Patrizia Poletti

Principal Research Officer (Statistics)

Pierrette Mizzi

Manager, Research and Sentencing

Hugh Donnelly

Director, Research and Sentencing

INTRODUCTION

This publication focuses on sentencing for the offence of sexual intercourse with a child aged under 10 (s 66A Crimes Act 1900) for the period from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2014. It also compares past and present sentencing practices.

The Judicial Commission has recently supplied the NSW Sentencing Council,1 the Joint Select Committee on Sentencing of Child Sexual Assault Offenders2 and the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse with comprehensive information concerning sentencing for this offence. This publication builds and expands upon that material. The Joint Select Committee recommended that sentencing information about child sexual assault should be made more readily available to the public.3 Since that report was published a Judicial Commission study found that NSW had harsher sentences of imprisonment than Victoria and Queensland for sexual assault of a child under 10.4

The offence under consideration has been amended by Parliament more than any other offence since 2003.5 The maximum penalty of life imprisonment and the relatively high standard non-parole period (SNPP) of 15 years is a clear indication that Parliament regards it as among the most heinous of all offences. The recent increase in the maximum penalty for any s 66A offence reflects a more punitive approach by the legislature towards these offenders.6 The most recent reform, the substitution of s 66A by the Crimes Legislation Amendment (Child Sex Offences) Act 2015, was also influenced by the hearings of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.7

It is well known that sentencing for this serious offence can be complex and there is no better example of this than the High Court decision of Muldrock v The Queen.8 The High Court held that the 15-year SNPP had little role to play in the sentencing exercise for an offender who suffered from an intellectual disability.9 The High Court was to reiterate in a later case:10

The administration of the criminal law involves individualised justice, the attainment of which is acknowledged to involve the exercise of a wide sentencing discretion.

In a publication of this size it is not possible to ventilate all the issues associated with the offence. Part I contains a legal discussion which sets out the legislative history of the offence, relevant SNPP case law and key sentencing considerations that may influence the severity or leniency of a particular sentence. Part II of the publication then focuses on an empirical analysis of offenders and sentencing for the offence.

PART I: LEGAL ANALYSIS

Legislative history and significant standard non-parole period cases

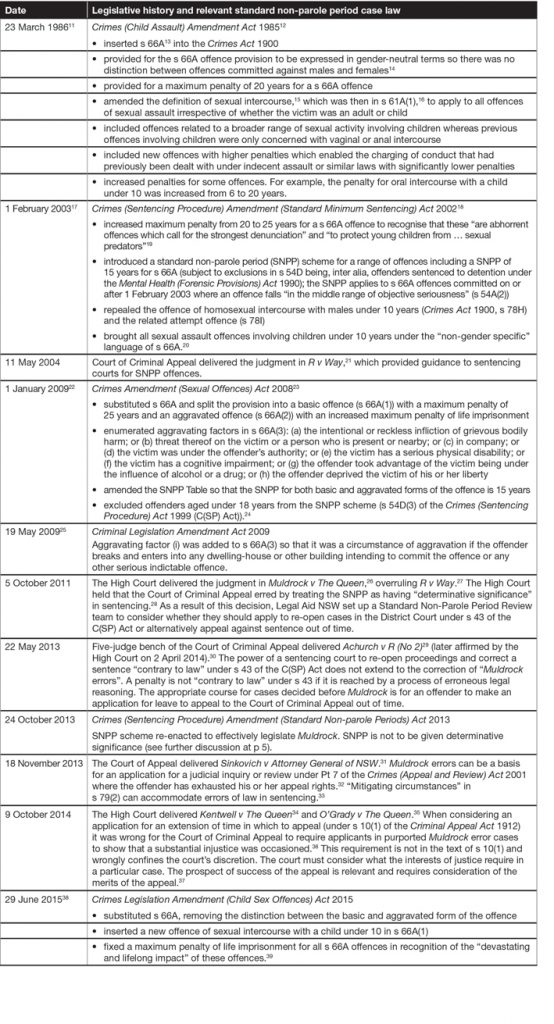

The information in Table 1 sets out the legislative history for the offence and relevant SNPP law. It explains the complex litigation that occurred to correct purported Muldrock error cases.

Table 1: Legislative history of s 66A since 1986 and relevant case law

Sentencing considerations

Muldrock v The Queen,40 the High Court said the approach to sentencing (consistently with what McHugh J explained in Markarian v The Queen)41 requires that the judge:

… identifies all the factors that are relevant to the sentence, discusses their significance and then makes a value judgment as to what is the appropriate sentence given all the factors of the case. [Emphasis added.]

Generally, in determining the appropriate sentence, the relative importance of the objective and subjective features vary and a judge must impose a sentence that does not give undue attention to subjective considerations causing inadequate weight to be given to the objective circumstances of the case.42 In undertaking the sentencing exercise for a s 66A offence, the task of the judge is to consider numerous factors. The factors below are some of the matters which have the most impact upon the sentence imposed.

The maximum penalty

The maximum penalty is one of two important legislative guideposts as to the appropriate sentence,43 particularly with respect to s 66A offences where the maximum penalty is life imprisonment.44 It is reserved for the worst category case45 and reflects the legislatures attitude of the seriousness of the offence. Whether this criteria is met is determined by considering the nature of the criminal conduct viewed against the prescribed maximum penalty.46

The maximum penalties that have existed for the offence are set out in Table 1, above. An increase in the maximum penalty is a signal to the courts that sentences should increase.47 When a maximum penalty is increased it applies prospectively and never retrospectively.48

Fixing the maximum penalty at life recognises the heinousness of s 66A offences and their devastating and lifelong impact.49 Once all relevant sentencing matters have been considered, the sentence should reflect the seriousness of the offence and be proportionate to the crime and the circumstances of the offender. The High Court explained in Elias v The Queen:50

It is wrong to suggest that the court is constrained, by reason of the maximum penalty, to impose an inappropriately severe sentence on an offender.

A sentence of imprisonment can be imposed only if the court thinks no other sentence is appropriate.51 The statistical analysis in Part II shows that full-time imprisonment is overwhelmingly the most common sentence for s 66A offences. Cases where a sentence of full-time imprisonment was not imposed were infrequent and there were unique features justifying that course of action.52

Standard non-parole periods

One of the challenges of this study is that sentencing law changed markedly between 2008 and 2014. The precise role SNPPs played in the sentencing process was first established by the Court of Criminal Appeal in R v Way.53 Nearly seven years later,R v Way was overruled by the High Court in Muldrock54 In Muldrock, the High Court said the objective seriousness of an offence was to be determined wholly by reference to the nature of the offending and without reference to matters personal to a particular offender and that a court is not required to compare a particular offence with a hypothetical mid-range offence.55 Further, the SNPP should not be given determinative significance56 but is an important guidepost for any offence regardless of whether the offender pleads guilty or is convicted after trial.57

The SNPP scheme was re-enacted in late 2013.58 The amendments effectively legislated what had been held in Muldrock as set out above in Table 1. Section 54B(2) of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (C(SP) Act) now requires a judge to take the SNPP into account without limiting the matters that are otherwise required or permitted to be taken into account. Section 54A(2) now states that the SNPP represents:

the non-parole period for an offence that, taking into account only the objective factors affecting the relative seriousness of that offence, is in the middle of the range of seriousness. [Emphasis added.]

The SNPP is a legislative guidepost for offences falling within the middle of the range of seriousness.59 It is not to be used as a starting point60 for sentencing offenders and the court is not required to identify the extent to which the seriousness of the offence for which the non-parole period is set differs from that of an offence to which the standard non-parole period is referable.61

General deterrence

The courts have said repeatedly that general deterrence is to be attributed significant weight for child sexual assault. It requires the imposition of severe sentences because of the particular vulnerability of young children and the well-known long-term effects of child sexual assault.62 It is especially important when the offender is in a position of trust63 because children are entitled to be safe and to feel protected when in the company of persons who stand in a position of trust in relation to them.64 This is particularly so in the family context where children are virtually helpless and have a right to be protected from sexual molestation within the family [which] can only be achieved by the courts imposing sentences of a salutary nature.65

Circumstances of the offence

The heinousness of the conduct in a particular case is determined by considering the entirety of the particular facts and circumstances.66 There is no strict hierarchy of seriousness based on the type of intercourse, with penile-vaginal intercourse at the apex.67 Nor is digital intercourse, of itself, less serious than other forms of intercourse.68 A relevant factor is also whether or not physical injury was inflicted by the act of intercourse. Penile penetration could be the most serious form of sexual assault in relation to young children because it is the most likely to result in physical injury to them.69

Between 1 January 2009 and 28 June 2015, Parliament expressly identified in s 66A(3) a number of circumstances of aggravation for offences against what was then s 66A(2).70 One feature of these offences is that frequently the victim is under the authority of the offender who, in many cases, is in the position of a father-figure.71 When a father is the offender, the breach of trust has been described as gross.72

The victims age may be a relevant consideration notwithstanding that age is also an element of the offence. This recognises the entire class of children under the age of 10 years as being vulnerable.73 A finding that the objective seriousness of an offence is aggravated under s 21A(2)(l)74 of the C(SP) Act because of the victims age may be made even though age is an element of the offence because the younger the victim the more serious the offence.75 When the victims age is well below the statutory ceiling of 10 years it may be an aggravating factor.76 When offences are committed against more than one victim, the fact that one was younger than another may make an offence more serious, by a degree.77

Other relevant circumstances include:

- how the offence took place

- the period of time of the offending behaviour

- the degree of force or coercion

- the use of threats or pressure before or after the offence to ensure the victims compliance with the demands made, and subsequent silence

- any immediately apparent effect on the victim.78

It is an inherent aspect of these offences that they involve the sexualisation of children and are carried out for sexual gratification.79 That fact should not be given separate consideration as an aggravating factor.80 In rare cases, however, an offence against s 66A has been found not to be motivated by sexual gratification.81 In such cases, other factors such as the extent of the violence, the effect on the victim and their age were important considerations.82

Grooming the victim is a circumstance of aggravation.83

The use of force aggravates an offence. However, an absence of force will not necessarily result in a finding that an offence is at the lower end of the range. This is because one aspect of the seriousness of these offences is that young children do not have the ability to resist or protect themselves. That these offences can be committed without resort to force speaks of a pernicious abuse of trust.84

When a sexual assault involves violation of the expectation of safety and security in the home, the offence may be considered more serious.85 In Ingham v R, the fact that the offending involved the abuse of two children over a weekend at one of the victims homes violated their legitimate expectation that [the victims] home was a place of safety and refuge.86

Effect of crime on victim87

Courts are entitled to act on the basis that child sexual assault causes substantial psychological harm.88 It is well-recognised that these offences have significant and adverse psychological consequences on young children.89 Fixing a maximum penalty of life imprisonment is taken to be a reflection of the fact that substantial harm is suffered by child victims.90 The effect on victims and an appreciation of the likelihood of harm has helped change community attitudes to child sexual assault.91

Taking additional charges into account (Form 1 matters)

Section 32 of the C(SP) Act permits a court sentencing for the principal offence to take into account on a Form 1 other charged offences an offender has admitted but in respect of which he or she has not been convicted. This procedure is subject to the limitations in s 33(4). Section 33(4)(b) prohibits the inclusion on a Form 1 of an offence with a maximum penalty of life imprisonment. Taking a Form 1 into account permits greater weight to be attributed to specific deterrence and retribution, although the focus remains on the principal offence. The result is that an increased penalty, which in some cases may be substantial, is imposed.92

As all s 66A offences now attract a maximum penalty of life imprisonment it will not be possible to use the Form 1 procedure for offences committed on or after 29 June 2015.

