | 94 | |||

| Successful outcome | 68 | 81.0 | 77 | 77.0 | 76 | 80.9 |

| Sentence varied | ||||||

| penalty type only | 20 | 29.4 | 22 | 28.6 | 19 | 25.0 |

| penalty length only | 9 | 13.2 | 13 | 16.9 | 13 | 17.1 |

| disqualification period only | 16 | 23.5 | 20 | 26.0 | 20 | 26.3 |

| penalty type & disqualification period | 16 | 23.5 | 18 | 23.4 | 13 | 17.1 |

| penalty length & disqualification period | 7 | 10.3 | 4 | 5.2 | 11 | 14.5 |

| DPP appeals | 1 | 5 | 1 | |||

| Successful outcome | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 100.0 |

| Sentence varied | ||||||

| penalty type & disqualification period | 1 | 100.0 | ||||

| Conviction appeals(a) | 6 | 5 | 4 | |||

| Successful outcome | 1 | 16.7 | 1 | 20.0 | 1 | 25.0 |

(a) Offenders who appealed against their conviction also appealed against the severity of sentence. As such, cases where the conviction appeal was unsuccessful have also been included in severity appeals.

Severity appeals

There was a high success rate for severity appeals. Around 80% of severity appeals were successful and there was little difference in the success rate observed for each period (81.0% in the equivalent 2003 period compared with 77.0% in the pre-guideline period and 80.9% in the post-guideline period). The study analysed whether the guideline influenced re-sentencing. The general pattern of outcomes for successful severity appeals changed after the guideline judgment was delivered. For example, in the post-guideline period, District Court judges were less likely to vary the type of penalty imposed by the Local Court (42.1% compared to 52.9% in the equivalent 2003 period and 51.9% in the pre-guideline period). Instead, judges were more likely to vary the amount or duration of the penalty imposed at first instance (31.6% compared with 23.5% in the equivalent 2003 period and 22.1% in the pre-guideline period).

In approximately one-quarter of severity appeals, only the licence disqualification period was varied (23.5% in the equivalent 2003 period, 26.0% in the pre-guideline period and 26.3% in the post-guideline period). Including defendants who had their disqualification period varied as well as their primary penalty, over one-half of defendants who appealed were successful in having their disqualification period varied (57.4% in the equivalent 2003 period, 54.5% in the pre-guideline period and 57.9% in the post-guideline period).

Severity appeals where imprisonment was imposed

As shown in Table 3, similar patterns were found in the outcomes for successful appeals by defendants who were sentenced to full-time imprisonment for high range PCA offences. In absolute terms the number of severity appeals against a term of imprisonment increased from 26 in the equivalent 2003 period to 35 in the pre-guideline period and 32 in the post-guideline period.Approximately one-third of severity appeals were against a term of imprisonment (31.0% in the equivalent 2003 period, 35.0% in pre-guideline period and 34.0% in the post-guideline period).

Like the overall pattern, sentence severity appeals against imprisonment were also likely to succeed. Unlike the overall pattern, however, they were more likely to succeed in the period after the guideline judgment was delivered (96.9% compared with 80.8% in the equivalent 2003 period and 80.0% in pre-guideline period). The corollary is that appeals against sentences less severe than full-time imprisonment were less likely to succeed in the post-guideline period (72.6% compared with 81.0% in the equivalent 2003 period and 75.4% in the pre-guideline period).

Further, the general pattern of outcomes for successful severity appeals against full-time imprisonment changed after the guideline judgment was delivered. For example, in the post-guideline period, District Court judges were less likely to vary the penalty of imprisonment imposed by the Local Court (41.9% compared to 57.1% in the equivalent 2003 period and 64.3% in the pre-guideline period). Alternatively, judges were more likely to vary the term of imprisonment imposed at first instance (51.6% compared with 38.1% in the equivalent 2003 period and 32.1% in the pre-guideline period).