Representative charges

Where an offender is sentenced for an offence which is representative of a course of conduct over a period of time, the overall circumstances can be taken into account to rebut any suggestion that the offence is an isolated incident. The court is permitted to place the offence in its proper context.93

Guilty plea

Section 22 of the C(SP) Act requires a court to take into account an offenders guilty plea. It is usual, but not mandatory, for a court to give a discount of up to 25% for pleading guilty at the first opportunity.94 A guilty plea means the victim is not required to give evidence at a trial. This is a factor which may justify the reduction of the sentence and may also be evidence of remorse. However, the fact an offender pleads not guilty, which results in the victim having to go through the stress of giving evidence, is not to be treated as an aggravating factor.95

Prior record/good character

Prior record is relevant to whether an offender may have a claim for leniency96 or whether a particular offence demonstrates a continuing attitude of disobedience of the law.97 Although good character must be taken into account on sentence, the weight given to it as a mitigating factor varies depending on the circumstances of the offence.98 Prior good character is of less significance in cases of child sexual assault, particularly in cases involving repeated offending against young children.99 Additionally, the fact an offender being sentenced for a s 66A offence has no prior record may need to be considered in light of s 21A(5A) of the C(SP) Act. The provision prevents a court sentencing an offender for a child sexual offence100 from taking into account an offenders prior good character, or lack of previous convictions, if that fact assisted them to commit the offence. Section 21A(5A) does not apply when there is a family relationship between the offender and the victim, and is limited to when an offender used his or her position to obtain access to children.101

Mental condition

In Muldrock, a mentally disabled offender with a prior (interstate) record committed a s 66A offence. An offence of indecent assault was also taken into account on a Form 1. The case highlights the impact and significance of mental illness as a sentencing consideration. Section 21A(3)(j) of the C(SP) Act requires consideration of the fact an offender was not fully aware of the consequences of his or her actions because of any disability. Even when the relevant disability does not amount to a serious mental illness, it may be taken into account.102

The courts have held that a lesser sentence may be imposed for an offender suffering from a mental condition on the basis that:

- there is a causal connection between the mental illness and the commission of the offence which, in most cases, will reduce the offenders moral culpability103

- general deterrence may be of less significance because it is not appropriate to make the mentally ill an example to others104

- custodial sentences may weigh more heavily on the mentally ill105

- the need for the sentence to reflect specific deterrence may be reduced or eliminated.106

Conversely, offenders suffering from a mental illness may also present more of a danger to the community, in which case considerations of specific deterrence may assume greater significance and may result in an increased sentence.107

In Muldrock, the High Court stated that the 15-year SNPP had little if any role to play when sentencing mentally ill offenders because it said little about the appropriate sentence.108

Totality

When an offender is sentenced for more than one offence the overall sentence must be just and appropriate and reflect the totality of the offending behaviour involved.109 The proper application of the totality principle is significant because most offenders charged with a s 66A offence are sentenced for more than one offence. Those other offences are usually child sexual assault offences.110

Aggregate sentencing pursuant to s 53A of the C(SP) Act, which was introduced in March 2011,111 was intended to overcome some of the difficulties associated with sentencing for multiple offences, to simplify the sentencing process and to focus attention on the overall conduct rather than on an individual offence. The part of the statistical analysis that focuses on the penalty imposed for a principal s 66A offence must always be understood as the sentence for only one offence. It does not always reflect the overall period of incarceration.

Totality can also be accommodated in cases where there are multiple counts by the prosecution proceeding under s 66EA of the Crimes Act 1900 (persistent sexual abuse of a child on 3 or more occasions). A sexual offence in s 66EA includes a s 66A offence.112 The maximum penalty for s 66EA offences is 25 years imprisonment, lower than the maximum for a s 66A offence.

Delay

Delay between the offence and sentencing is common for these offences. Whether delay is relevant will depend on the circumstances of the particular case.113 Mere delay in complaint by the victim will not usually justify leniency in sentence.114 An offender who remains silent about offending is not to be rewarded for the successful concealment of an offence by a substantially reduced sentence.115 Where there has been long delay and sentencing law has moved adversely to the offender the court must take account of past sentencing practices.116 Delay may operate to mitigate a sentence where an offender has demonstrated the capacity to live a law abiding lifestyle.117

The relevance of statistics and comparable cases

In seeking consistency, the sentence imposed in an individual case is determined by reference to what has occurred in previous cases.118 While there are recognised limitations when using statistics and comparable cases, such material is useful because it shows historical sentencing patterns and has some utility as a guide or check.119 Greater caution is necessary for s 66A offences because:

- there are no single unifying features which mark out a typical offence given the broad range of circumstances in which these offences can be committed120

- the legislative history of s 66A makes it difficult to identify sufficient numbers of comparable cases within the operative time frame of a particular version of the offence.121

Using comparable cases decided when the relevant sentencing principles were derived from R v Way is problematic.122 This is because, in cases decided before Muldrock, it is not possible to identify whether the SNPP was used in determining the appropriate sentence in an impermissible way, that is, by giving it too much weight in a particular sentencing exercise.123

PART II: STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

This section examines the sentencing patterns for offenders convicted of s 66A offences.124 Part II also reports the types and outcomes of sentence appeals.

Methodology

The analysis includes offenders who were sentenced, at first instance, during the 7-year period 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2014 (the reference period). The period commences on 1 January 2008 because an earlier Judicial Commission study, assessing the impact of the SNPP scheme, examined sentencing patterns for SNPP offences, including s 66A offences for the period 3 April 2000 to 31 December 2007.125 The fact that s 66A offences are strictly indictable means that every offender in this study, including juveniles,126 was dealt with in the District Court.

First instance sentencing data were provided by the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) and have been adjusted to take into account the outcomes of successful conviction or sentence appeals to the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal and the High Court of Australia.127 Data on appeals were sourced from a database maintained by the Judicial Commission of NSW.

The data are appearance (or person) based, so that where an offender has been sentenced in more than one finalised court appearance during the reference period, the sentence imposed in each finalised court appearance is included.128 However, sentences imposed following breaches by offenders of suspended sentences and good behaviour bonds are not included.

This study includes offenders with at least one proven s 66A offence. If the offender was convicted of two or more s 66A offences, the offence with the most severe penalty was selected for analysis (the principal offence).129 Additional information about the circumstances of the offence was obtained. The information included the victims age and gender, the type of sexual intercourse engaged in, and the relationship between the offender and the victim. The sources used included the indictments, court papers, and judgments at first instance and on appeal.

Section 66A offences are charged like other sexual offences. It is common for a charge to incorporate a date range.130 Where a range was specified, the first date was selected as the offence date. The offence date was used to calculate the ages of the offender and the victim at the time of the offence, and the period between the offence and sentence dates (indicating the delay).

The analysis excludes two offenders who were diverted to a treatment program under the Pre-Trial Diversion of Offenders Act 1985,131 but includes one offender who was resentenced after breaching the pre-trial diversion order.132

The offence categories under s 66A

A major focus of this study is to compare sentences for s 66A offences dealt with under different sentencing regimes identified in the legislative history in Table 1 particularly with regard to the statutory maximum penalty and the SNPP. The analysis includes determining the impact on sentencing (if any) of the High Court decision in Muldrock v The Queen.133 Juvenile offenders and offenders sentenced to detention under the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990, who are excluded from the SNPP scheme, have also been excluded from this part of the analysis. The sentences for juveniles and offenders dealt with by way of a special hearing are analysed separately.

To reflect the different sentencing regimes and the amendments to s 66A since its enactment in 1986, the data were grouped as follows:134

- s 66A (before SNPP) offences (committed from 23 March 1986 to 31 January 2003)

- s 66A (with SNPP) offences (committed from 1 February 2003 to 31 December 2008)

- s 66A(1) (basic) offences (committed from 1 January 2009)

- s 66A(2) (aggravated) offences (committed from 1 January 2009).

Prior to 2009, no distinction was drawn between basic and aggravated forms of the offence.

Statistical tests

The analysis of the data is primarily descriptive. However, tests of significance are used to ascertain whether any statistically significant bivariate associations were found between various factors and sentencing patterns. The statistical tests used include the chi-square test (for categorical data, such as gender and plea); and the Mann-Whitney U test for two independent samples or the Kruskal-Wallis test for more than two independent samples (for interval and ordinal data, such as age and terms of sentence). A significance level of 0.05 is used.

Terminology

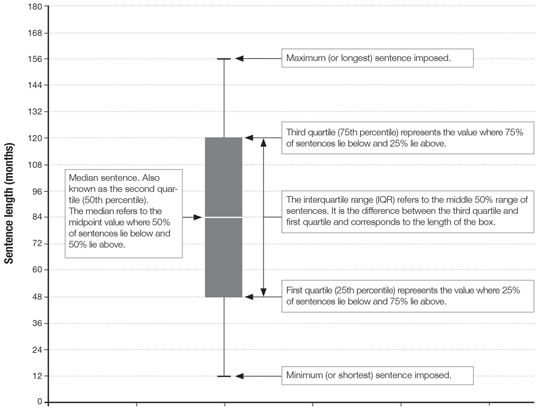

The term median refers to the value which lies in the middle of a range of values (the 50th percentile). The term mean refers to the average value. In many instances, the median will be the preferred statistical measure because the distribution is often skewed by outliers.

In respect of full-time imprisonment (prison sentences), the percentage of sentences falling within the middle 50% range of values is shown. The lower limit of this range is set at the first quartile (or 25th percentile) and the upper limit is set at the third quartile (or 75th percentile). This interquartile range shows the spread of values near the centre.

The full term refers to the total non-parole period (NPP) and balance of term. The NPP refers to the minimum period of time an offender serves in custody.135 These are only referable to the principal offence and do not reflect the overall sentence where an offender has committed multiple offences and the court, applying the totality principle, has imposed either consecutive or partly consecutive sentences. The overall full term and the overall NPP reflect the overall sentence imposed in each case whether the offender committed one or more offence(s). The overall NPP/full term ratio refers to the ratio between the NPP and the full term of the overall sentence. A finding of special circumstances under s 44 of the C(SP) Act was surmised to be made in cases where the overall NPP/full term ratio was less than 75%.136

Cases involving multiple offences, where there has been a degree of accumulation of the various sentences and where the overall full term or overall NPP exceeds the full term or NPP for the principal offence, are referred to as consecutive sentences.

Results of the analysis

Over the 7-year reference period, 222 offenders were sentenced for s 66A offences and in the majority of cases (205 or 92.3%) that offence was the most serious. In 17 cases (7.7%), a different sexual assault offence received the harshest sentence, most commonly aggravated sexual assault under s 61J of the Crimes Act 1900 (9 cases or 4.1%).137

Overall, these 222 offenders were sentenced for 1,355 offences, of which 1,320 were sexual offences138 mainly committed against children, including 523 offences against s 66A. In addition, 19 offenders had, between them, 36 offences against s 66A taken into account on a Form 1.139

Trends

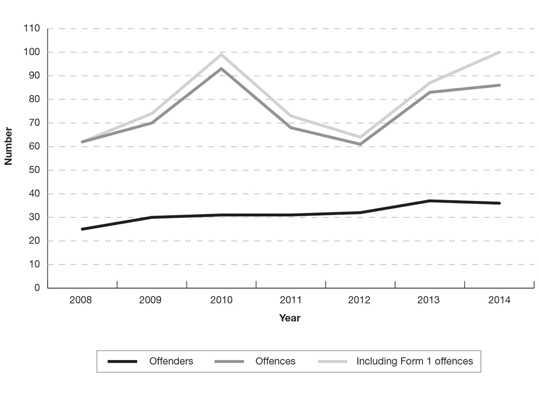

Figure 1 shows the number of offenders and offences against s 66A by year. While the number of offenders increased by 44% over the 7-year reference period (from 25 offenders in 2008 to 36 offenders in 2014),140 the total number of s 66A offences has fluctuated between 61 and 93 offences. Since 2009, the number of s 66A offences taken into account on a Form 1 has ranged from 3 to 6 offences. However, that figure rose sharply to 14 offences in 2014.

Figure 1: Number of offenders and offences against s 66A by reference year

Offender characteristics

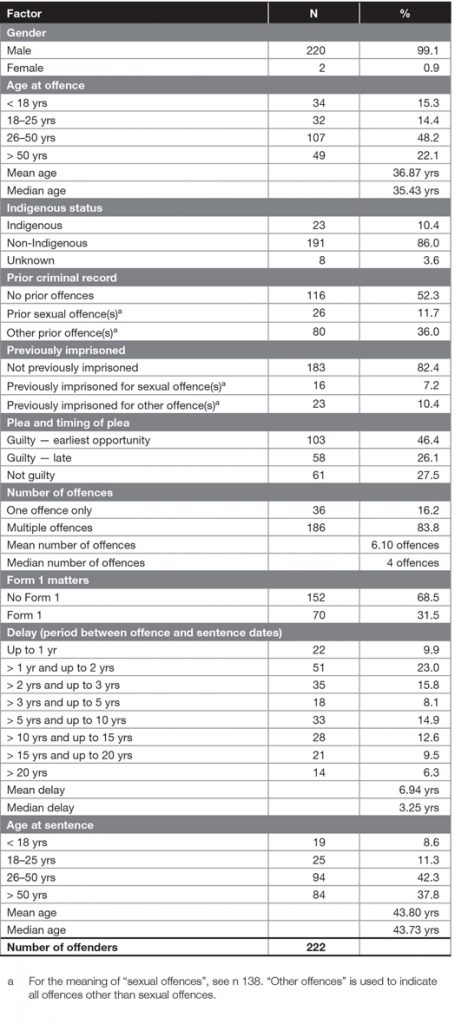

The characteristics of the offenders convicted of s 66A offences in this study are displayed in Table 2 and may be summarised as follows.

Gender: Offenders were predominantly male (99.1%). Only two were female (0.9%).

Age at offence: The mean age of offenders at the time of the offence was 36.9 years and the median was 35.4 years. The youngest offender was aged 11 years and the oldest was 73 years. Those over 50 years accounted for 22.1% and juvenile offenders (those aged under 18 years) accounted for 15.3% of offenders.

Indigenous status: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders accounted for 10.4% of offenders.

Prior record:Just over half (52.3%) of the offenders had no prior criminal record when they were sentenced. Just over one in 10 (11.7%) had committed prior sexual offences, including 7.2% who had previously served a prison term for sexual offences.

Plea and timing of plea: Almost three-quarters (72.5%) of the offenders pleaded guilty: almost half (46.4%) pleaded guilty in the Local Court and just over a quarter (26.1%) were committed for trial but entered a guilty plea either at or after arraignment.141 Just over a quarter (27.5%) of the offenders pleaded not guilty.

Number of offences and the use of a Form 1: The vast majority (83.8%) of offenders were sentenced for multiple offences which on average amounted to 6.1 offences (median = 4 offences).142 Around half (50.5%) were sentenced for multiple

s 66A offences (mean = 2.4; median = 2 offences).143

Almost a third (31.5%) had additional offences taken into account on a Form 1 when sentenced for the principal offence and a further 20 (9.0%) had Form 1 matters attached to another offence.

Overall, 196 offenders (88.3%) were sentenced for multiple offences and/or had further offences taken into account on a Form 1.

Table 2: Offender characteristics (principle offence only)

Delay (period between offence and sentence dates)

The shortest period from the date of offence to the date of sentence was 149 days (just under 5 months) and the longest was 9,546 days (just over 26 years). As Table 2 shows, the mean period of delay was 6.9 years and the median was 3.3 years.144

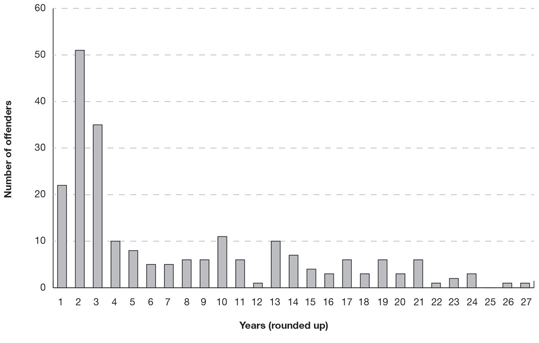

Figure 2 shows the period between the offence and sentence dates for s 66A offences. The most common period was more than 1 year and up to 2 years (23.0%).

Figure 2: Period between offence and sentence dates

A significant number of offenders were dealt with many years after the offence was committed:

- 33 offenders (14.9%) were sentenced more than 5 and up to 10 years

- 28 offenders (12.6%) were sentenced more than 10 years and up to 15 years

- 21 offenders (9.5%) were sentenced more than 15 years and up to 20 years

- 14 offenders (6.3%) were sentenced more than 20 years after.

One likely reason for this is the delay in victims making complaints.145

Predictably, the longest delays were associated with offences committed before 2003. The mean delay was 15.8 years (median = 15.5 years) for offences under s 66A (before SNPP). The delay period was much shorter for offences under s 66A (with SNPP) (mean = 4.6 years; median = 3.3 years), basic offences under s 66A(1) (mean = 1.7 years; median = 1.4 years) and aggravated offences under s 66A(2) (mean = 2.0 years; median = 1.9 years).

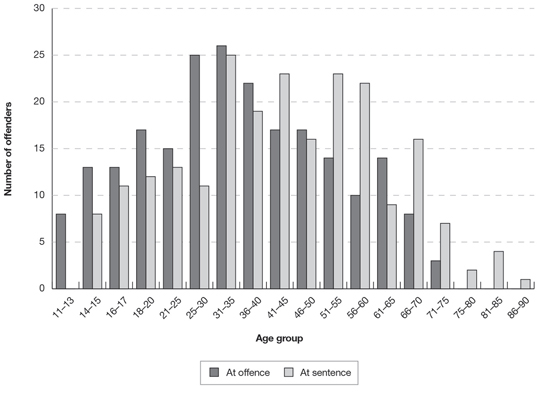

Age at sentence: The delay means that many offenders are considerably older when they are sentenced compared to when the offence was committed. The mean age at sentence was 43.8 years and the median was 43.7 years. The youngest offender at the time of sentence was aged 14 years and the oldest was 86 years. Over a third (37.8%) were aged over 50 years. Figure 3 shows the age distribution of offenders when the offence was committed and at sentence.

Figure 3: Age of offenders at offence and at sentence

Offence characteristics

Tables 3 and 4 show the characteristics of s 66A offences analysed in this study, broken down for juvenile and adult offenders. Table 4 (on p 18), in particular, provides specific information about the relationship between the offender and the victim.

As mentioned above, the vast majority of offenders were sentenced for multiple offences. The circumstances of the offending varied. In some cases it involved only one child but in other cases the offending involved multiple victims of one or both genders. The following information is provided for the principal offence only.

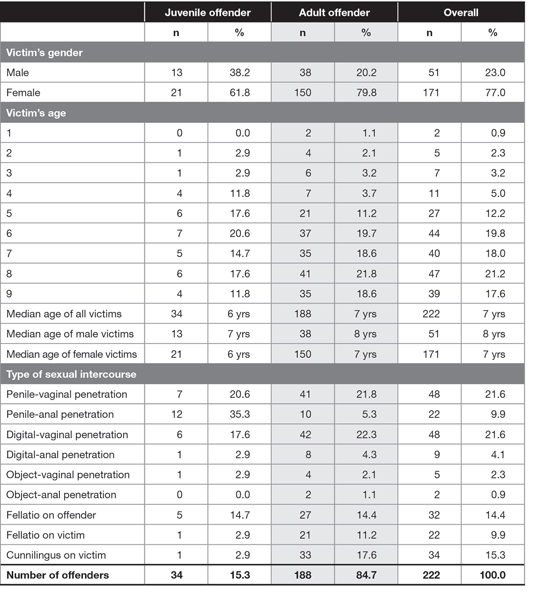

Table 3: Offence characteristics for juvenile and adult offenders (principal offence only)

Gender and age of victims

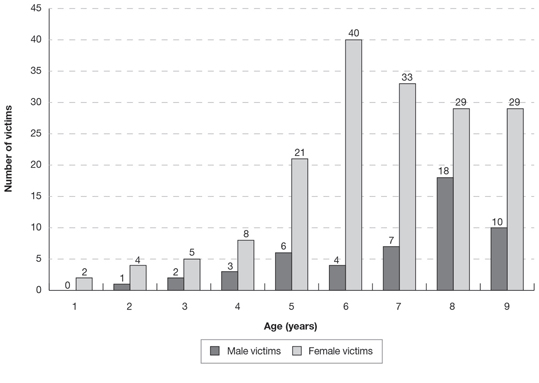

Most victims were female (77.0%) while 23.0% were male. The age distribution by gender of victim in Figure 4 shows that females outnumbered males in every age group.