In a small number of cases, only the licence disqualification period was varied (4.8% in the equivalent 2003 period, 3.6% in the pre-guideline period and 6.5% in the post-guideline period). Including defendants who had their disqualification period varied as well as their term of imprisonment, revealed that these defendants were more likely to have their disqualification period varied if they appealed in the post-guideline period (29.0% compared to 14.3% in the equivalent 2003 period and 17.9% in the pre-guideline period). This finding is understandable when one considers that disqualification periods imposed by the Local Court take into account the time to be served in custody.

Table 3. Outcome of severity appeals to the District Court for high range PCA offences — prison — Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Sep 2004 to 31 Dec 2004)

| Equivalent 2003 | Pre-guideline 2004 | Post-guideline 2004 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Severity appeals — prison | 26 | 35 | 32 | |||

| Successful outcome | 21 | 80.8 | 28 | 80.0 | 31 | 96.9 |

| Sentence varied | ||||||

| penalty type only | 11 | 52.4 | 15 | 53.6 | 12 | 38.7 |

| penalty length only | 7 | 33.3 | 8 | 28.6 | 10 | 32.3 |

| disqualification period only | 1 | 4.8 | 1 | 3.6 | 2 | 6.5 |

| penalty type & disqualification period | 1 | 4.8 | 3 | 10.7 | 1 | 3.2 |

| penalty length & disqualification period | 1 | 4.8 | 1 | 3.6 | 6 | 19.4 |

Flow-on effect to other PCA offences

While the guideline judgment applies only to high range PCA offences, a question arises as to whether it has had a flow-on effect to other PCA offences, particularly middle range and low range PCA offences.

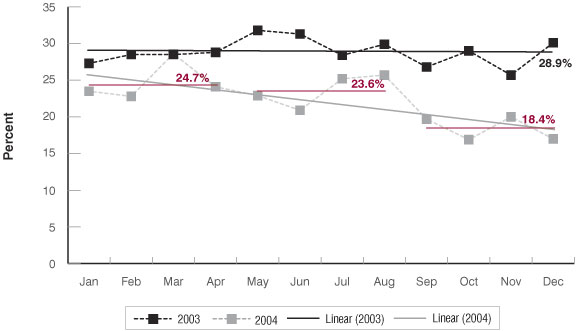

In order to attribute changes in sentencing patterns for other PCA offences to the guideline judgment relating to high range PCA offences, it is important to consider sentencing patterns prior to the guideline judgment. As was the case with high range PCA, the use of s 10 non-conviction orders was used to describe any variations in the overall sentencing pattern for middle range PCA (Figure 7) and low range PCA (Figure 8) offences. Both types of offences received a greater proportion of s 10 orders than high range PCA offences.

Figure 7. Trends in the use of s 10 non-conviction orders for middle range PCA offences (2003–2004)

Figure 8. Trends in the use of s 10 non-conviction orders for low range PCA offences (2003–2004)

These figures show a different pattern to that observed for high range PCA (see Figure 1). The main difference relates to when the use of s 10 orders began to decline. In the case of high range PCA, the use of s 10 orders began to fall in May 2004 coinciding with the pre-guideline period. In the case of middle range PCA and low range PCA, however, the decline in the use of s 10 orders began several months earlier. As was the case for high range PCA, the proportion of s 10 orders imposed for middle range PCA and low range PCA offences was fairly steady during 2003 (averaging 28.9% and 47.3%, respectively). Dividing 2004 into three equal periods, however, revealed that the use of s 10 orders declined substantially during January to April (to 24.7% and 42.2%, respectively). There was little change in the use of s 10 orders during May to August (23.6% and 42.9%, respectively), although there was another noticeable fall in the use of s 10 orders during September to December (to 18.4% and 39.6%, respectively).