The two youngest victims were female (one 13 months and another around 14 months), whereas the youngest male was aged 2 years. As Figure 4 shows, female victims were generally younger than male victims. Just over a third (33.9%) of female victims were aged 8 or 9 years compared with over half (54.9%) of male victims. The median age for female victims was 7 years and 8 years for male victims. The most common age for female victims was 6 years (23.4%) and 8 years for male victims (35.3%). The observed differences in the age distributions, however, were not statistically significant.146

Figure 4: Age of victims by gender (principal offence only)

Table 3 shows that juvenile offenders were almost twice as likely as adult offenders to abuse male victims (38.2% compared with 20.2%). This finding was found to be statistically significant.147 However, there was no significant difference in the distribution of victims ages for juvenile offenders (median = 6 years) and adult offenders (median = 7 years).148

Type of sexual intercourse

As Table 3 shows, the type of intercourse is closely associated with the victims gender. Since female victims were over-represented in this study, it is not surprising the most common types of intercourse involved penile-vaginal penetration (21.6%), digital-vaginal penetration (21.6%) or cunnilingus (15.3%). Fellatio on the offender (14.4%) or victim (9.9%) was the type of intercourse in almost a quarter of cases and anal penetration occurred in 14.9%.

Relationship of offender to victim

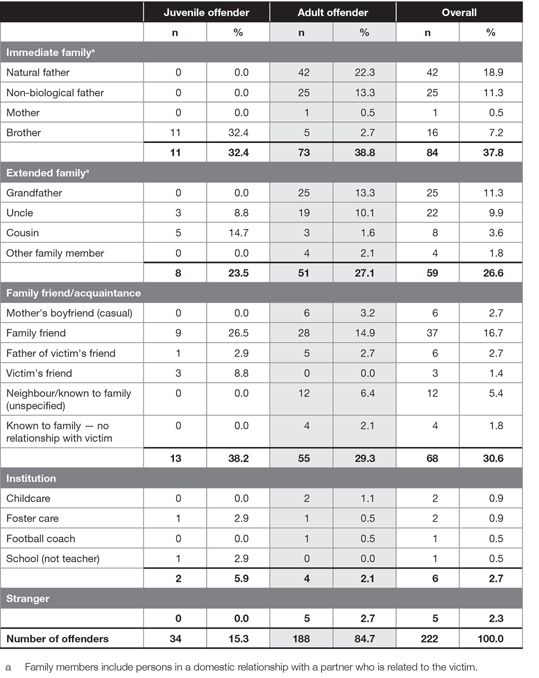

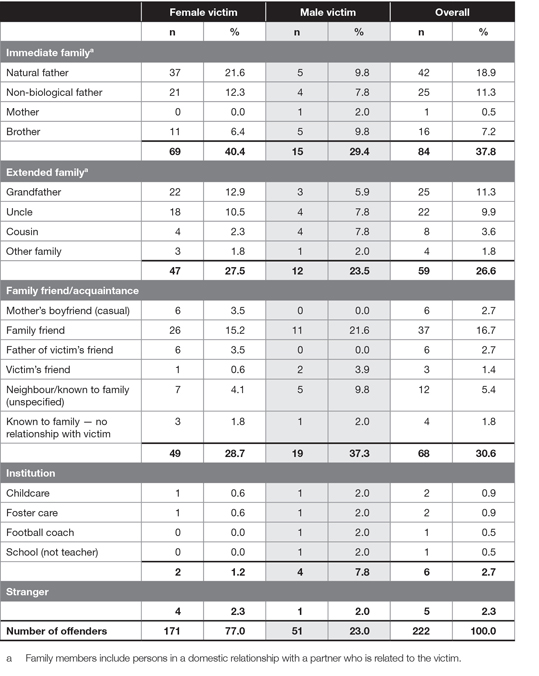

As Table 4 shows, immediate (37.8%) or extended (26.6%) family members149 accounted for much of the abuse against victims. Family friends/acquaintances were responsible for 30.6% of the abuse. Only a small proportion of victims were abused in institutions (2.7%) or by strangers (2.3%).

While no significant difference between juvenile and adult offenders was observed at the broad level,150 there were differences at the more specific level. Juvenile offenders included a brother (32.4%), a family friend (26.5%) or cousin (14.7%) of the victim. Adult offenders were mainly the biological (22.3%) or non-biological (13.3%) father of the victim. A family friend (14.9%), grandfather (13.3%) or an uncle (10.1%) was also a common adult offender.

Table 4: Relationship of juvenile and adult offenders to victim (principal offence only)

Table 5 shows the relationship between the offender and victim according to the victims gender. While no significant difference between female and male victims was observed at the broad level,151 there were some specific differences. Female victims were more likely to be abused by their father, whether biological (21.6% compared with 9.8% male victims) or non-biological (12.3% compared with 7.8%). Although the numbers were very small, male victims were more likely to be abused in institutions (7.8% compared with 1.2% of female victims).

Table 5: Relationship of offender to victim by victim’s gender (principle offence only)

The association between offender and offence characteristics and s 66A offence categories

The aim of this study is to analyse the sentences imposed for s 66A offences dealt with under different sentencing regimes. Therefore, it is important to examine the associations between the offender and offence characteristics discussed above and the various s 66A offence categories, because many of these characteristics impact on the sentence ultimately imposed.

The following significant associations were observed:

- no juveniles were sentenced for a s 66A(2) aggravated offence; and only three were sentenced for offences under s 66A (before SNPP) (4.5%)152

- Indigenous offenders were over-represented in s 66A (with SNPP) offences (22.4%)153

- offenders were more likely to have multiple offences if they were sentenced for offences under s 66A (before SNPP) (98.5%), but less likely to have multiple offences if sentenced for an offence under s 66A(1) (69.0%)154

- offenders sentenced for an offence under s 66A(1) were less likely to have a prior criminal record (26.2%)155

- the longest delays were associated with s 66A (before SNPP) offences (mean = 15.8 years)156

- fathers (52.6%) were over-represented in s 66A(2) offences and unrepresented in s 66A(1) basic offences, while other family members and family friends/acquaintances were over-represented in s 66A(1) basic offences (both 47.6%).157

After juvenile offenders and special hearing cases were excluded, the only significant associations observed for adult offenders were delay,158 the number of offences159 and the relationship between the offender and victim.160

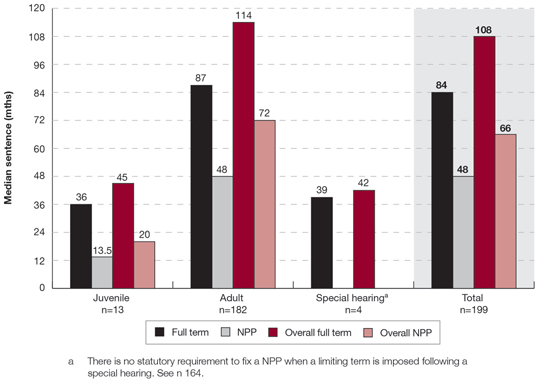

Overview of sentencing patterns

During the study period, the vast majority (89.6%) of offenders sentenced for s 66A offences received a prison sentence. The median full term was 84 months and the median NPP was 48 months. The median overall full term was 108 months and the median overall NPP was 66 months.

Juvenile offenders, in particular, were more likely than adult offenders to receive sentences other than full-time imprisonment (60.6% compared with 1.6%). Figure 5 shows that, when imprisonment was imposed, juvenile offenders and those sentenced following a special hearing161 were sentenced less severely than adult offenders.

Figure 5: Median terms of prison sentences by offender group

Juvenile offenders

It is to be noted that SNPPs do not apply to juvenile offenders from 1 January 2009.

Of the 33 juvenile offenders:

- 13 (39.4%) were sentenced to full-time imprisonment:

- median full term: 36 months (range: 27 to 96 months; middle 50% range: 30 to 50.5 months)

- median NPP: 13.5 months (range: 6 to 42 months; middle 50% range: 8.25 to 26.25 months)

- multiple offences: 11 offenders (84.6%)

- average number of offences: mean 4.5, median 4 (range: 1 to 12)

- consecutive sentences: 11 offenders (84.6%)

- median overall full term: 45 months (range: 29 to 117 months; middle 50% range: 31.5 to 61.5 months)

- median overall NPP: 20 months (range: 8 to 63 months; middle 50% range: 12.5 to 35.5 months)

- finding of special circumstances: 13 offenders (100.0%)

- overall NPP/full term ratio: mean 44.22%, median 40.0%

- 15 (45.5%) received a s 12 suspended sentence, 14 were supervised orders; the median duration was 22 months (range: 15 to 24 months)

- 3 (9.1%) received a s 9 good behaviour bond with supervision, two for 60 months and one for 48 months

- 1 (3.0%) received a supervised suspended control order under s 33(1B) of the Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987 for 24 months

- 1 (3.0%) received a supervised bond under s 33(1)(b) of the Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act for 24 months.

Two juvenile offenders were sentenced for a s 66A (before SNPP) offence and 18 for s 66A (with SNPP) offences, while 13 were sentenced for a s 66A(1) basic offence. Significantly, the offenders dealt with under s 66A(1) were more likely to be given a non-custodial penalty than those dealt with under the legislation in force before 2009 with an equivalent maximum penalty (84.6% compared with 44.4%).162

A closer examination of these two groups of offenders revealed several mitigating and other factors associated with the imposition of non-custodial sentences (19 of 31 cases). The factors included whether the offender: was less than 18 years at the time of sentence; had no prior criminal record; pleaded guilty; and committed only one s 66A offence with no additional charge(s) on a Form 1. The presence of at least three of these factors resulted in a non-custodial sentence (16 cases). In three cases where only two of the factors were present, there were other factors at play. In one case, delay and rehabilitative progress were important factors and the offender had a significant subjective case.163 In another case, the offender suffered from Tourette syndrome and depression. In the remaining case the offender suffered from an intellectual disability.

The higher rate of non-custodial sentences for juveniles sentenced for s 66A(1) offences is explicable by the high frequency of cases where several of these mitigating factors were present, particularly the fact that the offender was less than 18 years at sentence (84.6%) and had no prior criminal record (100%).

Special hearing cases

The SNPP scheme does not apply to offenders sentenced following a special hearing.

Four offenders (three adults and one juvenile) were convicted following a special hearing. Limiting terms164 were imposed on each ranging from 12 to 60 months. The juvenile offender was sentenced for multiple offences and his sentence was accumulated by 2 months resulting in an overall limiting term of 14 months. Another offender also had multiple offences and his sentence was accumulated by 6 months resulting in an overall limiting term of 30 months.

Two offenders were sentenced for a s 66A (before SNPP) offence and another for a s 66A (with SNPP) offence. The remaining offender was sentenced for a s 66A(1) basic offence.

Adult offenders

Of the 185 adult offenders:

- 182 (98.4%) were sentenced to full-time imprisonment:

- median full term: 87 months (range: 18 to 240 months; middle 50% range: 60 to 108 months)

- median NPP: 48 months (range: 1 day to 180 months; middle 50% range: 36 to 72 months)

- multiple offences: 159 offenders (87.4%)

- average number of offences: mean 6.61, median 4 (range: 1 to 120)

- consecutive sentences: 141 offenders (77.5%)

- median overall full term: 114 months (range: 18 to 384 months; middle 50% range: 82.5 to 144.75 months)

- median overall NPP: 72 months (range: 6 to 312 months; middle 50% range: 48 to 102 months)

- finding of special circumstances: 159 offenders (87.4%)

- overall NPP/full term ratio: mean 62.97%, median 65.45

- 2 (1.1%) received a s 12 suspended sentence for 24 months, one with supervision and one without

- 1 (0.5%) received a supervised s 9 bond for 60 months.

Non-custodial sentences: Three adult offenders received a non-custodial sentence. Two were sentenced for a s 66A (before SNPP) offence and one for a s 66A (with SNPP) offence.

The offender who received the s 9 bond was sentenced for a single offence committed on a stranger in 2006. He was 21-years old and suffering from a severe mental condition. He pleaded guilty and had no relevant priors. The bond was imposed partly because of his need for long-term supervision and care.

The first of the two offenders who received a s 12 suspended sentence had committed an isolated offence in 1987 on his 6-year-old niece when he was 33-years old. He was almost 57 at sentence and had no prior convictions. He pleaded guilty at the earliest opportunity.

The second offender was sentenced for an offence committed on his 3-year-old daughter in 1999. He was 27-years old at the time of the offence and almost 40 at sentence. He had been diverted to the (now closed) treatment program under the Pre-Trial Diversion of Offenders Act 1985 after pleading guilty to other offences and disclosed this offence while participating in the program. He pleaded guilty at the earliest opportunity.

NOTE: The remaining analysis (up to Past and present sentencing patterns at p 29) concerns only adult offenders and focuses on sentencing levels for s 66A offences dealt with under different sentencing regimes.

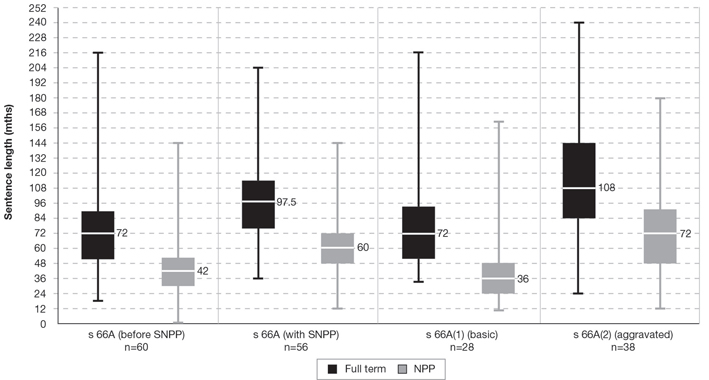

Sentencing patterns for s 66A offence categories

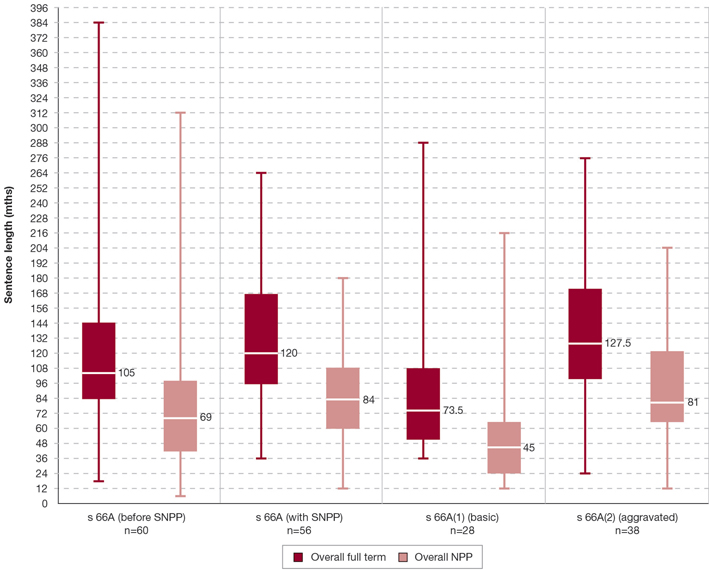

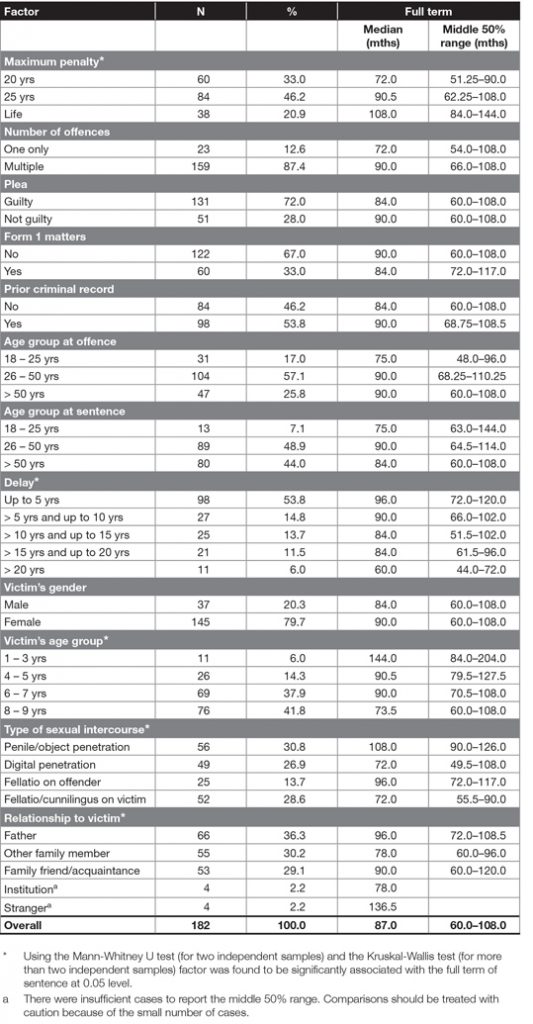

Figure 6 shows the severity of prison sentences imposed for the principal offence (full term and NPP) according to the four sentencing regimes under s 66A, while Figure 7 shows the severity of overall sentences taking into account all offences (overall full term and overall NPP). These figures present box plots (with whiskers from minimum to maximum) to show the distribution (or spread) of sentences. The median is depicted by the line that cuts through the box. The first and third quartiles are depicted by the bottom line and top line of the box respectively. The wider the box, the more variability in the sentences imposed. A sample box plot is provided in Appendix A for further explanation and guidance.

Figure 6: Severity of prison sentences by s 66A offence category (adult offenders)

[Box plot with whiskers from minimum to maximum]

Figure 7: Severity of overall prison sentences by s 66A offence category (adult offenders)

[Box plot with whiskers from minimum to maximum]

Additional sentencing information is provided in Table 6 including the overall NPP/full term ratio, the frequency of a finding of special circumstances and information on a range of offender and offence characteristics.

Table 6: Information concerning sentences by s 66A offence category (adult offenders)

Within each s 66A offence category, there was a wide variation in the terms of prison sentences imposed which reflects the broad nature of the offending and the diverse characteristics of the offenders. Nonetheless, significant differences in the distribution of sentences between the offence categories were observed for the full term,165 NPP,166 overall full term167 and overall NPP.168

The sentencing levels for the four offence categories were as follows.

Section 66A(2) (aggravated) offences (committed from 1 January 2009)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the maximum penalty of life imprisonment, the longest prison sentences were those imposed on offenders sentenced for s 66A(2) aggravated offences:

- median full term: 108 months (range: 24 to 240 months; middle 50% range: 84 to 144 months)

- median NPP: 72 months (range: 12 to 180 months; middle 50% range: 48 to 91.5 months)

- median overall full term: 127.5 months (range: 24 to 276 months; middle 50% range: 99 to 171 months)

- median overall NPP: 81 months (range: 12 to 204 months; middle 50% range: 64.5 to 120 months).

The circumstance of aggravation in the vast majority (86.8%) of s 66A(2) offences was that the victim was under the authority of the offender. The aggravating circumstance in the remaining cases was inflicting actual bodily harm on the victim (7.9%) or depriving the victim of his or her liberty (2.6%). In another case the offender inflicted actual bodily harm on a victim who was also under his authority (2.6%).

Section 66A(1) (basic) offences (committed from 1 January 2009)

The shortest sentences were imposed on offenders sentenced for s 66A(1) basic offences:

- median full term: 72 months (range: 33 to 216 months; middle 50% range: 51.75 to 93.75 months)

- median NPP: 36 months (range: 10 to 162 months; middle 50% range: 24 to 48 months)

- median overall full term: 73.5 months (range: 36 to 288 months; middle 50% range: 51.75 to 107.75 months)

- median overall NPP: 45 months (range: 12 to 216 months; middle 50% range: 24.75 to 64.5 months).

Section 66A (with SNPP) offences (committed from 1 February 2003 to 31 December 2008)

Offenders sentenced for this offence received:

- median full term: 97.5 months (range: 36 to 204 months; middle 50% range: 76.5 to 114.75 months)

- median NPP: 60 months (range: 12 to 144 months; middle 50% range: 48 to 72 months)

- median overall full term: 120 months (range: 36 to 264 months; middle 50% range: 96 to 166.75 months)

- median overall NPP: 84 months (range: 12 to 180 months; middle 50% range: 60 to 108 months).

Section 66A (before SNPP) offences (committed from 23 March 1986 to 31 January 2003)

Offenders sentenced for this offence received:

- median full term: 72 months (range: 18 to 216 months; middle 50% range: 51.25 to 90 months)

- median NPP: 42 months (range: 1 day to 144 months; middle 50% range: 30 to 52.5 months)

- median overall full term: 105 months (range: 18 to 384 months; middle 50% range: 84 to 144 months)

- median overall NPP: 69 months (range: 6 to 312 months; middle 50% range: 42 to 98.25 months).