The following events may partly explain the differences observed. The first relates to an inquiry, late in 2003, by the Chief Magistrate seeking information from all NSW magistrates regarding the use of s 10 non-conviction orders. This followed an invitation to comment on a proposed report by BOCSAR emphasising the disparity and increase in the use of s 10 orders for PCA offences.31 The inquiry not only drew attention to the use of s 10 orders it also drew attention to the Crown Advocate’s submission to the Court of Criminal Appeal for a guideline judgment on appropriate levels of sentencing for PCA offences. The second relates to a number of metropolitan and regional conferences organised by the Judicial Commission during February, March and April 2004 where the use of s 10 orders was discussed among magistrates and where all NSW magistrates were in attendance.

These events appear to have had the effect of reducing the overall use of s 10 non-conviction orders preceding the guideline judgment, particularly in relation to middle range and low range PCA offences.

Another important difference in the use of s 10 orders between high range PCA offences and other PCA offences relates to the pattern observed in the pre-guideline judgment period. In the case of high range PCA, the use of s 10 orders fell dramatically in the period from May to August, whereas little difference was observed in the same period for middle range and low range PCA offences.

Nevertheless, there was a significant decline in the use of s 10 orders for all three categories of PCA offences in the period September to December, following the promulgation of the guideline judgment relating to high range PCA offences.

Figures 9 and 10 show the types of penalties imposed for middle range PCA and low range PCA offences, respectively. Since there was little difference in the use of s 10 orders in the period from January to April and May to August, it was decided to use the same comparison periods used for high range PCA offences.32

Figure 9. Trends in overall penalty types imposed for middle range PCA offences — Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Sep 2004 to 31 Dec 2004)

Figure 10. Trends in overall penalty types imposed for low range PCA offences — Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Sep 2004 to 31 Dec 2004)

Figure 10. Trends in overall penalty types imposed for low range PCA offences — Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Sep 2004 to 31 Dec 2004)

As mentioned above, the use of s 10 non-conviction orders for both middle range and low range PCA offences started falling prior to the guideline judgment being promulgated. In the case of middle range PCA offences, the decline in the use of s 10 orders was offset by small increases in the use of other dispositions such as fines only, s 9 bonds and community service orders. In the case of low range PCA offences, most of the reduction in the use of s 10 orders was accompanied by an increase in the use of fines only. After the guideline judgment was delivered, there was a further reduction in the use of s 10 orders and an increase in the use of more severe penalties.

Licence disqualification periods

Figures 11 and 12 show the duration of licence disqualification periods imposed for middle range PCA and low range PCA offences, respectively.

In the case of middle range PCA offences, the length of disqualification periods did not significantly increase until after the guideline judgment for high range PCA offences was delivered. Most of the increase was due to the greater use of the automatic disqualification period (12 months). In the case of low range PCA offences, there was already a trend towards imposing longer disqualification periods reflecting the automatic disqualification period (6 months) in the pre-guideline period, which was further reinforced after the guideline judgment was delivered.

Figure 11. Trends in licence disqualification periods for middle range PCA offences — Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Sep 2004 to 31 Dec 2004) a

(a) The disqualification periods imposed by the courts usually fell in the upper limit of each duration category — that is, 6 months, 12 months and 2 years. The most common period longer than 2 years was 3 years.

Figure 12. Trends in licence disqualification periods for low range PCA offences — Equivalent 2003 (8 Sep 2003 to 31 Dec 2004), Pre-guideline judgment (16 May 2004 to 7 Sep 2004) and Post-guideline judgment (8 Sep 2004 to 31 Dec 2004)a

(a) The disqualification periods imposed by the courts usually fell in the upper limit of each duration category — that is, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months.

Statutory minimum and automatic disqualification periods also differ for first offenders and second or subsequent offenders sentenced for middle range and low range PCA. The minimum and automatic disqualification periods for a first middle range PCA offence are 6 months and 12 months, respectively. In the case of a second or subsequent middle range PCA offence, the minimum and automatic disqualification periods are 12 months and three years, respectively.