The association between sentencing factors and prison sentences

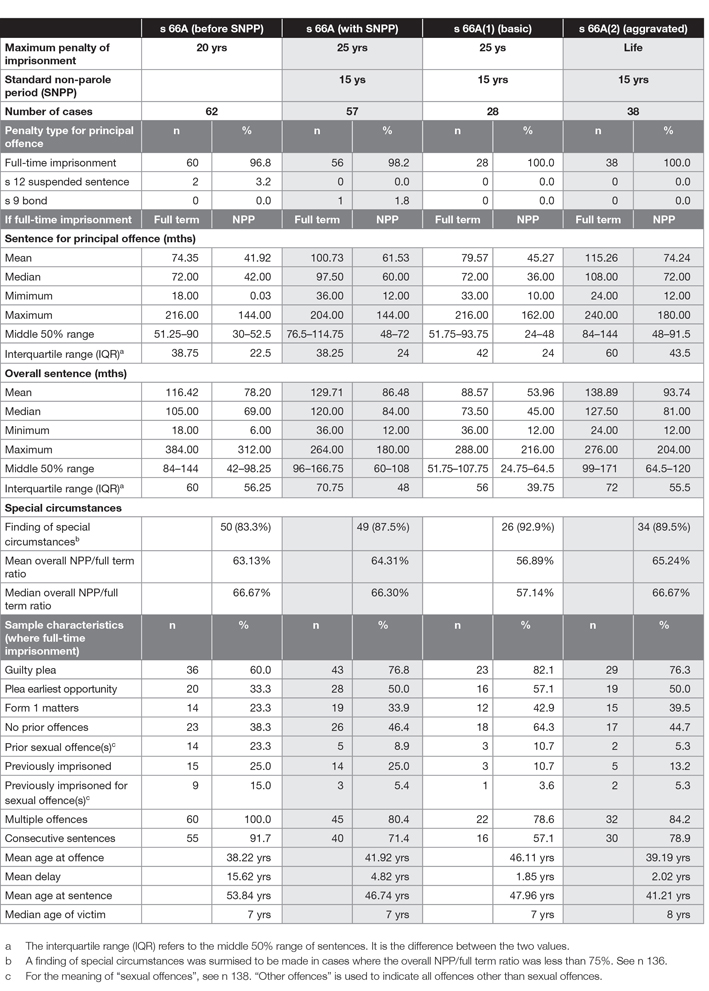

The results of a bivariate analysis of the association between the offender and offence characteristics (sentencing factors) and the full term of sentence are presented in Table 7.

Table 7: Bivariate association between sentencing factors and full term prison sentences (adult offenders)

The bivariate analysis indicated five factors with a statistically significant association with the full term of sentence: the maximum penalty, type of sexual intercourse, victims age, relationship of the offender to the victim and delay. For each of these factors, the median full term:

- increased as the maximum penalty increased169

- was longest where the sexual intercourse was penile/object penetration170

- was longest for victims under 4 years of age171

- was longest for those offences committed by strangers172

- was shortest where delay was more than 20 years.173

As previously mentioned, there was a strong association between delay and offences under s 66A (before SNPP), and hence with the maximum penalty. In respect of delay, no significant difference in the distribution of full term prison sentences was observed when the analysis was restricted to offences in this category.174

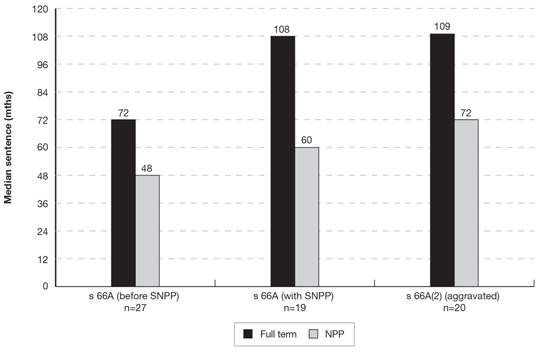

Offences committed by offenders in authority (fathers)

The vast majority (34 or 89.5%) of offenders dealt with under s 66A(2) were in a position of authority and the majority (20 or 58.8%) of these were fathers.

When s 66A(2) was in force, fathers were dealt with under that provision because of the aggravating circumstance that the victim was under their authority.175 Before s 66A(2) commenced, under the common law, a judge was required to sentence fathers on the basis of the aggravating factor of being in a position of authority.176

As discussed (at p 22), one father received a non-custodial sentence following admissions to other offences during participation in a pre-trial diversion program. Analysis of the prison sentences imposed on the remaining fathers dealt with under different sentencing regimes (see Figure 8) revealed significant differences in the distribution of prison sentences for the full term177 and NPP.178

Figure 8: Severity of prison sentences imposed on fathers by particular s 66A offence

The shortest terms were imposed on fathers sentenced for offences under s 66A (before SNPP) when the maximum penalty was 20 years imprisonment:

- median full term: 72 months (range: 18 to 126 months; middle 50% range: 60 to 90 months)

- median NPP: 48 months (range: 9 to 72 months; middle 50% range: 36 to 60 months).

The longest terms were imposed on fathers sentenced for s 66A(2) offences where the maximum penalty is life and the SNPP is 15 years:

- median full term: 109 months (range: 72 to 240 months; middle 50% range: 96 to 141 months)

- median NPP: 72 months (range: 42 to 180 months; middle 50% range: 55 to 100.5 months).

Fathers sentenced for offences under s 66A (with SNPP) where the maximum penalty is 25 years imprisonment and the SNPP is 15 years received:

- median full term: 108 months (range: 48 to 153 months; middle 50% range: 72 to 108 months)

- median NPP: 60 months (range: 24 to 100 months; middle 50% range: 36 to 72 months).

Analysis of sentencing factors (other than the maximum penalty) that may have contributed to the sentence imposed was also undertaken and, with the exception of delay,179 there were no statistically significant differences in the offender and offence characteristics associated with fathers and the offence category under s 66A.

The effect of Muldrock v The Queen

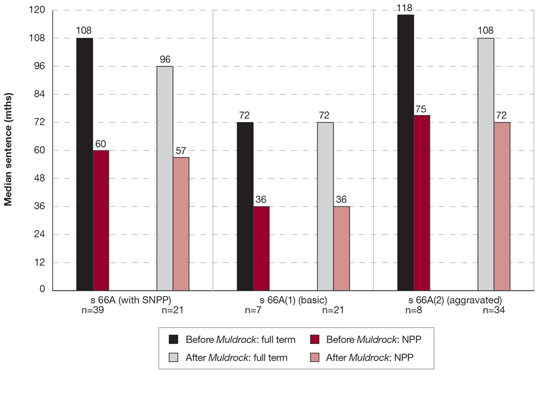

To determine whether Muldrock impacted on sentencing patterns for s 66A offences within the reference period, prison sentences imposed before Muldrock (1 January 2008 to 4 October 2011) were compared with those imposed afterwards (5 October 2011 to 31 December 2014).

Following Muldrock, eight offenders (sentenced before Muldrock) made applications to the Court of Criminal Appeal for leave to appeal out of time. Another offender appealed under Pt 7 of the Crimes (Appeal and Review) Act 2001. Six were allowed on the basis of Muldrock error, one was allowed on another basis and two were dismissed.180

To make meaningful comparisons, the following rules were applied to the nine Muldrock error appeals:

- in the six cases where the appeal was successful because of Muldrock error, the first instance sentence was included in the before-Muldrock period and the sentence following the appeal was included in the period after181

- the case where the appeal was successful on a basis other than Muldrock was included in the before-Muldrock period

- for consistency, the two unsuccessful cases were included in both periods.

Figure 9 shows the severity of prison sentences imposed before and after Muldrock for s 66A offences where the SNPP scheme applied. Notwithstanding the small number of cases in some categories, there was no difference in the median full term or median NPP before or after Muldrock for s 66A(1) basic offences. Although differences were observed in relation to the full term and NPPs for offences under s 66A (with SNPP)182 and s 66A(2),183 these were not statistically significant.

Figure 9: Severity of prison sentences before and after Muldrock by type of s 66A offence

Past and present sentencing patterns

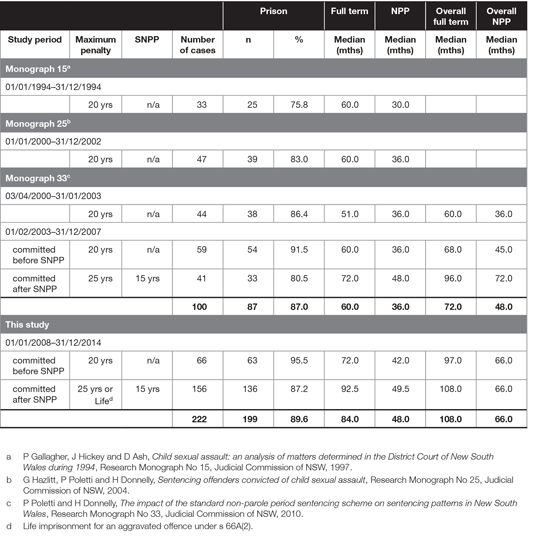

Several Judicial Commission studies have reported sentencing patterns for sexual assault offences, including s 66A offences.184 Unpublished and published data from those studies have been analysed to compare sentencing patterns since 1994.

Table 8 summarises past and present sentencing patterns for s 66A offences covering a period from 1994 to 2014. It does not take account of all the changes affecting sentencing over this period,185 but breaks down the sentences for offences committed before and after the SNPP scheme commenced without distinguishing between offenders excluded from the scheme.186

A high proportion of offenders received prison sentences, ranging from 75.8% in 1994 to 89.6% over this studys reference period. The median full term of sentences has increased by 40% from 60 months in 1994 to 84 months; the median NPP has increased by 60% from 30 to 48 months.

Interestingly, sentences imposed for s 66A offences committed before the SNPP scheme was introduced in 2003 also increased in this studys reference period:

- median full term from 60 months between 1 February 2003 and 31 December 2007 to 72 months

- median NPP from 36 months between 1 February 2003 and 31 December 2007 to 42 months.

Overall sentences also increased:

- between 3 April 2000 and 31 January 2003, the median overall full term and median overall NPP were 60 months and 36 months respectively

- between 1 February 2003 and 31 December 2007, the median overall full term and median overall NPP were 72 months and 48 months respectively

- between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2014, the median overall full term and overall NPP were 108 months and 66 months respectively.

Table 8: Past and present sentencing patterns for s 66A offences

Sentence appeals

Sentence appeals were lodged187 in 63 of 222 cases and 45 were determined by the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal at the time of writing. The 18 cases which are pending have not been included in the following figures. If an offender appealed more than once, the final appeal is counted.188

There were 36 appeals against severity of sentence (80.0%) and nine Crown appeals against inadequacy of sentence (20.0%). Nineteen severity appeals were allowed (52.8%) and 17 were dismissed (47.2%).189 The Crown was successful in eight appeals (88.9%).

There were no sentence appeals with respect to juvenile offenders or offenders sentenced following a special hearing. Appendix B lists the sentence appeals determined by the Court of Criminal Appeal for the cohort of offenders in the study.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Over the 7-year reference period from 2008 to 2014, 222 offenders (of whom 99.1% were male) were sentenced for a s 66A offence. The 222 offenders comprised 188 adults and 34 juveniles. Three adults and one juvenile were convicted following a special hearing. In 83.8% of cases, the offender committed more than one offence. Half (50.5%) were sentenced for multiple s 66A offences.

The mean age of offenders at the time of the offence was 36.9 years but because there was often delay since the offence was committed (mean = 6.9 years) this figure rose to 43.8 years at the time of sentence. The youngest offender at the time of sentence was 14 and the oldest was 86 years.

Just over half of the offenders had no prior record at the time of sentence. However, just over one in 10 (11.7%) had prior convictions for sexual offences including 7.2% who had previously served a prison term for sexual offences. Most offenders pleaded guilty (72.5%); almost half (46.4%) pleaded guilty in the Local Court and just over a quarter (26.1%) entered a plea after arraignment in the District Court.