The median disqualification period in the case of a first middle range PCA offence was six months in both the equivalent 2003 period and in the pre-guideline period. After the guideline, however, the median disqualification period increased to eight months. A similar pattern was found in the case of a second or subsequent middle range PCA offence where the median disqualification period imposed after the guideline was two years, compared with 18 months in the equivalent 2003 period and the pre-guideline period.

The minimum and automatic disqualification periods for a first low range PCA offence are three months and six months, respectively, and for a second or subsequent offence, they are six months and 12 months, respectively.

The median disqualification period in the case of a first low range PCA offence was three months in both the equivalent 2003 period and in the pre-guideline period. While the median disqualification period imposed after the guideline was also three months, proportionately fewer first offenders received periods of three months or less (58.4% compared with 63.7% in the pre-guideline period and 67.1% in the equivalent 2003 period). The median disqualification period in the case of a second or subsequent low range PCA offence was six months in both the equivalent and pre-guideline period. The median disqualification period increased to nine months following the promulgation of the guideline judgment.

Conclusions

The guideline, together with the research and educational programs leading up to it, has had the following impact:

Sentences for high range PCA offences have increased in severity with:

- A dramatic reduction in the use of s 10 non-conviction orders, even though over the 12 month period it was reducing in steps. The use of s 10 orders fell from 10.3% in the equivalent 2003 period to 5.6% in the pre-guideline period to just 2.2% in the post-guideline period.

- A corresponding increase in the proportion of offenders disqualified from driving, from 89.7% in the equivalent 2003 period to 94.4% in the pre-guideline period to 97.8% in the post-guideline period.

- Longer disqualification periods — proportionately more offenders received the automatic rather than the minimum disqualification period.

In addition, there has been more consistency in the sentences imposed for high range PCA offences with:

- More uniformity in the use of s 10 non-conviction orders between the courts. In Sydney courts, the use of s 10 orders fell from 5.7% in the equivalent 2003 period to 3.3% in the pre-guideline period to 0.9% in the post-guideline period. While the use of s 10 orders was higher for courts located outside Sydney they also declined from 14.7% in the equivalent 2003 period to 8.2% in the pre-guideline period to 3.4% in the post-guideline period.

- More uniformity in the length of disqualification periods between the courts.

- A clear distinction in sentencing patterns between first offenders, subsequent offenders and subsequent offenders where the prior offence was high range PCA — although there was a clear distinction prior to the guideline, after the guideline it was even more accentuated.

Appeals

- Appeals to the District Court against severity of sentence increased slightly.

- The success rate of severity appeals was around 80%. After the guideline judgment the success rate increased in cases where full-time imprisonment was imposed at first instance.

- Re-sentencing outcomes of successful severity appeals were less likely to result in a variation in the type of penalty imposed at first instance and more likely to result in a variation of the amount or duration of the penalty, especially where the first instance penalty was a term of full-time imprisonment.

- Little difference in the proportion of defendants who had their disqualification period varied, except where the first instance penalty was full-time imprisonment.

Flow-on effects

There has been a flow-on effect to other PCA offences with:

- A further reduction in the use of s 10 non-conviction orders, even though they had already fallen in the early part of 2004.

- A corresponding increase in the proportion of offenders disqualified from driving.

- Longer disqualification periods — more offenders getting the automatic, rather than the minimum, disqualification periods, especially for middle range PCA offences.

In conclusion, Local Courts appear to be following and applying the guideline judgment and imposing increased levels of sentencing for high range PCA offences. But with the effluxion of time, there may be a need to re-examine sentencing patterns for high range PCA offences.

Appendix

The Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999 distinguishes between the statutory maximum penalties applicable to a “first offence†and a “second or subsequent offenceâ€.

Clause 2 of the dictionary defines first offences and second or subsequent offences as follows:

“(1) An offence against a provision of this Act is a ‘second or subsequent offence’ only if, within the period of 5 years immediately before a person is convicted of the offence, the person was convicted of another offence against the same provision or of a major offence.

(2) An offence against a provision of this Act is a ‘first offence’ if it is not a second or subsequent offence.â€

The definition of a “major offence†has the same meaning as it has in the Road Transport (General) Act 1999, that is:

â€â€˜major offence’ means:

(a) a crime or offence referred to in the definition of ‘convicted person’ in section 25 (1), or

(b) any other crime or offence that, at the time it was committed, was a major offence under this Act or the Traffic Act 1909.â€

Under s 25(1) the definition of:

“‘convicted person’ means:

(a) a person who is, in respect of the death of or bodily harm to another person caused by or arising out of the use of a motor vehicle driven by the person at the time of the occurrence out of which the death of or harm to the other person arose, convicted of:

(i) the crime of murder or manslaughter, or

(ii) an offence under section 33, 35, 53 or 54 or any other provision of the Crimes Act 1900, or

(b) a person who is convicted of an offence under section 51A of the Crimes Act 1900, or

(c) a person who is convicted of an offence under any of the following provisions:

(i) section 42 of the Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999 of driving a motor vehicle on a road or road related area furiously or recklessly or at a speed or in a manner which is dangerous to the public,

(ii) section 42 of the Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999 of driving a motor vehicle negligently (being driving occasioning death or grievous bodily harm),

(iii) section 43 of the Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999,

(iv) section 9 (1A), (1), (2) (a) or (b), (3) (a) or (b), (4) (a) or (b) or section 15 (4) or 16 of the Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999,

(v) section 22 (2) of the Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999,

(vi) section 12 (1) (a) or (b) of the Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999,

(vii) section 29 (2) of the Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999,

(viii) section 70 of the Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999, or

(d) a person who is convicted of aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring the commission of, or being an accessory before the fact to, any such crime or offence.

‘conviction’ means the conviction in respect of which a person is a convicted person.â€

Note: For some offences under the Crimes Act 1900, it was impossible to discern whether an offence involving the death of or bodily harm to another person was caused by or arose out of the use of a motor vehicle driven by the offender. Nevertheless, the number of cases would be small and would have little impact on the results of this analysis.

Endnotes

1 Section 10 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 provides, inter alia: “(1) Without proceeding to conviction, a court that finds a person guilty of an offence may make any one of the following orders: (a) an order directing that the relevant charge be dismissed, (b) an order discharging the person on condition that the person enter into a good behaviour bond for a term not exceeding 2 years, (c) an order discharging the person on condition that the person enter into an agreement to participate in an intervention program and to comply with any intervention plan arising out of the program.” Section 10 sets out a number of factors relevant to the imposition of a s 10 order.

2 Comprising Spigelman CJ, Wood CJ at CL, Grove, Dunford and Howie JJ.

3 Application by the Attorney General under Section 37 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act for a Guideline Judgment Concerning the Offence of High Range Prescribed Concentration of Alcohol Under Section 9(4) of the Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999 (No. 3 of 2002) (2004) 61 NSWLR 305.

4 ibid at [146].

5 ibid at [146].

6 See, for example, R v Jurisic (1998) 45 NSWLR 209; R v Henry (1999) 46 NSWLR 346; R v Wong and Leung (1999) 48 NSWLR 340; and R v Whyte (2002) 55 NSWLR 252.

7 In the case of high range PCA offences, the vast majority of s 10 orders (95.7%) involved conditional discharges.

8 5 May 2004.

9 These studies (by the Judicial Commission of NSW, Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Roads and Traffic Authority, and others) are referred to several times in the guideline judgment.

10 Contained on JIRS (Judicial Information Research System), a database established and maintained by the Judicial Commission of NSW.

11 op cit n 3 at [134].

12 op cit n 3 at [97].

13 op cit n 3 at [12].

14 op cit n 3 at [133].

15 op cit n 3 at [127].

16 op cit n 3 at [143].

17 op cit n 3 at [103] and [134].

18 If two or more offences attracted the same penalty, then the first offence in the list was selected as the principal offence.