Over three-quarters of the victims were female (77.0%). The median age of female victims was 7 years and for males it was 8 years. In over 60% of cases the offence was committed by either an immediate (37.8%) or extended (26.6%) family member. Family friends and acquaintances comprised nearly a third of offenders (30.6%). A small proportion of offences were committed in an institutional setting (2.7%) or by strangers (2.3%). Juvenile offenders typically included a brother (32.4%), a family friend (26.5%) or a cousin (14.7%) of the victim. Adult offenders most commonly committed the offence(s) against their biological (22.3%) or non-biological (13.3%) child.

This study analysed sentencing patterns for s 66A offences over the reference period and found that lenient sentence options were rarely used. Non-custodial sentences can be explained to some extent on the basis of an offenders age. Juvenile offenders, in particular, were less likely to be sentenced to full-time imprisonment (39.4%). The prison sentences for juvenile offenders and for offenders sentenced following a special hearing were less severe than for adult offenders. Offenders sentenced following a special hearing and juveniles are not subject to the SNPP scheme (juveniles since 2009).

All except three adult offenders were sentenced to full-time imprisonment (98.1%). While we report median sentences they must be viewed against the background of the litigation that surrounded Muldrock v The Queen190 and the legislative history of the offence. For that reason this study separated data according to four offence categories with different sentencing regimes. This study calculated non-parole periods and full term sentences both at the principal offence and overall sentence level. Bearing in mind the high incidence of multiple offending, the median overall full term sentences for the four offence categories were:

- s 66A(2) (aggravated) offences (committed from 1 January 2009) 127.5 months (range: 24 to 276 months; middle 50% range: 99 to 171 months)

- s 66A(1) (basic) offences (committed from 1 January 2009) 73.5 months (range: 36 to 288 months; middle 50% range: 51.75 to 107.75 months)

- s 66A (with SNPP) offences (committed from 1 February 2003 to 31 December 2008) 120 months (range: 36 to 264 months; middle 50% range: 96 to 166.75 months)

- s 66A (before SNPP) offences (committed from 23 March 1986 to 31 January 2003) 105 months (range: 18 to 384 months; middle 50% range: 84 to 144 months).

These figures must be viewed against the breadth of possible offending and the circumstances of the offender. Seven offenders received an overall sentence of 20 years or longer with a NPP of at least 15 years. The longest overall sentence was 32 years with a NPP of 26 years.191

Generally sentences for s 66A offences have been increasing since 1994. This study shows by reference to previous Judicial Commission publications that since early 2000 the overall full term median sentence has increased from 5 to 9 years.

Following the 2009 repeal and redrafting of s 66A into basic and aggravated forms of the offence, sentences remained high. The relatively lower median sentences for the s 66A(1) basic offence for adult offenders are explicable on the basis that these cases did not have any of the (statutory) aggravating features. The study found the higher rate of non-custodial sentences for juveniles sentenced for s 66A(1) offences was explicable by the relatively high number of cases with a combination of mitigating factors.

It might have been anticipated that sentences involving SNPP offences would decrease following the High Court decision in Muldrock, given the courts conclusion that the SNPP did not have determinative significance. However, the analysis in this study shows that this has not been the case in respect of s 66A offences.

The High Court has repeatedly emphasised that factors relevant to the determination of a particular sentence frequently pull in different directions.192

The maximum penalty of life imprisonment and the SNPP of 15 years are each important guideposts to the appropriate sentence for a s 66A offence. A court has a duty to balance both the objective and subjective factors in determining a sentence that is just in all of the circumstances.193 The weight courts attribute to these factors can vary significantly from case to case. Factors such as the circumstances of the offence, an early guilty plea, the age of the offender and whether or not an offender has a mental illness can have a powerful impact on, for example, the type of penalty imposed and, when imprisonment is imposed, the length of the sentence in a particular case. What remains important is that when sentencing for an offence against s 66A, the court achieves what has been described by the High Court as individualised justice.194

The most recent increase to the maximum penalty of life imprisonment for all s 66A offences enacted by the Crimes Legislation Amendment (Child Sex Offences) Act 2015 is a response to perceived leniency in sentencing for offences involving child sexual assault and to the effect of these offences on the victims.195 That increase may result in higher sentences for those s 66A offences not committed in circumstances of aggravation. Past sentencing patterns suggest sentencing levels for s 66A offences will not decrease in the future.

Appendix A: Sample box plot

Appendix B: Sentence appeals

The sentence appeals listed below were determined by the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal for the cohort of offenders in the study (medium-neutral citation).

Severity appeals

| Dismissed | Allowed |

| AB [2014] NSWCCA 31 | AAT [2011] NSWCCA 17 |

| AH [2015] NSWCCA 51 | AG [2013] NSWCCA 264 |

| Allen [2010] NSWCCA 47a | Eedens [2009] NSWCCA 254 |

| AWKO [2010] NSWCCA 90 | EG [2015] NSWCCA 21 |

| FD [2013] NSWCCA 139 | Essex [2013] NSWCCA 11 |

| HJWG [2011] NSWCCA 50 | GN [2012] NSWCCA 96 |

| IS [2011] NSWCCA 142a | Ingham [2014] NSWCCA 123b |

| JL [2014] NSWCCA 130 | Jolly [2013] NSWCCA 76 |

| JM [2014] NSWCCA 297 | Jones [2012] NSWCCA 262 |

| Kertai [2013] NSWCCA 252 | JRM [2012] NSWCCA 112 |

| NLR [2011] NSWCCA 246 | Kite [2009] NSWCCA 12 |

| NRW [2008] NSWCCA 318 | Leslie [2013] NSWCCA 48 |

| PS [2015] NSWCCA 20 | MD [2015] NSWCCA 37 |

| RJB [2015] NSWCCA 93a | MH [2011] NSWCCA 230 |

| RR [2011] NSWCCA 235 | Muldrock [2012] NSWCCA 108b |

| SW [2013] NSWCCA 255 | PK [2012] NSWCCA 263 |

| TU [2014] NSWCCA 155 | RJT [2012] NSWCCA 280 |

| Simpson [2012] NSWCCA 246 | |

| Smith [2011] NSWCCA 163 |

Crown appeals

| Dismissed | Allowed |

| DKL [2013] NSWCCA 233 | BA [2014] NSWCCA 148 |

| Gavel [2014] NSWCCA 56 | |

| King [2009] NSWCCA 117 | |

| PGM [2008] NSWCCA 172 | |

| RM [2015] NSWCCA 4 | |

| RWB [2010] NSWCCA 147 | |

| SJH [2010] NSWCCA 32 | |

| Woods [2009] NSWCCA 55 |

- The appeal was upheld for offences other than s 66A, see n 189.

- There was more than one appeal, see explanation at n 188.

Endnotes

1 NSW Sentencing Council, Standard non-parole periods: final report, December 2013, see Appendix A: Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW) Part 4 Division 1A: Table Standard non-parole periods, pp 556, Table B20, p 78, and Table B21, p 79 at http://www.sentencingcouncil.justice.nsw.gov.au/Documents/Projects_Complete/snpp%20final%20report.pdf, accessed 11 June 2015; Standard non-parole periods sexual offences against children: interim report, November 2013, see Table B.4, pp 534 athttp://www.sentencingcouncil.justice.nsw.gov.au/Documents/Projects_Complete/SNPP_1/snpp%20sexual%20offences%20interim%20report.pdf, accessed 11 June 2015.

2 Joint Select Committee on Sentencing of Child Sexual Assault Offenders, Every sentence tells a story report on sentencing of child sexual assault offenders, report 1/55 October 2014, at https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/committees/DBAssets/InquiryReport/ReportAcrobat/5741/Final%20Report%20of%20the%20Joint%20Select%20Committee%20on%20Sent.PDF, accessed 11 June 2015. See also the Government Response to the Joint Select Committee on Sentencing of Child Sexual Assault Offenders.

3 Joint Select Committee on Sentencing of Child Sexual Assault Offenders, report 1/55, ibid, recommendation 9, p 55.

4 G Brignell and H Donnelly, Sentencing in NSW: A cross-jurisdictional comparison of full-time imprisonment, Research Monograph No 39, Judicial Commission of NSW, 2015, pp 201.

5 See Table 1 specifically at pp 34.

6 Second Reading Speech, Crimes Legislation Amendment (Child Sex Offences) Bill 2015, Legislative Assembly, Debates, 12 May 2015, p 407:

Child sexual assault is a depraved, cruel and truly awful crime

the community has seen sentences that have not aligned with our sense of right and wrong, our sense of balance. We have seen sentences that have left us questioning whether justice has really been done. We have seen the balance tipped in favour of the offender, not the victim.

In the Joint Select Committee on Sentencing of Child Sexual Assault Offenders, report 1/55, n 2, recommendation 5, p 35, it was recommended that the maximum penalty for an offence against section 66A(1) of the Crimes Act 1900, or consolidated offences or new offences of sexual intercourse with a child under 10, be amended from 25 years imprisonment to life imprisonment. This was to reflect the heinous nature of these offences: at [3.81].

7 Second Reading Speech, Crimes Legislation Amendment (Child Sex Offences) Bill 2015, ibid.

8 (2011) 244 CLR 120.

9 ibid at [32].

10 Elias v The Queen (2013) 248 CLR 483 at [27].

11 The proclamation of commencement was published in GG No 44 of 14 March 1986, p 1160.

12 The Act, and related legislation, was introduced following the 1985 report by the NSW Child Sexual Assault Task Force, which was established in June 1984.

13 Earlier versions of this offence were in s 67 of the Crimes Act 1900 (carnally knowing girl under 10) and s 78H (homosexual intercourse with male under 10). In 1985, both were punishable by life imprisonment but, in 1990, the maximum penalty for s 78H offences was reduced to 25 years: Crimes (Life Sentences) Amendment Act 1989, commenced on 12 January 1990.

14 While s 67 was repealed in 1986 by the Crimes (Child Assault) Amendment Act 1985, the offences in ss 78H and 78I were not repealed until 1 February 2003 by the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Amendment (Standard Minimum Sentencing) Act2002.

15 Second Reading Speech, Crimes (Child Assault) Amendment Bill 1985, Legislative Assembly, Debates, 12 November 1985, p 9325: The new law will also extend the 1981 definition of sexual intercourse to offences against children. This definition includes oral intercourse, which the old carnal knowledge provisions did not include. Oral intercourse fell within the definition of sexual intercourse in s 61A(1), which was amended to apply to, inter alia, s 66A offences.

16 The definition of sexual intercourse is now found in s 61H(1) of the Crimes Act 1900.

17 The relevant proclamation of commencement was published in GG No 263 of 20 December 2002, p 10741.

18 See the discussion concerning the rationale for introducing the standard non-parole period (SNPP) scheme in P Poletti and H Donnelly, The impact of the standard non-parole period sentencing scheme on sentencing patterns in New South Wales, Research Monograph No 33, Judicial Commission of NSW, 2010, pp 34.