19 While the earliest period in 2004 (January to April) revealed an average use of s 10 orders one per cent below the equivalent 2003 period, this was mostly due to an anomaly in January 2004. When cases sentenced during January were excluded, the average use of s10 orders was much closer to the comparison group (10% compared with 10.3%).

20 Because instances of being in the driver’s seat and attempting to put the vehicle in motion (s 9(4)(b)) or supervising a learner driver (s 9(4)(c)) appear to be rare and atypical, the court only regarded high range PCA offences where the person drives the vehicle. See op cit n 3 at [138].

21 Maximum penalty: 30 penalty units or imprisonment for 18 months or both (in the case of a first offence) or 50 penalty units or imprisonment for 2 years or both (in the case of a second or subsequent offence).

22 Relevant prior offending data were provided by BOCSAR. There were a small number of offenders who had previously been found guilty of a major offence within five years, however they had not been convicted. These cases have been excluded from the analysis relating to second or subsequent offenders. In this study, a convicted person does not include a person “found guilty” where a non-conviction order under s 10 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act1999 (or previously under s 556A of the Crimes Act 1900) was made. The omission of the phrase in s 25(1) of the Road Transport (General) Act 1999 “or found guilty” found in other parts of the Road Transport legislation evinces an intention by Parliament to exclude offenders who have previously received a s 10 order. See, for example, RTA v Weir (2004) 60 NSWLR 304 at [6] and [8], where it was held that a previously imposed s 10 order where the court did not proceed to conviction came within the phrase “found guilty of” an offence but distinguishable from a “conviction”. It should be noted, however, that a s 10 order cannot be imposed on a PCA offender who has already had the benefit of a non-conviction order within five years of the current conviction: see s 24 of the Road Transport (General) Act 1999. In HA & SB v DPP (2003) 57 NSWLR 653, the court held that a finding of guilt under the Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987 amounted to a conviction for the purposes of the disqualification provisions, partly because s 33(5)(a) of the Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987 expressly states that disqualification provisions are not affected.

23 The different systems do not use a single common identifier.

24 As mentioned earlier, the analysis is based on the principal offence. In this study, approximately 93% of high range PCA offences were selected as the principal offence (91.7% in the equivalent 2003 period, 92.4% in the pre-guideline period and 94.7% in the post-guideline period).

25 Fines can also be imposed with other penalties considered to be higher in the sentencing hierarchy, for example, s 9 bonds and community service orders. In such cases, only the primary penalty is recorded. Consequently, fines can only be selected as the primary penalty if they have not been imposed with any other penalty.

26 op cit n 3 at [133] and [134].

27 Courts have not been identified by name but rather according to the Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC), 2001, Australian Bureau of Statistics (Catalogue No 1216.0).

28 Section 17 of the Crimes (Local Courts Appeal and Review) Act 2001.

29 (1989) 42 A Crim R 81 at 87.

30 Because of the difficulties linking data from District Court appeal cases with Local Court first instance cases, only an estimate of the proportion of first instance matters that were appealed has been calculated — by dividing the number of appeals by the number of first instance cases for each period. Since only high range PCA offences that were selected as the principal offence were analysed for this study, it was necessary to include high range PCA offences that were not selected as the principal offence in the total number of first instance matters. As such, these figures were calculated from a total of 1,586 cases in the equivalent 2003 period, 1,439 cases in the pre-guideline period and 1,442 cases in the post-guideline period.

31 The study by BOCSAR was released on 27 February 2004 and is one of the studies discussed at the hearing to determine whether to issue a guideline judgment for high range PCA offences. See S Moffatt, D Weatherburn and J Fitzgerald, “Sentencing drink-drivers: The use of dismissals and conditional discharges” (2004) 81 Crime and Justice Bulletin 1.

32 In the case of middle range PCA offences, there were 3,738 cases in the equivalent 2003 period, 3,379 cases in the pre-guideline judgment period and 3,702 cases in the post-guideline judgment period. The number of cases of low range PCA offences were 1,644, 1,558 and 1,881, respectively.