19 Second Reading Speech, Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Amendment (Standard Minimum Sentencing) Bill, Legislative Assembly, Debates, 23 October 2002, at p 5818.

20 ibid.

21 (2004) 60 NSWLR 168.

22 The proclamation of commencement was published in GG No 158 of 19 December 2008, p 12303.

23 These amendments reflected a majority of recommendations made by the NSW Sentencing Council in its report, Penalties relating to sexual assault offences in New South Wales, Vol 1, 2008, following its review of the penalties and statutory framework for sexual offences at www.sentencingcouncil.justice.nsw.gov.au/Documents/vol_1_sexual_offences_report.pdf, accessed 12 June 2015.

24 ibid at p 62 [3.60-3.61].

25 Commenced upon date of assent.

26 n 8.

27 n 21.

28 Muldrock v The Queen, n 8, at [32].

29 (2013) 84 NSWLR 328.

30 Achurch v The Queen (2014) 88 ALJR 490 at [37].

31 (2013) 85 NSWLR 783.

32 ibid at [28][30].

33 ibid at [32].

34 (2014) 252 CLR 601.

35 (2014) 252 CLR 621.

36 Kentwell v The Queen, n 34, at [4], [30], [44]; O’Grady v The Queen, ibid at [13].

37 Kentwell v The Queen, ibid at [33][34].

38 Commenced upon date of assent.

39 Second Reading Speech, Crimes Legislation Amendment (Child Sex Offences) Bill 2015, n 6, pp 4078.

40 n 8, at [26].

41 (2005) 228 CLR 357 at [51].

42 R v Dodd (1991) 57 A Crim R 349 at 354.

43 Muldrock v The Queen, n 8, at [27].

44 R v Gavel [2014] NSWCCA 56 at [87][88].

45 Ibbs v The Queen (1987) 163 CLR 447 at 451; Veen v The Queen (No 2) (1988) 164 CLR 465 at 478.

46 R v Moon (2000) 117 A Crim R 497 at [70].

47 Muldrock v The Queen, n 8, at [31].

48 Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (C(SP) Act), s 19(1); Interpretation Act 1987, s 30(1).

49 Second Reading Speech, Crimes Legislation Amendment (Child Sex Offences) Bill 2015, n 6. See also R v Gavel, n 44, at [110][111]; R v King [2009] NSWCCA 117 at [41].

50 n 10.

51 C(SP) Act, s 5(1). Certain alternatives to full-time imprisonment, such as home detention and intensive correction orders, are not available for offenders charged with s 66A offences: ss 66 and 76(b).

52 See analysis at pp 202.

53 n 21; Muldrock v The Queen, n 8, at [22][23], which discussed the approach of the Court of Criminal Appeal in R v Way.

54 See Judicial Commission of NSW, Sentencing Bench Book, 2006, Special Bulletin 2, 19 October 2011, which deals with the substance and possible consequences of the decision in Muldrock v The Queen.

55 n 8, at [27][28].

56 ibid at [26], [32].

57 ibid at [24], [27] and [29], applied in RJA v R [2014] NSWCCA 89 at [23]; AB v R [2013] NSWCCA 273 at [87]; Filippou v R [2013] NSWCCA 92 at [116].

58 Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Amendment (Standard Non-parole Periods) Act 2013 commenced upon assent on 29 October 2013. See Judicial Commission of NSW, Sentencing Bench Book, 2006, Special Bulletin 5, 31 January 2014, which deals with the amendments to ss 54A and 54B of the C(SP) Act.

59 C(SP) Act, s 54A(2).

60 Second Reading Speech, Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Amendment (Standard Non-parole Periods) Bill 2013, Legislative Assembly, Debates, 18 September 2013, p 23736.

61 C(SP) Act, s 54B(6).

62 Early cases such as Fisher v R (1989) 40 A Crim R 442 at 445 remain relevant. See R v ABS [2005] NSWCCA 255 at [26]; Ingham v R [2014] NSWCCA 123 at [38]. See further at p 7.

63 R v BJW (2000) 112 A Crim R 1 at [20].

64 Simpson v R (2012) 227 A Crim R 299 at [71].

65 R v Hudson (unrep, 30/7/98, NSWCCA) at p 3.

66 Ibbs v The Queen, n 45, at 452; R v AJP (2004) 150 A Crim R 575 at [24].

67 R v AJP, ibid; Doe v R [2013] NSWCCA 248 at [54]; Ingham v R, n 62, at [41].

68 Ingham v R, ibid; R v Gavel, n 44, at [97]; Simpson v R [2014] NSWCCA 23 at [33][34]; Doe v R, ibid.

69 Shannon v R [2006] NSWCCA 39 at [37].

70 See Table 1 specifically at pp 34.

71 See the breakdown of the relationships between the victims and the offenders at pp 1819 and the offences committed by offenders in authority (fathers) at pp 278.

72 KJH v R [2006] NSWCCA 189 at [28].

73 MLP v R (2006) 164 A Crim R 93 at [22]; PWB v R (2011) 216 A Crim R 305 at [12].

74 The victim was vulnerable because of his or her age.

75 RJA v R, n 57, at [13].

76 SW v R [2013] NSWCCA 255 at [47].

77 Ingham v R, n 62, at [44].

78 R v AJP, n 66, at [25].

79 JM v R [2014] NSWCCA 297 at [79][80].

80 Jolly v R (2013) 229 A Crim R 198 at [37]; Ingham v R [2011] NSWCCA 88 at [113].

81 Essex v R [2013] NSWCCA 11 at [49][50]; XY v R [2007] NSWCCA 72 at [48].

82 Essex v R, ibid at [44][45].

83 Ingham v R, n 62, at [32]; R v Gavel, n 44, at [100].

84 R v BA [2014] NSWCCA 148 at [33].

85 See Montero v R (2013) 234 A Crim R 532 at [41][55]; Melbom v R [2013] NSWCCA 210 at [42][51]; Ingham v R, n 62, at [11].

86 Ingham v R, ibid at [37].

87 See, generally, Judicial Commission of NSW, Sentencing Bench Book, 2006, at [12-790] Victims and victim impact statements. See also J Cashmore and R Shackel, The long-term effects of child sexual abuse, CFCA Paper No 11, Child Family Community Australia, 2013, at https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/long-term-effects-child-sexual-abuse/introduction, accessed 25 June 2015.

88 DBW v R [2007] NSWCCA 236 at [38].

89 R v King; n 49; Stewart v R [2012] NSWCCA 183 at [61].

90 R v Gavel, n 44, at [107]. Double counting that factor by further applying s 21A(2)(g) of the C(SP) Act is to be avoided: Stewart v R, ibid.

91 R v King, n 49; R v MJR (2002) 54 NSWLR 368 at [57].

92 Attorney Generals Application under s 37 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 No 1 of 2002 (2002) 56 NSWLR 146 at [42].

93 R v JCW (2000) 112 A Crim R 466 at [20][68]; MJL v R [2007] NSWCCA 261 at [15].

94 There may be exceptional circumstances where the need to protect the public renders a plea discount inappropriate: Milat v R [2014] NSWCCA 29 at [73]. See also, R v Borkowski (2009) 195 A Crim R 1, which summarises the relevant principles.

95 Siganto v The Queen (1998) 194 CLR 656 at [35]; R v GWM (2005) 152 A Crim R 482 at [21].

96 R v McNaughton (2006) 66 NSWLR 566 at [20].

97 Veen v The Queen (No 2), n 45, at 477.

98 Ryan v The Queen (2001) 206 CLR 267 at [33].

99 R v PGM (2008) 187 A Crim R 152 at [43], [44].

100 Defined in s 21A(6) of the C(SP) Act to include offences against s 66A.

101 AH v R [2015] NSWCCA 51 at [22], [25].

102 DPP (Cth) v De La Rosa (2010) 79 NSWLR 1 at [178].

103 Muldrock v The Queen, n 8, at [54].

104 ibid at [53].

105 R v Israil [2002] NSWCCA 255 at [26]; R v Henry (1999) 46 NSWLR 346 at [28].

106 R v Israil, ibid at [25].

107 Muldrock v The Queen, n 8, at [54].

108 ibid at [32]; R v Muldrock [2012] NSWCCA 108 at [8], [14]. The sentence was reduced from 9 years (with a non-parole period (NPP) of 6 years, 8 months) to 3 years (with a NPP of 1 year) following remittance from the High Court.

109 Mill v The Queen (1988) 166 CLR 59 at 63; Johnson v The Queen (2004) 78 ALJR 616 at [18].

110 See analysis at p 12.

111 The section was inserted by the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Amendment Act 2010 and relevantly commenced on 14 March 2011 (s 2(1), LW 3 March 2011 (2011175)).

112 See s 66EA(12), the definition of sexual offence, para (a).

113 R v Omar [2015] NSWCCA 67 at [73].

114 R v Moon, n 46, at [35].

115 R v Kay [2004] NSWCCA 130 at [33].

116 R v MJR, n 91, at [31]. MJR has been applied in the context of s 66A cases in AB v R [2014] NSWCCA 31 at [29]; Simpson v R, n 64, at [44] and R v EGC [2005] NSWCCA 392 at [40][41].

117 R v RM [2015] NSWCCA 4 at [130].

118 R v Visconti [1982] 2 NSWLR 104 at 109, 111; Barbaro v The Queen (2014) 88 ALJR 372 at [41].

119 Hili v The Queen (2010) 242 CLR 520 at [18], [48]; Barbaro v The Queen, ibid at [40][41].

120 MLP v R [2014] NSWCCA 183 at [44], [48][51].

121 See R v Gavel, n 44, at [113][118], where the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal said there was no discernible range for sentences imposed for a s 66A(2) offence given its short period of operation.

122 Ingham v R, n 62, at [40].

123 Atai v R [2014] NSWCCA 210 at [14][16]; Imnetu v R [2014] NSWCCA 99 at [34].

124 Complicity and inchoate offences, such as accessories before the fact, aiding and abetting and inciting an offence under s 66A, and attempts under s 66B, are excluded from the analysis.

125 The impact of the standard non-parole period sentencing scheme on sentencing patterns in New South Wales, n 18, p 15.

126 A s 66A offence falls within the definition of a serious childrens indictable offence in s 3(1) of the Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987, which must be dealt with according to law, that is, in the District or Supreme Court: s 17. In practice, these matters are dealt with in the District Court.

127 Where such appeals resulted in an acquittal, new trial or remittal to the lower court, the record was removed from the data. If the appeal resulted in a new sentence, that sentence replaced the first instance penalty. Sentences imposed after a retrial or remittal are included if they fall within the reference period. Outcomes in appeal cases published on Caselaw NSW up to and including 22 May 2015 have been taken into account.

128 No offender was sentenced for further s 66A offences at another court appearance within the reference period, but one offender was sentenced after he disclosed further offences whilst participating in a diversion program (see p 22).